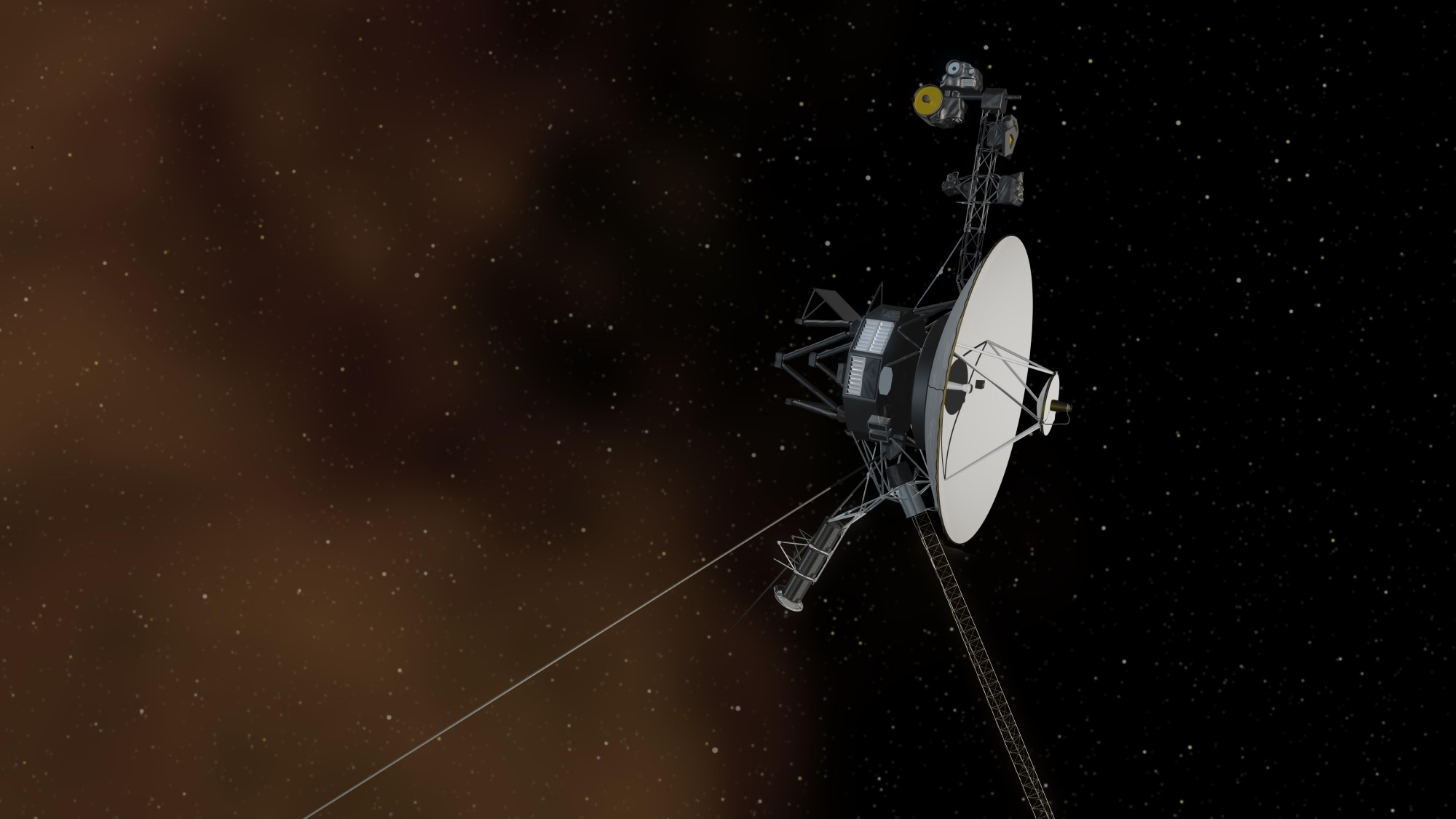

Forty-five years ago, on Aug. 20, 1977, NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on a Titan III-Centaur rocket, embarking on a “grand tour” of the solar system that would include visits to the Jupiter and Saturn systems and would make it the first spacecraft to visit the ice giants Uranus and Neptune and their moons.

Voyager 2 is now 12.1 billion miles (19.5 billion kilometers) away and still sending back data on the distant and unknown heliopause, and scientists are beginning to wonder how long the iconic space probe can keep going.

Designed to take advantage of a once-every-176-years alignment in the 1970s that made it possible for spacecraft to take gravity-assist slingshots from planet to planet across the solar system, the Voyager mission consisted of two probes. Voyager 2 was the first to launch, with Voyager 1 following two weeks later. Both carried the famous “Golden Record,” a 12-inch gold-plated copper disc containing sounds and images portraying the diversity of life and culture on Earth.

Now over 14.5 billion miles (23.3 billion km) away, Voyager 1 is the farthest artificial object from Earth. But Voyager 2 is arguably more iconic because of its incredible multidecade tour of the giant planets.

Related: Celebrate 45 years of Voyager with these amazing images of our solar system (gallery)

Voyager’s “grand tour”

Though it launched second, Voyager 1 was so called because it was to reach Jupiter and Saturn first — in March 1979 and November 1980, respectively — before exiting the plane of the planets where it took the famous “Pale Blue Dot” photo. Voyager 2 visited four planets: Jupiter in July 1979, Saturn in August 1981, Uranus in January 1986 and Neptune in August 1989.

“Both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 provided tremendous legacies for planetary exploration,” Jonathan Lunine, a planetary scientist and physicist at Cornell University who is working on the Juno, Europa Clipper and James Webb Space Telescope missions, told Space.com. “Not only in what they accomplished in terms of science, but also demonstrating that it was really possible to explore the outer solar system with a couple of spacecraft.”

What did the Voyager probes reveal?

Voyager’s discoveries are the stuff of legend among planetary scientists, many of whom still rely on the unique images from the spacecraft’s wide-angle and narrow-angle cameras. The probes spotted volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io, discovered that Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is an Earth-size storm and found that the gas giant has faint rings. They studied Saturn’s rings; saw the giant moon Titan’s thick, Earth-like atmosphere; and revealed the tiny moon Enceladus to be geologically active.

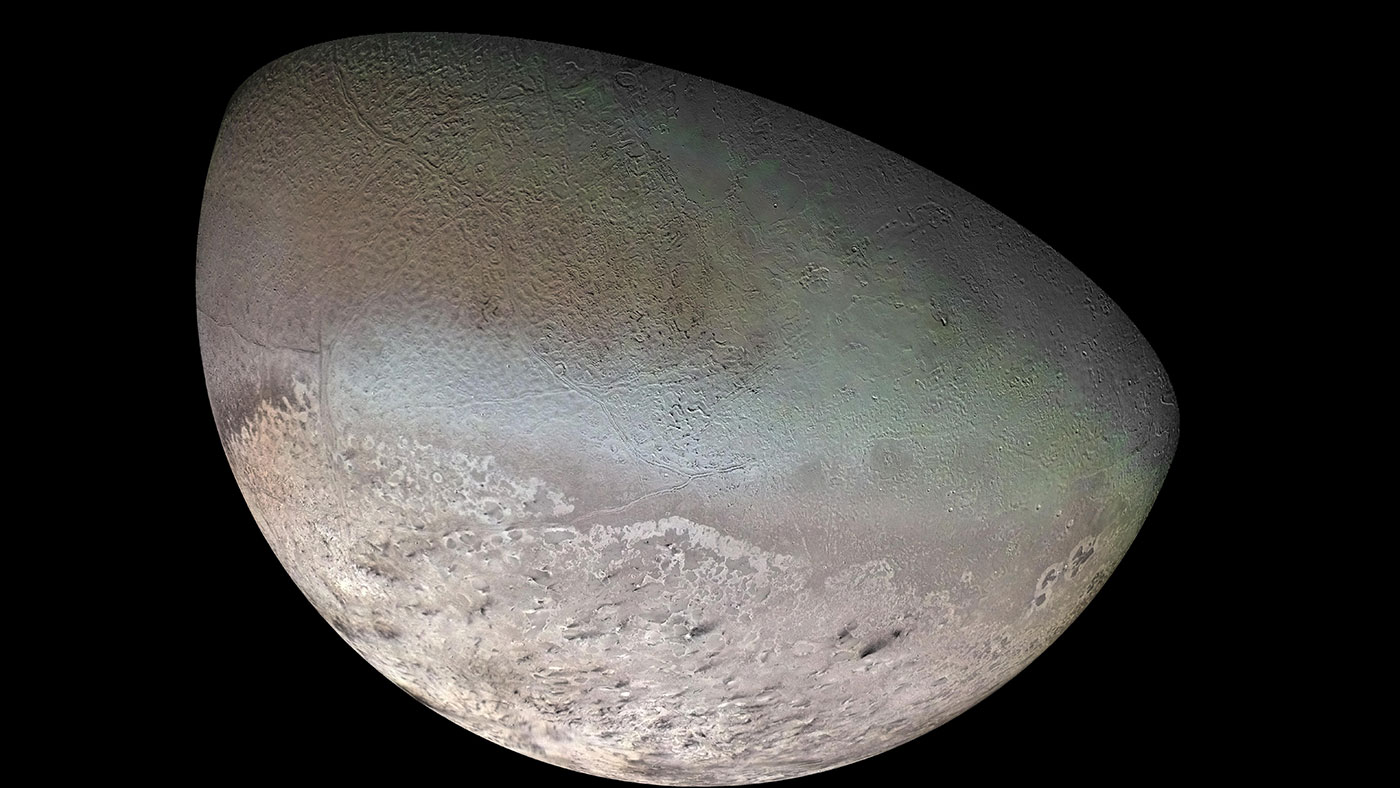

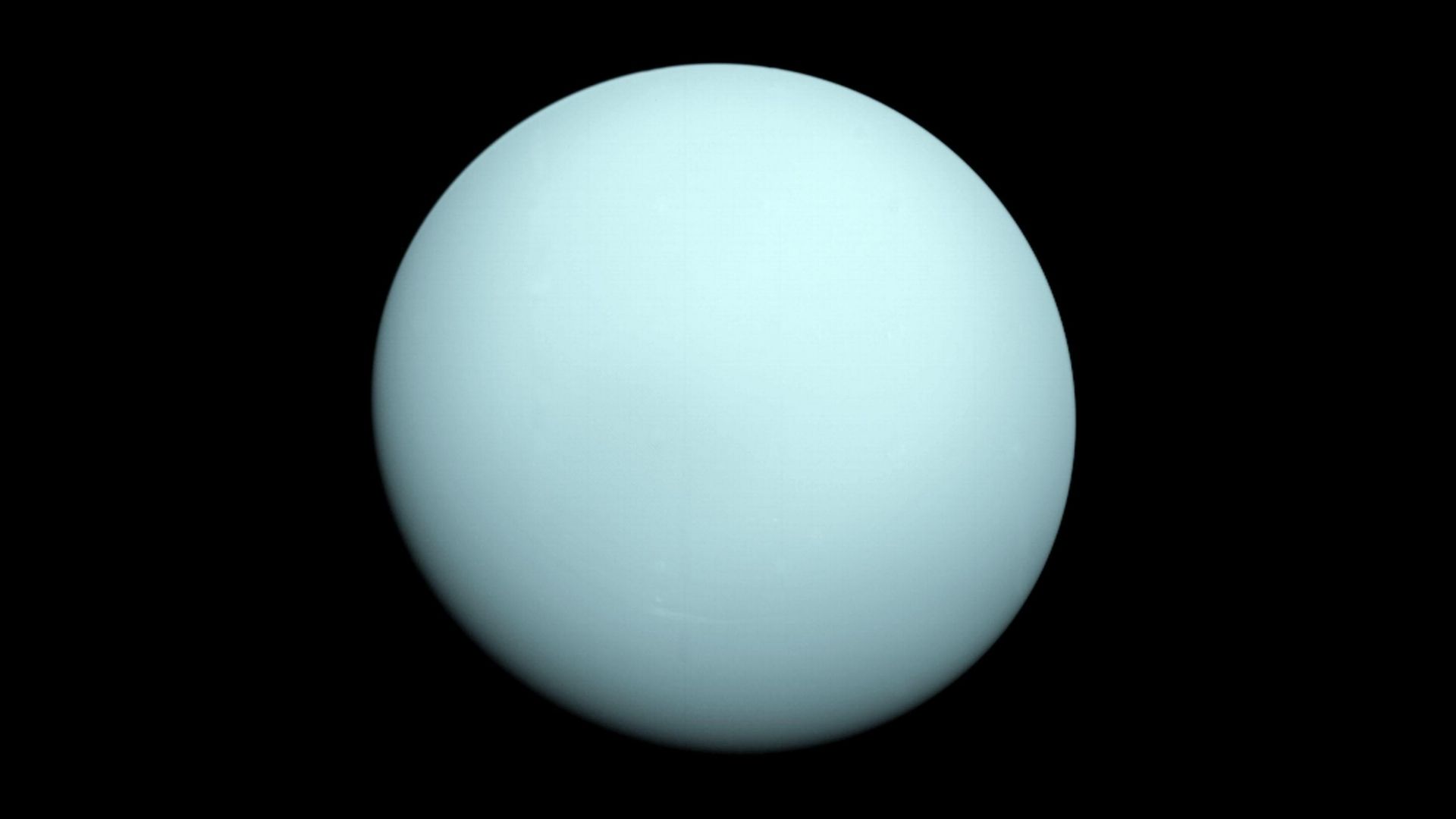

Voyager 2 alone then visited Uranus and Neptune. The spacecraft’s first-ever images of Uranus revealed dark rings, the planet’s tilted magnetic field and its geologically active moon Miranda. Neptune, meanwhile, was also discovered to have rings and many more moons than scientists initially thought. We also got to see Triton, a geologically active moon that is orbiting “backward” and, like Pluto, is now believed to be a captured dwarf planet from the Kuiper Belt.

Voyager as a catalyst

In addition to making groundbreaking discoveries, the Voyager mission helped scientists determine what merited deeper exploration. The mission revealed Jupiter to be an incredibly complex planet, thus spurring NASA to launch the Galileo mission in 1989 and the Juno mission in 2011. The Voyager probes’ work also helped to inspire the iconic Cassini mission to Saturn.

“Voyager 1’s close flyby of Titan was the catalyst for the wonderful Cassini mission to Saturn and its Huygens probe,” Lunine said. The Huygens probe landed on the surface of Titan in 2005 and sent back an incredible video.

Voyager 2 has also been a catalyst for investigations into the role of the ice giant planets — not only in the solar system but also in distant star systems, since most of the exoplanets found so far are roughly the size of Neptune and Uranus.

Voyager and NASA today

NASA has spent decades following up on the Voyager missions, and those efforts continue today. The space agency’s Dragonfly mission will reach Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, in 2034, while Europa Clipper will study Jupiter’s ocean moon, first imaged by Voyager, starting in 2030. In April, the National Academies Planetary Science Decadal Survey recommended that NASA send a $4.2 billion Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission to unveil the mysterious ice giant planet and its moons in the 2040s.

It’s the latest mission that’s a direct consequence of Voyager 2’s brief visit to the Uranus system in January 1986. “Voyager 2’s flyby of Uranus was a bull’s-eye — it went directly through the plane of the moons’ orbits because of the orientation of Uranus’ axis to the sun,” Lunine said. That made it unlike flybys at other planets, where the probes were able to visit one moon after another. “Voyager 2 got very brief images from these moons, so they’re largely unexplored,” Lunine said.

Ariel and Miranda, in particular, are thought to be ocean worlds and so would be specifically targeted by the Uranus Orbiter and Probe. “It’s been 45 years since the launch of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, and here we are now finally talking about a Uranus Orbiter and Probe mission,” Lunine said. “It seems like a long time because these missions take so long to conceive of, fund, build, launch and execute, but it all comes from the intriguing peeks that we got from Voyager 2.”

How long will Voyager last?

Both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 still communicate with NASA’s Deep Space Network (which itself was created to communicate with Voyager 2 at Uranus and Neptune), receiving routine commands and occasionally transmitting data to Earth. “We are still getting data from Voyager,” Stamatios Krimigis, principal investigator for the Voyager 1 and 2 probes and the Voyager Interstellar Mission, said during a news conference held at COSPAR 22 in July. “We’re looking forward to getting data for probably another five or six years.”

Around the mid- to late 2020s, the probes’ scientific instruments will be entirely switched off, and eventually, the spacecraft will go cold and silent — but their journeys into interstellar space will continue indefinitely. “My motto is, I want to be here after Voyager passes on,” said Krimigis, who is in his 80s. “But I’m not sure that’s going to happen.”

In around 300 years, Voyager 1 and 2 will enter the Oort cloud, the sphere of comets surrounding the solar system. About 30,000 years later, they’ll exit the neighborhood and silently orbit the center of the Milky Way for millions of years.

Their scientific work may be almost over, but the Voyager spacecraft have only just begun their journeys into the cosmos.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.