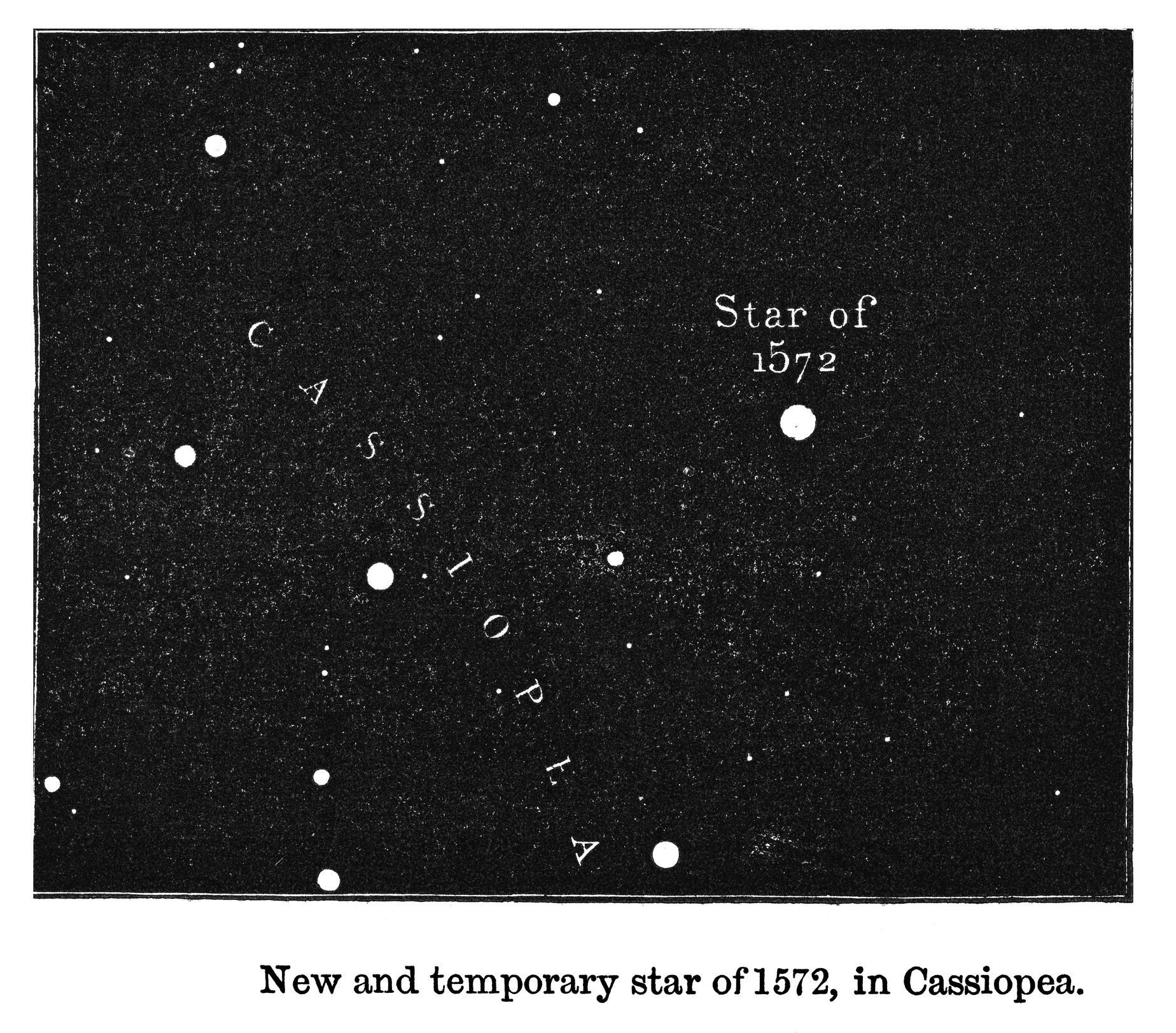

One of the most spectacular celestial sights ever seen suddenly appeared in the northern night sky 450 years ago this month: a “new” star in the constellation Cassiopeia (the Queen). It was the most brilliant nova recorded in some 500 years and, to this day, remains one of only five known supernovas observed in our Milky Way galaxy.

To get an idea of just how dazzling this object was, step outside an evening this week at around 8 p.m. local time and look high up toward the north-northeast sky at the familiar zigzag row of five bright stars that make up the “W” of Cassiopeia. Next, look toward the south-southeast at the brilliant planet Jupiter, shining like a silvery beacon, and try to imagine what it would look like if you could somehow ramp up its brightness eightfold. Then, turn back to look at Cassiopeia. Try to visualize such a dazzling object in that region of the sky, and you will get an idea of what this strange new star must have looked like to those living in the late 16th century.

On Nov. 6, 1572, German astronomer Wolfgang Schüler of Wittenberg was the first to notice the appearance of this new star adjacent to the dimmest star at the center of Cassiopeia’s W.” Over the next three days, the strange interloper was sighted by many other skywatchers.

Related: Night sky, November 2022: What you can see tonight [maps]

Seeing is believing

When this stellar object made its first appearance, it likely was no brighter than an ordinary star. But when it was spotted by Danish astronomer and nobleman Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) on Nov. 11, 1572, the star rivaled Jupiter in brightness and, in the nights to follow, became equal to Venus at its most brilliant. Tycho himself was probably bowled over by this dazzling object and actually stopped people in the street, pointed skyward and asked them to verify what he was seeing.

From his own written account of his discovery, he noted the following, according to “Burnham’s Celestial Handbook, Volume 1 (opens in new tab):”

“On the eleventh day of November in the evening after sunset … I was contemplating the stars in a clear sky. […] I noticed that a new and unusual star, surpassing the others in brilliancy, was shining almost directly above my head; and since I had, from boyhood, known all the stars of the heavens perfectly, it was quite evident to me that there had never been any star in that place in the sky (opens in new tab), even the smallest, to say nothing of a star so conspicuous and bright as this. I was so astonished at this sight that I was not ashamed to doubt the trustworthiness of my own eyes. But when I observed that others, on having the place pointed out to them, could see that there was really a star there, I had no further doubts. A miracle indeed, one that has never been previously seen before our time, in any age since the beginning of the world.”

For the next two weeks, the nova far outshone every star in the sky and could even be readily seen through the brilliance of the blue daytime sky, suggesting that it might have briefly rivaled Venus’ brightness. As November came to a close, the nova began to fade gradually, changing from a resplendent silver to yellow, then orange, then a reddish luster, before finally fading completely from view in March 1574, after having been visible to the naked eye for some 16 months.

What did it mean?

Naturally, many people immediately thought of the Star of Bethlehem, seeing it as a sign placed in the heavens presaging the second coming of Christ.

But Tycho rejected this interpretation and pointed out that the star described in the Book of Matthew had been visible only to the Magi and, therefore, could not have been a heavenly body. Others speculated about the calamities it might bring. And it also seemed to throw a monkey wrench into the teachings of Aristotle, who, in his vast authority, had asserted that the world of stars was eternal and invariable.

Where did it come from?

So, what could this strange star have meant? For the rest of his life, Tycho puzzled over the mystery. He went on to write an extensive work, “De nova et nullius aevi memoria prius visa stella,” meaning “Concerning the star, new and never before seen in the life or memory of anyone.” The new star was neither a planet nor a comet, for it remained in the same place against the background stars through its entire run of visibility. These measurements clearly established that this strange heavenly body lay beyond the moon, in the realm of the fixed stars. Had it been nearer, Tycho would have detected a displacement as it moved across the sky. Thus, he concluded that Aristotle was wrong; the stars were not invariable. Tycho advanced a theory that the star had possibly formed as a condensation from dark matter of the Milky Way, even pointing out a dark area from which such a condensation might have occurred.

Greek astronomer, geographer and mathematician Hipparchus (190 B.C.-120 B.C.) had also recorded new stars, though none was as stupendously bright as the one in 1572. “So perhaps,” Tycho reasoned, “the matter of the Milky Way occasionally coagulated into a star.” But any such star would also have to quickly fade, “for anything that arises after the completion of the Creation can only be transitory.”

Tycho’s account of the changes in brightness and his position measurements form a valuable record for modern researchers and scientists; in his honor, this amazing object is often dubbed Tycho’s star.

A colossal blast

In Latin, such a star was referred to as a “stella nova,” or “new star.” Today, we still call this kind of star a nova, though we know it’s far from new. In fact, modern observations reveal that we’re seeing the star exploding. Some of these explosions are not very great, but others are devastating, changing the entire character of the star. Indeed, these stars are far from being new; they are near the ends of their lives and really ought to be called dying stars.

The internal temperatures of such stars can reach as high as 5 billion degrees Fahrenheit (2.8 billion degrees Celsius), where nuclear fusion makes elements as heavy as iron and ultimately results in an enormous explosion — a supernova. Tycho’s supernova of 1572 was categorized as a Type Ia (“Type one A”) supernova, which occurs when a white dwarf star pulls material from, or merges with, a nearby companion star until a violent explosion is triggered. The white dwarf is obliterated, sending its debris hurtling into space.

The smoking gun

For decades, the only remnants of the 1572 explosion were very faint shreds of nebulosity visible only in large telescopes; most of the residual debris cloud is all but invisible due to insufficient illumination. But in July 1999, the Chandra X-ray Observatory was placed into Earth orbit from space shuttle Columbia. It is sensitive to X-ray sources 100 times fainter than any previous X-ray telescope, and when it was trained toward Tycho’s supernova remnant, the first light image was finally obtained. A compact object at the center of the remnant revealed an intriguing pattern of bright clumps and thickets of knots and fainter areas — which could be a neutron star or even a black hole.

The distance to Tycho’s star is estimated to be somewhere between 8,000 and 9,800 light-years, which implies that, at its maximum, this bursting star had an actual luminosity of about 300 million times that of the sun! Such a star, in the course of just a few days, radiates into space an amount of energy equal to the entire output of the sun for several million years.

Repeat performance anytime soon?

Will we ever have a chance to witness another stellar explosion similar to Tycho’s supernova in our lifetimes? Maybe. In the past 1,000 years, only five supernovas (opens in new tab) have been witnessed and recorded in our galaxy: A very bright new star that appeared in the southern constellation Lupus (the Wolf) in A.D. 1006; a brilliant supernova that erupted in the constellation Taurus (the Bull) in A.D. 1054; one seen by Chinese astronomers (opens in new tab) in 1181; Tycho’s star in 1572; and a supernova in 1604 that was extensively studied by German astronomer Johannes Kepler.

This suggests we should expect a supernova to appear at roughly 250-year intervals, on average, and based on that time frame, we are long overdue for another. And yet, twice we have had two supernovas occur within less than 50 years of each other, followed by a wait of over 500 years until the next pair, again separated by less than 50 years. Going by that odd time frame, we might not expect to see another until well into the 22nd century.

Still, nobody can say for certain when the next supernova will illuminate our skies. It might just be tonight, which is as good a reason as any to keep looking up!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium (opens in new tab). He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine (opens in new tab), the Farmers’ Almanac (opens in new tab) and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).