HOUSTON — While witnessing the Apollo 11 launch and moon landing in July 1969, Life Magazine journalist Norman Mailer was so befuddled by events that he renamed himself in his writings.

On Monday (April 3), I sympathized with Mailer’s choice to call himself Aquarius. I, a Canadian journalist, had the good fortune to attend the ceremony at which NASA announced the crewmembers for its Artemis 2 around-the-moon mission. One of those astronauts, Jeremy Hansen, is a Canadian, and seeing him introduced left me a bit unmoored.

When Apollo 11 soared moonbound into the skies on July 16, 1969, there wasn’t even a Canadian astronaut program. The robotic Canadarm technology that garnered Canadians seats on NASA space shuttle missions (and beyond) was in its infancy. And Jeremy Hansen wouldn’t even be born for nearly seven more years.

Related: NASA’s Artemis program: Everything you need to know

And the world has changed a great deal just since 2009, when Hansen and colleague David Saint-Jacques were announced as astronaut candidates by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). (Other Canadian astronauts have flown to space with NASA or by other means, but here I’m focusing on the CSA ones.)

I still recall Hansen and Saint-Jacques being completely surrounded by cameras, mics and bright lights seconds after the reporters were unleashed on them. Realizing that fighting for meaningful quotes was futile, I instead sprinted to a nearby library to file that story. Today, with a smartphone, I can type these words out comfortably in between press events.

It’s been an especially interesting ride for Hansen since then. He came into the retiring space shuttle program and helped support CSA astronaut Chris Hadfield’s journey to space in 2012-2013. No Canadian then flew for six years due to our minority position in the International Space Station (ISS). (Our robotics work is mighty indeed but brings few flight dates at just 2.3% of ISS contributions.)

While Saint-Jacques got the nod to fly in 2018-2019, Hansen picked up a significant ground responsibility: nurturing the 2017 astronaut class training schedules for two years, making him the first-ever Canadian to lead a new NASA group. He remained busy with training and mission support, but his wait so far is expected to last an impressive 15 years, assuming Artemis 2 lifts off in late 2024 as currently planned.

Related: Canada joins NASA’s Lunar Gateway station project with ‘Canadarm3’ robotic arm

(opens in new tab)

‘By an uncertain moon with its grudging light’

As much as I love Mailer’s writing, prominent parts of “Of A Fire On The Moon” (Little, Brown, and Co., 1970) are deeply misogynistic and racist. One restless night last month, in the hours after I learned I’d be going to Houston to cover the Artemis 2 crew announcement, I cast about for better cultural ground.

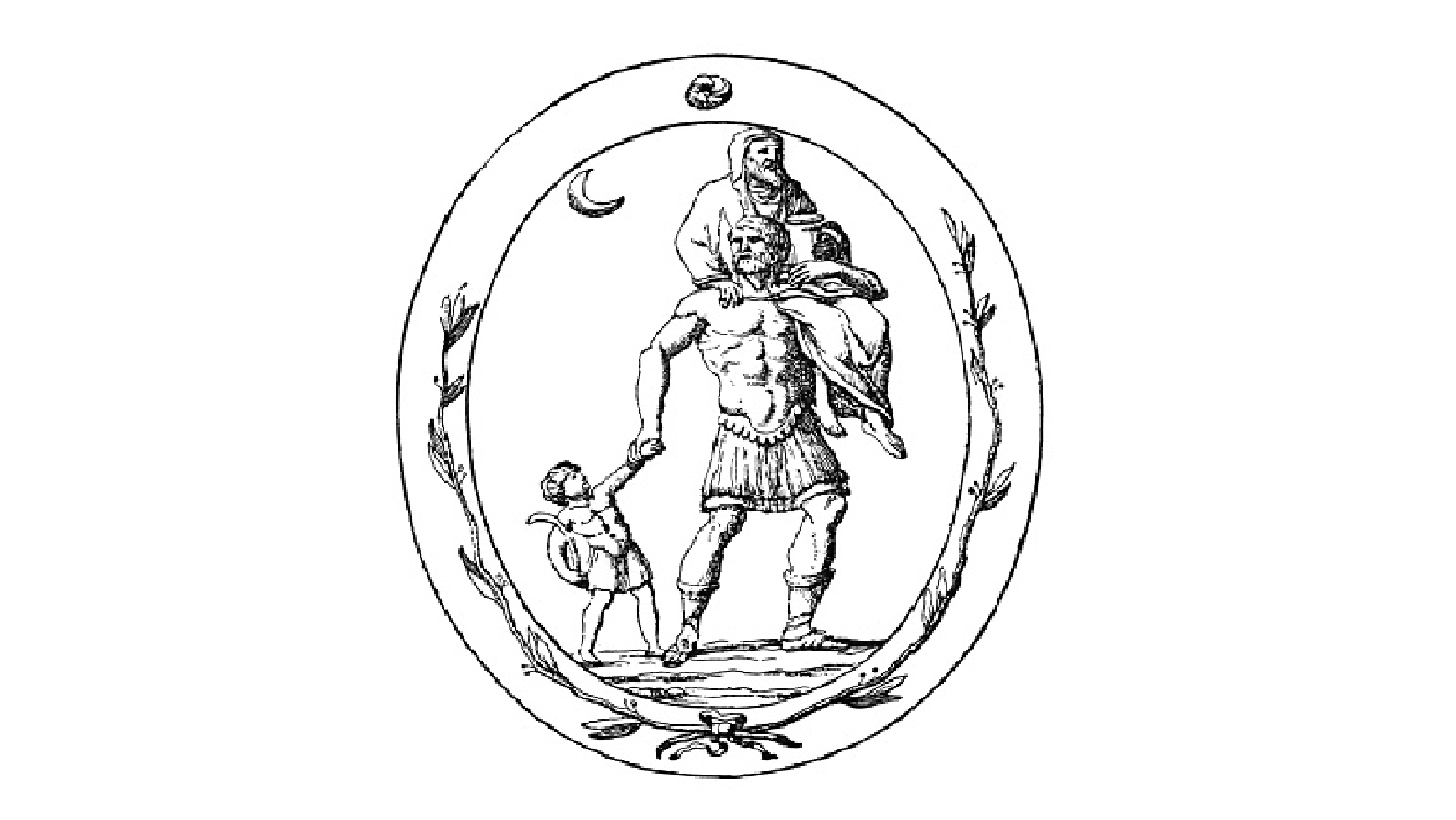

My scattered internet searches reminded me of the 1911 poem “Ithaka (opens in new tab),” by Constantine P. Cavafy, which describes the acquisition of wisdom by analogy of a Homeric journey: “Laistrygonians, Cyclops, wild Poseidon — you won’t encounter them unless you bring them along inside your soul,” a translated version reassured me.

The following morning, remembering that NASA’s Artemis program is named after a Greek deity, I made a query that led me to Amanda Wilcox, chair of the classics department at Williams College in Massachusetts.

Related: The immortals behind the stars (op-ed)

(opens in new tab)

Artemis is the goddess of the hunt, along with being the goddess of the moon, and transitions accompany her. She is associated with an ancient ceremony for adolescent girls just before they become brides, for example. In terms of voyages, Wilcox noted, Artemis and her twin brother Apollo were born to Leto after a strange journey.

The twins’ father was Zeus, and Zeus’ wife Hera was angry at Leto and refused her shelter. Leto eventually found refuge on the island of Delos, which in Greek tradition remained a wandering land until Leto grasped on to a palm tree and gave birth.

“I don’t know what to make of that in terms of the moon being somewhere we can go to [with Artemis 2], but wandering and then fixity seems really interesting to me,” Wilcox told Space.com.

I also asked about the sense of the liminal that the moon gives us, as it seems close enough to touch from the ground and yet is literally out of this world to us. It also seems changeless, aside from meteor strikes and occasional “moonquakes.”

There are some lunar myths that allude to cultural boundaries and transgressions, Wilcox answered. Endymion, the lover of the moon, was so beautiful that Zeus gave him an eternal reward: to be deathless and ageless. The price of the reward, however, is that Endymion must be eternally asleep.

Other tellings of the myth have a twist: Zeus may have punished Endymion with sleep since Endymion was also in love with Hera — who is, of course, Zeus’ wife.

Related: ‘Moon Knight’s’ Khonshu and 9 more lunar gods and goddesses from around the world

(opens in new tab)

In the Roman sphere, uncertainty also can preside for moon tales. Wilcox was recently teaching a passage in Latin about Aeneas’ descent to the underworld in Virgil’s “Aeneid;” that epic first-century poem is a foundational part of Roman culture attempting to justify its empire-building.

“There’s a beautiful simile that compares the light, as he [Aeneas] descends towards Hades, ‘When but by an uncertain moon with its grudging light,'” Wilcox said, referring to a passage you can see in Latin here (opens in new tab) on the Perseus Project. The moon, she added, was an excellent wayfinding tool for the ancients in a world with no artificial light beyond torches or similar devices.

The moon also may have been a spot where at least some ancients perceived different rules, like the satirical “A True Story” by the second-century Syrian author Lucian of Samosata, whose work survives in ancient Greek despite experts suggesting he preferred Aramaic. The fictional moon voyage brings readers to a “kind of topsy-turvy land” with different rules, such as no women being present at all, Wilcox said.

Her remarks made me think about just how much has changed in our society in just the past 50 years, with advances in diversity along with acknowledgment of how we can still do better.

18,861 days

It’s been a gap of 18,861 days — nearly 52 years — since any moon crew was named at all. Apollo 17’s astronaut trio was announced (opens in new tab) on Aug. 13, 1971, more than a decade before Canadian astronauts even existed. It’s therefore still a shock to me that U.S. President Joe Biden last week talked about Artemis 2 and Canada’s moon astronaut at a space museum just a few minutes’ drive from me, in Ottawa.

My mentors included two Canadian journalists (Lydia Dotto and Peter Calamai) who were young and enthusiastically working on moon mission coverage in the Apollo era and have since passed away; that’s how long half a century is.

Society has also changed greatly, which is why NASA has promised to take women and people of color to the moon on its Artemis missions. Moreover, the agency is also acknowledging history in other ways.

Related: How NASA’s Artemis moon landing with astronauts works

(opens in new tab)

For example, NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in coastal Florida has noted that it sits upon historical territory of the Ais and Timucuan peoples (opens in new tab). The agency also has talked about the enslaved peoples who worked upon the Elliot Sugar Plantation (opens in new tab), whose ruins lie within KSC grounds, some 250 years ago.

In 2022, NASA astronaut Jessica Watkins completed the first long-duration mission by a Black woman. Her colleague Nicole Mann touched down just weeks ago after becoming the first Native American woman in space. (Mann is a member of the Wailacki of the Round Valley Indian Tribes in northern California.)

So, progress has been made recently. But we must remember cultural issues of the early space program. For example, Wernher von Braun, a pioneering rocketeer with key roles in the Apollo program, was previously a rocket engineer for Nazi Germany. Former NASA Administrator James Webb, although officially cleared of direct wrongdoing concerning LGBTQ+ employees, recalls for many individuals an era when folks on the gender spectrum were persecuted for being themselves. (Yes, that still happens today, too.)

This was the environment in which the Apollo program was built, an environment in which the Hidden Figures or the Mercury 13 didn’t have a chance of flying or acknowledgement. While we have done much to recognize these individuals since, even today, the space industry still grapples with sexual harassment issues and other problems. But just days ago, NASA named two champions for equity and diversity (opens in new tab) to help address ongoing agency needs.

Related: International Women’s Day: Female astronauts keep making strides off Earth

(opens in new tab)

I say all this not to condemn the space program — I adore it, and I am thrilled at how we are trying to get better at including others. For myself, I saw the movie “Apollo 13” in 1996 as a young teenager and began a lifelong obsession with space exploration that keeps me going. Two ginormous posters from the film still adorn my office wall. So believe me, if there was a spot to safely cram another Canadian somewhere in Artemis 2’s Orion spacecraft, I’d be riding along.

In recent weeks, thinking of this Houston opportunity, I’ve been lying awake at night thinking about privilege and luck. It was a different world even for Canadian journalists during the Apollo years. Far fewer women participated, for example. Dotto once told me about the reaction of the all-male crew aboard a recovery ship awaiting the return of Skylab 4 in 1974; the sailors told her they were worried that, as a woman on board, she would somehow bring bad luck to their efforts.

I’m not a perfect person, but I’ve been battling to include space in my coverage all the way back to my student newspaper days in the early 2000s, when few reporters around me seemed to be paying attention to the final frontier. Graduating into a journalism industry in severe recession by 2008 was not my best idea. But I’m stubborn and lucky.

After 20 years of journalism adventures, mostly as a freelancer, I somehow touched down here as a full-time Space.com staffer merely nine months ago. I’m not sure I’ll ever process the near-perfect timing of witnessing the Artemis 2 announcement this week to see a fellow Canadian named to a moon mission.

“Keep Ithaka always in your mind,” Cavafy’s poem reads. “Arriving there is what you’re destined for. But don’t hurry the journey at all. Better if it lasts for years.”

If I may make one wish as I continue this journey, it is that more of us can come along to share in space adventures. I’ll do my best to help with that.

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of “Why Am I Taller (opens in new tab)?” (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or Facebook (opens in new tab).