NASA’s latest flagship telescope is still in its first year of science, but the agency isn’t only hard at work building its successor — it’s starting to plan that next mission’s successor as well.

In November 2021, a decadal document produced by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences directed NASA’s astrophysics division to concentrate its efforts on the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, currently targeting launch in the mid-2020s. But the report also nudged NASA to get a start on the subsequent flagship astrophysics mission, which it recommended be a space telescope observing in infrared, optical and ultraviolet light that could search for habitable exoplanets and signs of life on them.

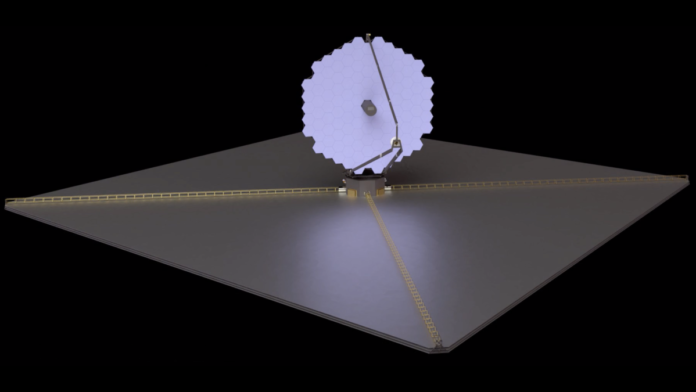

Now, NASA has offered its first glimpse of what that mission will look like. For now, it will be known as the Habitable Worlds Observatory, Mark Clampin, the director of NASA’s astrophysics division, said during a presentation on Monday (Jan. 9) at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society held this week in Seattle and online.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope’s best images of all time (gallery)

First, despite the name and goal, NASA is considering the project an astrophysics mission, Clampin said. To meet its mission of searching for life, the Habitable Worlds Observatory will need to be a super-stable telescope equipped with a powerful coronograph, an instrument that allows scientists to study faint objects like rocky planets near bright objects like stars. But that’s a powerful combination for astrophysicists as well.

“Even though you may at first blush look at it and say, ‘Well, this is an exoplanet mission,’ it’s not; it’s an observatory,” Clampin said.

The National Academies of Sciences document, nicknamed the decadal survey, also noted that NASA should use small missions to develop X-ray and far-infrared observing technologies that can be used on two large space telescope missions that should later join the Habitable Worlds Observatory to bring more power to a wider range of wavelengths.

It’s clear that NASA doesn’t want to see the construction of the Habitable Worlds Observatory turn out like that of the James Webb Space Telescope (Webb or JWST) did, blowing through both timelines and budgets with effects that rippled through agency projects. Clampin noted that the agency will be approaching the Habitable Worlds Observatory as if the spacecraft faced a strict launch window dictated by solar system dynamics, the way planetary science missions often do.

He said the approach should also keep the project’s budget in line, and keep the agency moving toward the large X-ray and far-infrared missions as well. “The faster you get it done, the sooner you can also think about the next two great observatories,” he said of the Habitable Worlds Observatory.

Fortunately, the new telescope will be starting on much firmer technological territory than JWST did: It will build directly on JWST’s pioneering segmented mirror, as well as the powerful chronograph that will fly on the Roman Space Telescope, Clampin emphasized.

The new mission will also have a backup plan built in, he said. The Habitable Worlds Observatory, like JWST, will be perched 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from Earth opposite the sun, at a spot known as Earth-sun Lagrange point 2 or L2. But unlike its neighbor, the future observatory will someday benefit from robotic upgrades.

“We’re also going to plan this mission from day one to be serviceable,” Clampin said. That decision will build on the success of the venerable Hubble Space Telescope, which was first rescued and then given powerful new instruments during five visits from astronauts, most recently in 2009. The approach will also make use of hefty commercial investments in robotic servicing, which made history in 2020 when a commercial satellite took over orbit maintenance for an aging internet satellite. (Hubble orbits just a few hundred miles above Earth, so it’s relatively easy for astronauts to get to. Crewed servicing missions all the way out to L2 are not feasible at this point.)

“In 10, 15 years, there are going to be a lot of companies that can do very straightforward robotic servicing at L2,” Clampin said. “It gives us flexibility, because it means we don’t necessarily have to hit all of the science goals the first time.”

NASA will turn to the commercial sector for a second key contribution as well, the launch vehicle. Taking that route should reduce the size and weight constraints the telescope will have to meet to get off the ground, Clampin said.

JWST’s tense two-week unfolding sequence, with more than 300 potential mission-ending failure points to navigate, was implemented to fit the telescope’s massive mirror and sunshield into the 15-foot-wide (4.5 m) fairing of its Ariane 5 rocket. But future rockets are being designed with much more cargo space. For example, Blue Origin‘s New Glenn rocket is designed to carry a 23-foot-wide (7 m) fairing and SpaceX‘s Starship will boast a 30-foot-wide (9 m) fairing, according to the companies.

“There are a number of commercial companies making very big fairings and launches now; we would be insane not to use them,” Clampin said. “Big fairings on big rockets give you flexibility.”

Email Meghan Bartels at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.