Falcon. Dragon. Starlink. Starship. Starman.

SpaceX has contributed a lot to our spaceflight vernacular, showing just how far the company has come in its first 20 years.

Elon Musk founded SpaceX on March 14, 2002, with big dreams of creating reusable rockets, commercial spacecraft and other advanced technology. Musk has said that few believed it was possible, during an era when space agencies still dominated the industry and space hardware was mostly expendable, save for a few examples like NASA’s space shuttle and its solid rocket boosters.

Now, 20 years later, SpaceX is a dominating force of its own. The company aims to build out its 2,000-satellite-strong Starlink internet constellation to hold perhaps 30,000 spacecraft. It’s ramping up an orbital space tourism program and is the sole U.S. provider for crewed missions to the International Space Station. And as Musk envisioned, SpaceX is now regularly launching and landing rockets while carrying payloads for a wide range of customers, from private companies to NASA and the United States Space Force.

Musk and SpaceX are in the headlines a lot, and the coverage isn’t always positive. In 2018, for example, the billionaire entrepreneur sipped whiskey and took a puff of marijuana during his 2.5-hour live appearance on The Joe Rogan Experience, prompting a NASA safety review of SpaceX practices. That same year, Musk insulted an individual involved in rescuing Thai boys from a flooded cave. The Starlink constellation is causing worries about orbital debris and interference with astronomy observations. And yet Musk persists in being himself, and his company is one of the most powerful in the space industry.

Here are eight ways in which SpaceX rose from relative obscurity to “Saturday Night Live”-level fame.

8) SpaceX made big spaceflight dreams mainstream again

Readers of a certain age may remember German-American rocket scientist Wernher von Braun partnering with entities like Disney to popularize space stations and future crewed space travel in the 1950s, in the years before the Saturn V rocket, whose design he led, launched people to the moon during NASA’s Apollo program.

Such big dreaming rapidly became uncool in the 1970s as Apollo faded into history, NASA’s budget was slashed and the agency’s human spaceflight focus shifted to (supposedly) low-cost missions to low Earth orbit. The space shuttle was a remarkable machine, but it never came through on the low launching costs NASA wanted.

Enter Musk. He had remarkable independence for a spaceflight player, given that he received $180 million in 2002 (roughly $280 million in today’s dollars) when eBay bought Paypal. He poured much of this fortune into starting up SpaceX and from the beginning talked about the need for humans to go interplanetary to reduce the threat of extinction. Mars, he said, would be a great place for us to go.

Musk has said that, around 2002, he began researching NASA’s plans to land people on the Red Planet and couldn’t believe there was no published timeline available. (In more recent years, NASA has suggested the 2030s as a goal.) That’s when Musk says he envisioned a Mars mission “to spur the national will,” Wired reported.

Meanwhile, Musk worked on accumulating reputation and contracts closer to home to launch satellites, International Space Station cargo and people. It took years to demonstrate that the reliability of SpaceX could rival that of big companies such as Arianespace and United Launch Alliance, but (as we’ll talk about below) Musk’s ability to spend a lot of money testing reusable rocket technology helped in that effort.

In latter years, Musk and SpaceX have poured much of their energy into developing Starship, a huge rocket-spaceship duo designed to get people to Mars and other distant destinations.

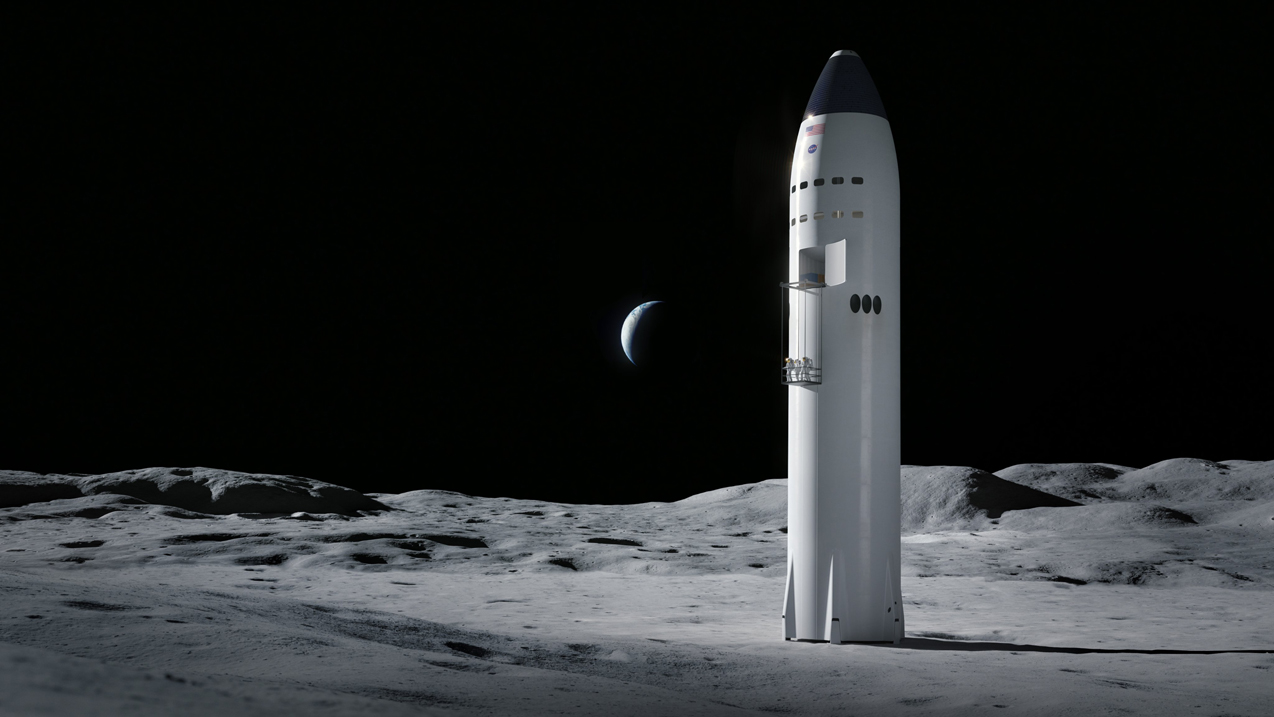

Multiple Starship prototypes went boom during high-altitude test flights, but one finally nailed its landing in May 2021. And NASA picked Starship as the first crewed lander for its Artemis program of lunar exploration, which aims to put boots back on the moon in the middle of this decade.

Starship still has a number of hurdles to clear, however. For example, the system has yet to launch on an orbital test flight; SpaceX is awaiting regulatory approvals before making the first attempt, which could come in the next month or so.

7) Put billionaires front stage of space exploration

Musk isn’t the only billionaire playing a large role in the space industry, of course. Jeff Bezos established the spaceflight company Blue Origin in 2001, for example, and the suborbital space tourism company Virgin Galactic is part of Richard Branson’s Virgin Group.

But Musk has been in the public eye more than his fellow space billionaires, partly because of SpaceX’s many high-profile successes and partly because he’s a very active (and sometimes controversial) Twitter user.

Blue Origin, by contrast, operated in relative secrecy for much of its existence, making few public announcements. (That has changed in recent years, however, as the company has begun flying tourists to suborbital space on its New Shepard vehicle.) Branson is a colorful personality, but Virgin Galactic’s suborbital tourist system isn’t fully up and running; the company has four spaceflights under its belt but has yet to fly a paying customer.

Meanwhile, Musk has regularly provided updates about SpaceX’s various systems on Twitter, given livestreamed Starship progress reports that quickly became must-watches for space fans and inserted himself into the cultural mainstream in a variety of other ways. For instance, he hosted “Saturday Night Live” in 2021, playing the Nintendo supervilllain Wario during his appearance.

Space tourism made a big leap in 2021, with individuals flying to space with SpaceX, Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin. Branson and Bezos themselves flew on their respective company’s systems. Inevitably, given that a seat on Virgin Galactic (for example) now costs $450,000, tremendous wealth is associated with these various opportunities. That means that very wealthy people are the key audience for selling tickets.

There are ethical issues with having the super-rich on spacecraft, to be sure. People have raised questions about what it means to have an industry in which rich people, or people who have received favors from rich people, are the only ones who get to take part. But then there is the example of Inspiration4, which flew to Earth orbit for three days aboard a SpaceX Dragon in September 2021.

Inspiration4 — the first-ever all-private crewed trip to Earth orbit — was funded and commanded by billionaire Jared Isaacman, who (similar to Musk) made his fortune with a payment system, called Shift4. Isaacman opened the other three seats on his spacecraft to regular folks, two of whom won their opportunities through contests, with the third flying on behalf of a charity: St. Jude’s Children Research Hospital in Memphis.

Isaacman wanted to raise millions of dollars for St. Jude, and he achieved that goal, along with a healthy dose of publicity. Isaacman recently announced a set of new private missions with SpaceX, which will be run under the Polaris Program. Isaacman hasn’t yet named the crews for all the opportunities, but has said each of these missions will also be charity-focused.

6) SpaceX made launch webcasts appointment viewing

Numerous space companies today run their own spaceflight broadcasts, but SpaceX’s tend to stand out. Over the years, millions of people have tuned in to the company’s broadcasts to see rocket stages landing on ships at sea and, in one particularly spectacular example, a spacesuit-clad mannequin launching into orbit around the sun.

The mannequin was one of the stars of the debut Falcon Heavy launch in February 2018. The huge rocket lifted off without a hitch, and its three first-stage boosters came back to Earth within view of a huge crowd at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the biggest such group since the space shuttle program ended in 2011.

When the webcast shifted back to an in-space view, the Falcon Heavy’s upper stage had a spectacular reveal: a mannequin astronaut, driving a Tesla Roadster. SpaceX began playing David Bowie’s “Starman” on the broadcast, dubbing the mannequin with the same name as it began a road trip around the sun.

The “astronaut” caught tremendous international attention; this reporter received a message about it from an individual in Mariupol, Ukraine, who didn’t usually follow spaceflight, for example. But it’s just a singular example of what the webcasts have offered to long-time SpaceX fans.

SpaceX has been strategic in offering camera views of staging, high-definition glimpses of its rockets during launches and at-sea landings, and numerous statistics that fans enjoy parsing on channels such as Twitter and Reddit.

In a sense, the company is borrowing from the earliest days of NASA, when the agency was running open television broadcasts during an era when crewed rocket reliability was far less than what is possible today. NASA and SpaceX, in fact, tend to have competing broadcasts during joint launch efforts of the Crew Dragon system, which creates a considerable (but fun) challenge as space fans split their attention among their social media channels and livestreams.

5) SpaceX brought new style to spaceflight

In 2017, Musk revealed the long-awaited spacesuits that NASA astronauts and others aboard his spaceships would don during future flights. True to his tradition of breaking news on social media, he posted the first images on Instagram (although the link doesn’t work today.)

While Musk noted that it was “incredibly hard” to balance aesthetics and function in the spacesuits, right away people began commenting on its movie-star look. The SpaceX suit was so thin, in fact, that Musk had to reassure his Instagram followers: “It definitely works. You can just jump in a vacuum chamber with it, and it’s fine.”

The design was no Hollywood coincidence; it came from legendary costume designer Jose Fernandez, who created outfits for blockbusters such as “Wonder Woman,” “Wolverine,” “Batman vs. Superman” and “Captain America: Civil War.”

SpaceX picked flashy opportunities to test its spacesuit in space, along with the usual pressure tests and vacuum chamber tests. One flew with Starman on the Falcon Heavy rocket in 2018, and another was used on the dummy Ripley that flew aboard the uncrewed SpaceX Crew Dragon Demo-1 test flight to the ISS in 2019.

There also are the sleek controls for Crew Dragon, which features touchscreens instead of dials and switches. The Crew Dragon console offered interesting experiences for NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley, who were used to the space shuttle’s controls (parts of which date from the 1970s, although much was updated as the program evolved.)

“As a pilot, my whole career having a certain way to control a vehicle, this is certainly different,” Hurley said during a news conference in May 2020. “But we went into it with a very open mind.”

4) SpaceX ramped up orbital space tourism

We’ve already spoken about Inspiration4’s mandate, but other aspects of the orbital space tourism mission are worth mentioning. The Crew Dragon Resilience and its spaceflyers circled Earth for three days at an altitude higher than any human has achieved since a Hubble Space Telescope servicing mission in 1999.

At 367 miles (590 kilometers) above our planet, Inspiration4 experienced a much higher view than astronauts receive on the ISS (about 250 miles, or 400 km). The crew also had the advantage of a domed window, rather than the little portholes that previous generations of NASA and Soviet astronauts had in the 1960s and 1970s.

SpaceX’s marketing efforts for space tourism also extend to the dearMoon project, for which Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa is seeking eight crew members to join him on a trip around the moon using SpaceX’s Starship spacecraft. The project received some early negative press, as Maezawa asked for a girlfriend to come with him, but a swift marketing shift had Maezawa instead asking for “people from all kinds of backgrounds to join.” The targeted launch date is 2023.

In the nearer term, SpaceX will fly paying customers to the International Space Station for Houston-based company Axiom Space, which has booked several missions using the Falcon 9-Dragon system. The first of those flights, Ax-1, is scheduled to launch on March 30.

And Isaacman’s Polaris Project is providing a unique opportunity for SpaceX to show its stuff in orbital spaceflight. The first mission with four private astronauts will include two individuals from SpaceX highly experienced in crewed and uncrewed missions: Sarah Gillis and Anna Menon, who assist in matters ranging from crewed spaceflight development to taking the helm in SpaceX’s Mission Control.

It’s too early to say yet how SpaceX will position the marketing of its own personnel flying on space missions, but this may be done with some flare given how SpaceX showcased Starman. That said, SpaceX allowed Isaacman to take the lead in promoting Inspiration4, so it may be part of the arrangement to allow Isaacman to handle the work again for Polaris.

3) SpaceX returned crewed orbital spaceflight to U.S.

When NASA retired its space shuttle fleet in 2011, the agency was in the midst of supporting several American space companies working to develop the vehicles’ replacement, including SpaceX. SpaceX and Boeing won out in 2014, splitting NASA’s $6.8 billion Commercial Crew Transportation Capability award.

At award time, NASA hoped to have SpaceX’s Crew Dragon and Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner capsule flying by 2017, but technical and funding issues pushed the timeline back by several years. In May 2020, SpaceX launched its historic Demo-2 test mission, which sent a Crew Dragon carrying Behnken and Hurley to the International Space Station as the world was in the grips of the coronavirus pandemic, providing some hope and excitement for a captive audience looking for such things.

It was the first crewed orbital liftoff from American soil in nine years, although Florida could not see the usual launch crowds due to safety protocols associated with the pandemic. Still, the livestreams from NASA and SpaceX showed the spacecraft flawlessly sending Behnken and Hurley to the International Space Station for a two-month stay.

The splashdown on Aug. 2, 2020, the United States’ first crewed one since the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975, also went technically well. Unfortunately, however, the area was swarmed by boaters eager to see the procedures up close. (NASA and SpaceX have since changed their protocols to advertise less specifically where the splashdown will occur.)

SpaceX has since run several operational crewed flights to the ISS with few issues, in contrast to Boeing’s Starliner. Starliner ran into numerous snags during its uncrewed test flight to the orbiting lab in late 2019 and hasn’t had the chance yet to return to space for another try. Numerous issues, including launch windows, the pandemic and technical concerns, mean Starliner likely won’t launch until at least May 2022. Crewed flights may not follow until 2023 or so.

This means that for now, Crew Dragon is the only option for NASA astronauts (or space tourists) to leave for orbital space from American soil.

After the space shuttle retired and before Demo-2 lifted off, NASA was completely dependent on Russian Soyuz vehicles to take its astronauts to and from the space station. Relations between NASA and Russia have been rocky in recent weeks after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, prompting numerous international sanctions. ISS operations are normal for the time being, but NASA doubtless is breathing a sigh of relief that an American crewed orbital capability is up and running in case, as the relationship with Russia could well deteriorate further.

SpaceX may also be able to replace some Russian services to the ISS, such as reboosting the orbiting complex periodically to avoid drag from Earth’s atmosphere pulling the station back to the planet. (Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus cargo spacecraft will also test out this capability during its current mission to the ISS, which began in February.)

2) SpaceX helped reduce launch costs

Reusable rocket and spacecraft technology is the backbone upon which SpaceX builds its cost estimates, which tend to be lower than those of its competitors.

For example, the per-seat cost for SpaceX’s Crew Dragon is around $55 million, NASA’s Office of the Inspector General said in 2019, which is roughly 60% less than both Boeing Starliner (projected at $90 million) and the Russian Soyuz (then $85 million).

For further perspective, SpaceX sells Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launches for $62 million and $90 million, respectively, well below the prices of their chief competitors. In late 2020, for example, it cost a little more than $100 million to book a ride on United Launch Alliance’s workhorse Atlas V rocket. (The Atlas V is not quite as powerful as the Falcon 9.)

Launch customers also pay varying amounts for getting aboard Falcon 9 or Falcon Heavy depending on the size of their satellite, in line with industry practice. So a fleet of tiny cubesats from different organizations, as an example, may typically pay lower costs for their “rideshare” than the operator of the main satellite that is also atop a Falcon 9 on the same launch.

Low costs may extend to future systems, too. The super-heavy Starship system, for instance, is projected to use only $900,000 worth of propellant to make it to Earth orbit. Operational costs overall could be as low as $2 million per flight, Musk suggested in 2019. If that’s the case, Starship will be truly revolutionary, slashing the cost of access to space like never before.

The caveat with all these costings as that some are theoretical and others may be subject to change with recent supply issues induced by the pandemic. But overall, SpaceX is still pointed to as an example of reliably allowing lower-cost launches than its competition.

1) SpaceX is reusing rockets and landing boosters

In a stunning bit of rocket tech now considered routine, SpaceX recovers and reuses the first stages of both Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets. Indeed, such reuse is key to the company’s ability to keep costs down.

The returning boosters come to the ground for soft vertical landings about nine minutes after liftoff, either on solid ground near the launch pad or on autonomous “drone ships” mid-ocean.

The company realized its 100th rocket landing in December 2021, six years after notching its first successful touchdown on an orbital mission. SpaceX also seeks to launch frequently, especially with regard to getting its Starlink constellation operational, and stresses that reusable rockets are key to boosting launch cadence as well as lowering costs.

At the moment, Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets are only partially reusable; their upper stages are still discarded after launch. The Starship-Super Heavy system, however, will be fully reusable. And the Super Heavy landings will be quite a sight to see.

“We’re going to try to catch the Super Heavy booster with the launch tower arm, using the grid fins to take the load,” Musk said via Twitter on Dec. 30, 2021..

Yes: SpaceX plans to bring the giant Super Heavy back to Earth directly on the launch tower. While Musk has talked about this idea before, the new tweak adds some interesting design challenges. In fact, when you think about it, Super Heavy won’t actually be touching down, as it will be caught midair by the tower arm.

What this change would mean is that Super Heavy wouldn’t need landing legs. Musk also listed additional benefits to this strategy: “Saves mass and cost of legs and enables immediate repositioning of booster onto launch mount — ready to refly in under an hour,” he said in another Dec. 30 tweet.

Reusability is the key breakthrough needed to make the settlement of Mars economically feasible, Musk has repeatedly stressed. He recently estimated that SpaceX could get people on the Red Planet’s surface by 2026, if Starship development and testing go well. While the timeline is optimistic, his goal to put boots on Mars has not changed in decades and continues to fuel the work that SpaceX does.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.