Of the eight new and renovated galleries debuting with the reopening of the National Air and Space Museum (opens in new tab), none may be more anticipated than “Destination Moon.”

A replacement for the highly popular “Apollo to the Moon,” an exhibition that launched with the museum just four years after the last astronauts stepped off the lunar surface, “Destination Moon” goes above and beyond what its predecessor displayed by building upon the Smithsonian’s unrivaled collection of Mercury, Gemini and Apollo artifacts.

The new gallery shows how a “combination of motivations, resources and technologies made it possible for humans to walk on the moon — and how and why we are going back today,” as the museum describes on its website.

Thousands of people with free, timed-entry passes (opens in new tab) are set to experience “Destination Moon” for the first time, as the doors to the National Air and Space Museum opened on Friday (Oct. 14). For those unable to be in Washington, D.C., collectSPACE.com has worked with the museum’s staff to assemble this multimedia walkthrough (opens in new tab), highlighting many of new gallery’s artifacts and installations.

Related: Lunar legacy: 45 Apollo moon mission photos

Destination ‘Destination Moon’

The “Destination Moon” exhibition is on the second floor of the Air and Space Museum, located between the “Keith C. Griffin Exploring the Planets” and “One World Connected” galleries. For those who remember “Apollo to the Moon,” (opens in new tab) its successor is now on the opposite, west side of the building.

Upon entering the gallery, just below the title plaque, visitors find a description of what the exhibition seeks to address.

“For centuries, humans dreamed of flying to the moon. In 1969, American astronauts finally set foot on its surface. What are the origins of this achievement? How was it done in less than a decade? What has happened since the moon race ended? Discover the inspiring story of how we are exploring our nearest neighbor in space,” the plaque reads.

Turning to the left, the gallery’s exhibits begins with “Fly Me to the Moon,” a series of wall-mounted displays tracing the history of flights to the moon beginning well before anyone or anything left Earth. “Fictional lunar voyages go back 2,000 years. But not until the mid-20th century could we actually send spacecraft there.”

Related: Apollo 11: First men on the moon

Above reproductions of Galileo Galilei’s sketches of the moon and the cover art for Jules Verne’s “From the Earth to the Moon” is the 40-foot-long (12 meters) original oil painting “Lunar Landscape” by space artist Chesley Bonestell.

“On March 28, 1957, six months before the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the Boston Museum of Science unveiled this huge mural in the lobby of its Charles Hayden Planetarium. Bonestell portrayed the moon as everyone expected it to be: with sharp peaks, jagged canyons, and steep crater walls. In 1970, the museum took the mural down after pictures from the moon showed that the constant rain of meteorites and space dust rounded off lunar hills and mountains. The Smithsonian acquired the mural in 1976 and restored it for this exhibition.”

Racing to the moon

Still facing the same wall, the displays advance from imaginary voyages to the real races to reach the moon. “In September 1959, [the Soviet Union’s] Luna 2 became the first spacecraft to succeed in crashing into the moon. A month later, a television camera on Luna 3 returned the first images of the moon’s far side.”

Suspended above visitors’ heads here is a reconstruction of a Pioneer probe. Made from test parts, the artifact represents the United States’ first failed attempt at launching to the moon.

Next to Pioneer is a one-third scale model of Vostok, the Soviet spacecraft that carried the world’s first man (Yuri Gagarin) and woman (Valentina Tereshkova) into space. Also on exhibit here (at ground level) is a bronze bust of Gagarin and the capsule that NASA used to send chimpanzees prior to humans into space.

Turning to face the windows at the far end of the hall, visitors come face to face with both the silvery pressure suit worn by Alan Shepard, America’s first astronaut to fly into space, and his Mercury spacecraft, “Freedom 7.” (opens in new tab) The two artifacts are reunited in “Destination Moon,” having previously been displayed in separate museums. The suit was restored for this exhibition as part of the Smithsonian’s first crowd-funding campaign.

Also on display: the Capsule Flight Operations Manual that Shepard used to prepare for his Mercury-Redstone 3 suborbital flight.

Taking a few steps back and turning to the right, visitors enter “A Huge Challenge,” the next area in “Destination Moon” gallery. “How could America land humans on the moon in less than 10 years? President Kennedy’s decision presented enormous challenges.”

On the right is a wall of displays examining the impacts that the space program had on the nation, including the contributions of contractors from across the country and around the world. Here you can see the jacket belonging to McDonnell Aircraft’s chief engineer for Project Mercury and Project Gemini, an Apollo survival knife (opens in new tab) made by W.R. Case and Sons Cutlery and the Omega Speedmaster chronograph worn by Gordon Cooper on Gemini V, among other example artifacts.

Along the same wall is a look at how women and civil rights played into and were affected by the expansion of NASA facilities, especially in the Deep South.

Opposite the wall is a display case with the Gemini VII spacecraft that Frank Borman and Jim Lovell lived in while orbiting Earth for two weeks, The Gemini missions honed the skills needed to safely send astronauts safely to the moon.

In the same case are artifacts from the first American spacewalk, including astronaut Edward White’s helmet, his hand-held maneuvering unit and life support umbilical, as well as the harmonica and jingle bells flown on Gemini VI-A, which demonstrated rendezvous with the Gemini VII capsule.

Related: The Gemini program: Two-person prep for moon missions

Below and above

Returning to the opposite wall, past a display of 1:48 scale models of NASA’s Mercury, Gemini and Apollo launch vehicles, is the largest and heaviest artifact in “Destination Moon.” To see it, visitors only need to look up.

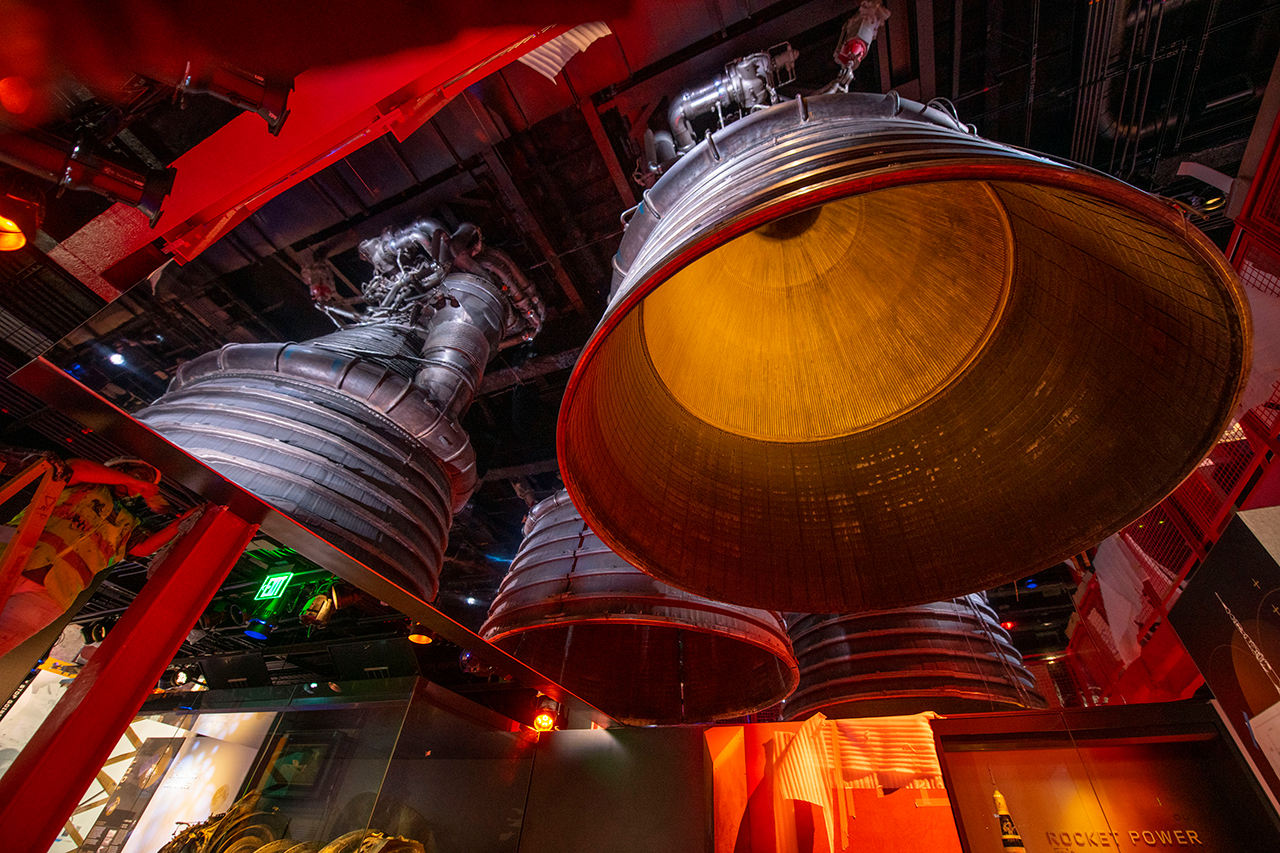

But wait, do you see five Saturn V F-1 rocket engines? Mirrors create the illusion of standing under the Saturn V inside the flame trench, but in reality there is only one complete F-1 — an early test engine that was fired four times — and a one-quarter section from an example of a center-mounted engine.

In the former “Apollo to the Moon,” the F-1 engine and section piece were also mounted with mirrors but in the horizontal. Raising the display into the vertical was the largest challenge the museum faced during the renovations.

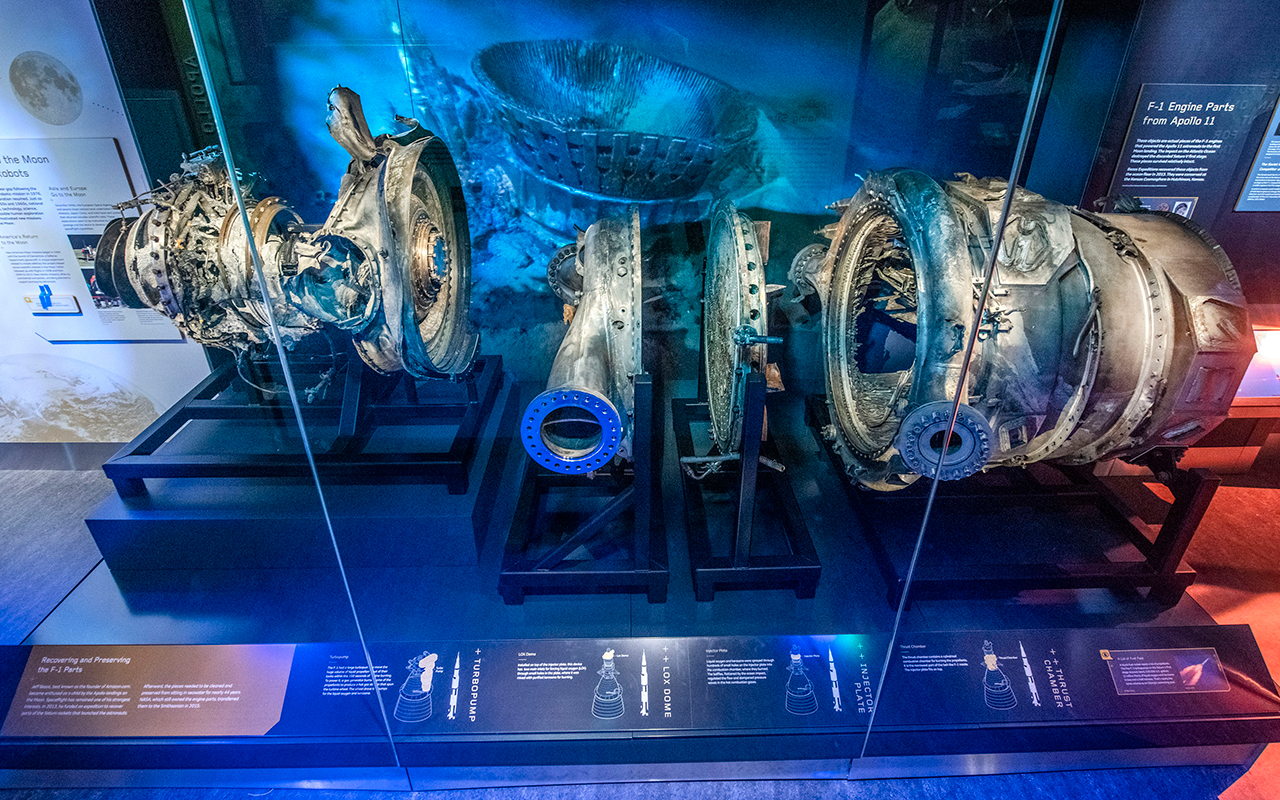

Just beyond the suspended F-1 display is a glass case with the parts from another F-1, one of the five that launched the Apollo 11 mission. The turbopump, LOX (liquid oxygen) dome, injector plate and thrust chamber were recovered off the ocean floor in 2013.

Turning around to look back toward the Gemini display case, visitors ascend the stairway to the gallery’s mezzanine (an elevator is also available). The red hue of the staircase is intended to evoke the Apollo-era mobile launcher gantry that stood beside and supported the Saturn V.

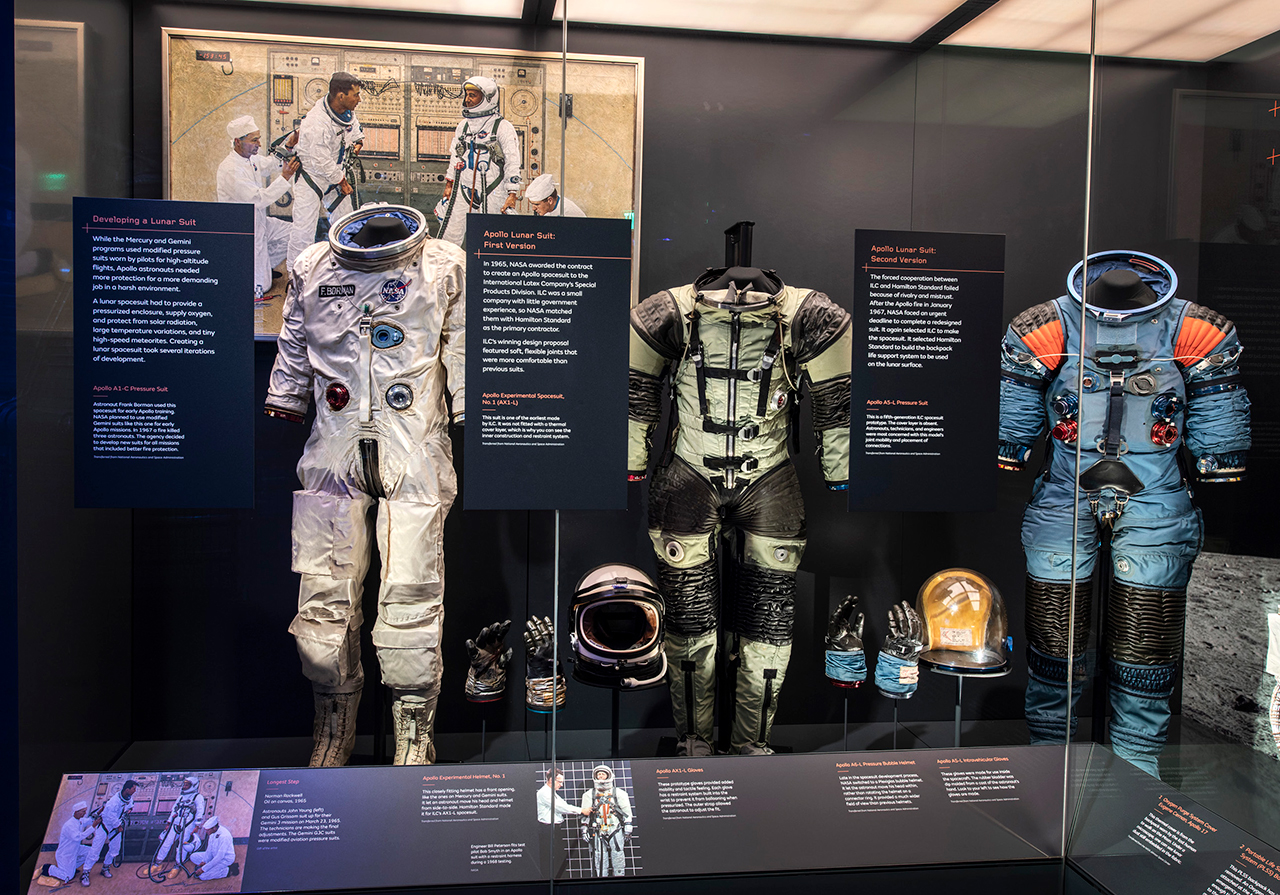

Ascending the stairs, visitors encounter “Outfitting and Guiding the Astronauts,” the next set of displays. “To send astronauts to the moon, NASA had to develop new ways to train, equip and guide them. The Apollo crews needed lunar spacesuits, along with supplies and equipment for one to two weeks in space.”

Here are examples of how the spacesuits astronauts would come to wear on the moon were developed and evolved, from the Apollo I-C pressure suit that Frank Borman used for his early Apollo training to prototypes that led up to the spacesuit used on the lunar surface.

A portable life support system (or PLSS) backup is displayed without its cover, revealing its inner workings, next to a sewing machine that seamstresses used to sew the fabric portions of the Apollo spacesuit.

Continuing along the mezzanine, beyond exhibits dedicated to space food, astronaut personal hygiene equipment and survival tools, visitors re-encounter the F-1 engine now at eye level. The 18-foot-tall (5.6-m), 18,000-pound (8,200 kilograms) engine is complimented by plaques helping describe what is now visible and up close.

Past the F-1, visitors come across “Simulation and Mission Control,” featuring the instructor control console and “star ball” from the Apollo command module simulator that was in use at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, as well as displays describing the Mercury and Apollo mission controls.

Before leaving the mezzanine, visitors encounter one more exhibit devoted to what may be the most famous role for mission control. “Houston, We’ve Had a Problem” presents flight director Gene Kranz’ Apollo 13 vest and how the astronauts were able to fit “a square peg” (a command module lithium hydroxide canister, or carbon dioxide scrubber) in “a round hole” (the receptacle for lunar module lithium hydroxide filter).

Related: Apollo 13: Facts about NASA’s near-disastrous moon mission

Humans reach the moon

Descending the stairway opposite the one they ascended, visitors now cross the room, past that first staircase, where the Apollo program begins in “Destination Moon.”

Here, the Apollo 4 command module inner and heat shield hatches are on exhibit next to the Apollo 11 command module hatch showing the changes that were made after a fire on the launch pad claimed the lives of the Apollo 1 crew. Additional wall-mounted displays detail the missions that came before a lunar landing, from Apollo 7 through Apollo 10.

Overhead, a Ranger probe (at right) assembled from spare parts and an engineering model configured like the Surveyor 3 lander represent the robotic precursor missions that helped made a crewed moon landing possible.

Returning to the base of the stairs where visitors descended from the mezzanine, they come to Neil Armstrong’s Apollo 11 spacesuit.

“Neil Armstrong wore this spacesuit when he made his historic ‘one small step’ onto the surface of the Moon on July 20, 1969. Before and after his two-and-a-half-hour lunar walk, he wore it inside the lunar module, but without the special gold visor helmet and with different gloves,” the display reads.

Behind the spacesuit located in its own display case is the centerpiece of “Destination Moon,” the Apollo 11 command module “Columbia.” Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins flew to the moon and back aboard this spacecraft.

Continue the tour with “Columbia” and much more (opens in new tab) by clicking through now to collectSPACE.

Follow collectSPACE.com (opens in new tab) on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE (opens in new tab). Copyright 2022 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.