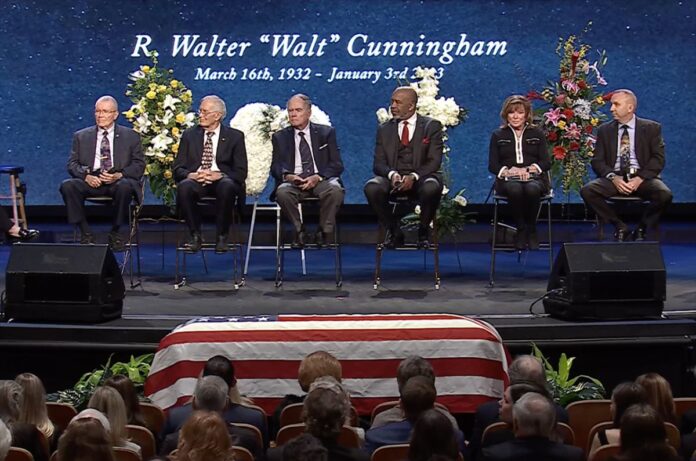

Judging just by the astronauts who came together to remember Walt Cunningham on Tuesday (Jan. 24), the late Apollo 7 pilot’s reach extended far beyond his 1968 launch into space.

The group, who took part in a panel discussion (opens in new tab) before a more traditional funeral service at Houston First Baptist Church, included two of Cunningham’s fellow Apollo colleagues and four NASA veterans who flew on the space shuttle and International Space Station — the latter well after Cunningham had retired. All of them said they were grateful for Cunningham’ friendship.

“Fred and I were in the same group of what we called the ‘Original 19,’ and of course we met all the astronauts when we first arrived and Walt was one of them,” said Apollo 16 moonwalker Charlie Duke, who with Apollo 13 lunar module pilot Fred Haise, joined NASA’s astronaut corps in 1966, two years before Cunningham made his first and only flight.

“He was a great friend, a great mentor and great spokesman for NASA throughout the years. We really miss him,” said Duke.

Related: Walter Cunningham: Apollo 7 astronaut

Cunningham died on Jan. 3 (opens in new tab) due to complications from a fall. He was 90.

The Apollo 7 mission made history in a number of ways. It was the first U.S. spaceflight to broadcast live television from space and it was the first time NASA launched a three-person crew (Cunningham’s crewmates, Wally Schirra and Donn Eisele, preceded him in death). Most importantly, though, the “101-percent successful” mission (opens in new tab) served as a critical shakeout cruise for the Apollo command module, which was redesigned after a fire claimed the lives of the Apollo 1 crew during a test on the launchpad.

“The first flight of a new spacecraft (opens in new tab) is always a critical mission,” said George Abbey, who as an engineer and then director, helped lead NASA’s efforts to land astronauts on the moon. “If you look at the contribution that Walt and his teammates made on Apollo 7, it was really the key to allowing us to make the lunar landing that we made in July of 1969. It wouldn’t have occurred without the success of that mission.”

“I will always have memories of Walt and his crew flying that flight,” said Abbey.

Bob Crippen did not fly into space until the first launch of the space shuttle in 1981, but having transferred to NASA from the U.S. Air Force’s cancelled Manned Orbiting Laboratory program in 1969, he worked with Cunningham on the Apollo Applications Program (AAP), which evolved into the Skylab orbital workshop.

One of the first tasks that Cunningham assigned Crippen to do was test the waste collection system for the new space station.

“They want to do [the test] on a zero-g parabola on the KC-135 [aircraft] at Wright Patterson Air Force Base. Your task is to go deliver a ‘number two’ in one parabola, which is about 30 seconds,” Crippen recalled Cunningham telling him. “Being the new guy you don’t turn down a job and so I said, ‘Aye, aye sir’ and went to Dayton, Ohio.”

“That morning, I got up and had a big breakfast of steak and eggs, and I delivered on the first parabola. I was happy to come home and tell Walt, ‘mission accomplished,'” he said with a big smile.

“I am told that Walt wanted this to be fun and to laugh,” journalist Melissa Jacobs, who moderated the panel, said.

The three other members of the panel became astronauts after Cunningham had left NASA to become a businessman.

“I first met Walt when I was in middle school,” said Bernard Harris, who in 1995 became the first Black astronaut to perform a spacewalk on the second of his two space shuttle flights. “It wasn’t until probably 20 or 30 years later that I actually got to know Walt.”

“When I got out [of NASA] and decided I was going to go into venture capital, I [thought] I could be the first [astronaut] to [do so]. Well, it turns out I wasn’t. Walt started his venture capital firm in 1982. He then became my mentor. So I owe him a lot.”

Anna Fisher was one of the first six women to become a NASA astronaut and was the first mother to fly into space. Like Harris, she got to know Cunningham long after they had both left the program.

“I wish I had a chance to work with him,” she said. “He sounds like he would have been a great boss, but I’m glad that it was better late than never to have a friendship with this amazing, very opinionated person, who I really truly admired.”

As the only astronaut on the panel still on active flight duty with NASA, Randy Bresnik only got to know Cunningham relatively recently, but drew parallels in what Cunningham achieved with what the space agency is doing now.

“I like to think that Walt’s spirit certainly lives on as we just had Artemis 1, the first uncrewed flight of the Artemis program. The very next flight, ideally in two years from now, we’re going to put people on, just like we did with Apollo 7,” said Bresnik. “And we’re not just keeping them in low Earth orbit, we’re sending them to the moon and back. All of that would not be possible without pioneers like Walt.”

“So Godspeed Walt Cunningham,” he said.

Follow collectSPACE.com (opens in new tab) on Facebook (opens in new tab) and on Twitter at @collectSPACE (opens in new tab). Copyright 2023 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.