They say you should never judge a book by its cover, but the image fronting a new tome of astronaut photography speaks volumes for what is found inside.

The product of years of image processing work by British space and photography enthusiast Andy Saunders, “Apollo Remastered: The Ultimate Photographic Record (opens in new tab)” presents more than 400 images that visually document every mission of NASA’s first moon landing program and some of the U.S. human spaceflights that preceded them into Earth orbit. First published in the U.K. last month, “Apollo Remastered” landed on U.S. book store shelves (opens in new tab) on Tuesday (Oct. 25) from Black Dog & Leventhal.

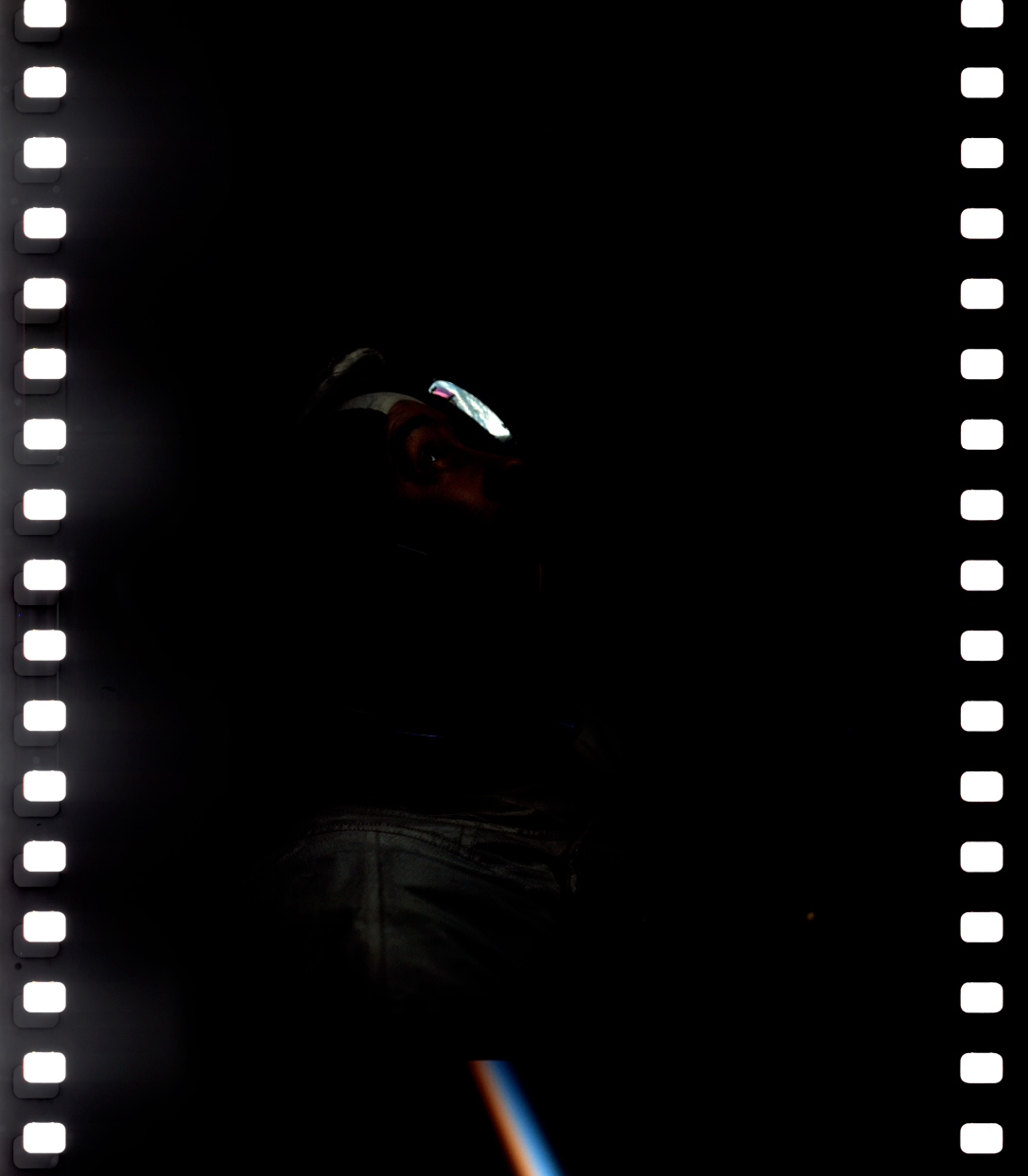

What separates Saunders’ book from past Apollo photo collections is illustrated by the photo of Apollo 9 commander Jim McDivitt on the cover. Working with a high-resolution digital file produced from the original flight film, Saunders recovered McDivitt’s image — which was taken while he performed the world’s first docking between two crewed spacecraft — from an underexposed scan. It is the only photograph to show an Apollo astronaut in their full spacesuit and bubble helmet while in flight, according to Saunders.

Related: Jim McDivitt, astronaut who led Gemini 4 and Apollo 9 missions, dies at 93

The cover now also serves as a tribute to McDivitt, who died on Oct. 13 (opens in new tab) at 93.

“I always wanted the cover to be an image that’s rarely seen and something that isn’t obvious, but also something that highlights the human side of the moon landings,” said Saunders in an interview with collectSPACE.com. “[McDivitt’s] also one of the lesser-known astronauts to the public and I want the book to remind people that Neil Armstrong wasn’t the only guy in the program and there was more than just Apollo 11. It was a pretty easy choice for the cover too from a photographic standpoint as it’s such a cinematic, atmospheric shot now it’s been cleaned up, and the lighting is sublime.”

“I was so sad to hear of Jim’s passing and it’s still quite raw — of course I have a particular affinity to him as he’s the (perhaps unlikely) poster boy of the book,” said Saunders. “I was in touch with Jim a little during research for the book and his family were thrilled about the whole thing. We managed to rush an advance copy to him only a few weeks ago and it was wonderful to learn how much he loved it, that it brought back lots of memories and how handsome he thought he looked on the cover! That meant more to me than any number of book sales.”

collectSPACE spoke with Saunders about the making of “Apollo Remastered” and his thoughts on what can be learned from the work he undertook to bring the book to print. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

collectSPACE (cS): What inspired you to work on the Apollo-era photos?

Andy Saunders: I’ve had a bit of an obsession with the moon and the Apollo missions since childhood. I always craved more and more information about the people who made the journey, the rockets, the spacecraft and I wanted to see more, to imagine what it would be like to make the journey myself. In fact, for as long as I can remember, I’ve dreamt that I could somehow travel back in time and position myself right in the action — to observe, first-hand, these historic moments unfolding before my eyes. Impossible of course, but working on the footage to make it clearer is one way I can experience something more visceral and connect more to the events. And sometimes we can even learn something new from the imagery, even 50 years later, which is a great bonus.

As a lifelong amateur, turned semi-professional photographer, I was aware of the developments in digital image processing that could help photographs look their absolute best. I was frustrated with the quality of what we typically see and it didn’t make any sense because they used the best cameras, lenses, film, etc. But because everything, for so long, has been based on duplicate film (and copies of copies of the dupes) and lower quality scans of them, the images we see have really been getting worse over time. There also tends to have been little digital processing applied to present the digital scans of analog film correctly.

Read more: South Pole’s never-ending night and daily auroras are a dream for astrophotographers

This process has only accelerated with the availability of images online (jpeg copy after jpeg copy) and these poorly presented images, that are getting progressively worse are being seen by a progressively bigger audience. That concept drove me nuts. It’s nobody’s fault, it’s just how things have developed over time — but things should get better, not worse. I can’t think of any film in existence that is more deserving of the highest level of care and attention. But we now have the holy grail — the original flight film (rather than duplicate film), via incredible high resolution, high bit depth scans and given the techniques I’d also been honing on stacking the 16mm movie footage, this led me to the decision to put my life on hold and take this huge project on.

cS: What is your basic process for producing a remastered photo?

Saunders: The key is starting with the best source footage. [Archivist] Stephen Slater provided me with the highest quality scans of the 16mm DAC [Data Acquisition Camera] footage and NASA/Arizona State University’s scans (opens in new tab) of the original flight film were used for the stills. Some of the images only require a light touch and can be completed in a few hours. More complicated stills, particularly those that are significantly under or overexposed, take closer to a day, or even longer to perfect.

Because it’s analog film, the scans do need lots of digital manipulation to look their best and balance the whole frame and to rid some areas of unwanted artifacts from the scanning process, too. The images are huge and I go into every tiny part of the frame — there is often microscopic debris on the film, picked up at some point in the last half century during handling, processing or the scanning process; and these need to be individually removed. Getting the color right for the color film is also a critical element.

Producing photo-like images from the 16mm DAC “movie” film requires an entirely different, additional process at the start of the workflow. Anything from a few frames, to hundreds of frames of a scene are aligned and stacked on top of each other. It’s a process often utilized in astrophotography to bring out details in distant planets.

I first considered its application to this footage many years ago. I figured if you could put the planet Mars through this, why not Neil Armstrong!? I never cease to be amazed how powerful this process is. It effectively maintains the signal in each frame but averages out the noise. The improvement in the signal to noise ratio brings out astonishing detail — detail that simply doesn’t exist in a single frame, and makes the images more photo-like and also more able to then receive the type of digital enhancement that I apply to the Hasselblad stills, too.

Read more: Astronaut’s gold Omega moonwatch sells for record $1.9M at auction

This DAC was great at capturing the cramped inside of the spacecraft, better than the Hasselblad still cameras due to wider angle lenses. The innate desire to see inside the spacecraft; to appreciate what our first moon-bound vehicles of the 1960s looked like, and to observe life on board these most historic journeys drove me to make the effort to enhance this footage in addition to the stills.

I’ve basically assessed every frame of film, from every camera, that was captured during every flight of the whole program. The difficulty with much of the “movie” footage, however, is that it was shot handheld, by an astronaut floating in zero-G, with the subject matter (other astronauts) and also other items floating around in the shot. It’s impossible to align and stack this footage. So I had to develop a new process that allowed me to handle all of this movement and still align everything and benefit from the signal/noise improvements.

This new process has also allowed for panoramic shots to be produced as the camera pans around — these images could take days to complete, but they now give us a unique look inside these 1960s spacecraft and their spacefaring explorers on what are arguably the greatest ever human expeditions.

cS: There is a “look” to vintage Apollo photographs that many have come to associate with the iconography of the program. What do you think remastering adds? And do you think anything is lost in the process?

Saunders: Great question. It was very important to me from the start that the restorations were undertaken sympathetically and accurately, respecting the historical importance of the content. I want this to be an authentic record and I want the reader to feel like this is as close as they can get to making the journey themselves, to see what the astronauts saw, as they saw it.

I don’t use any AI-based software or any automated features in remastering the footage. I don’t want a computer “inventing” and inserting pixels into this kind of historical content. It’s essential for me to know exactly what was there in the first place, what I’ve adjusted and what is there at the end.

A huge amount of research went into understanding the visual in space. I researched post mission reports, all of the photography training materials, learned about the cameras — how they worked and how they were used, as well as going through the mission transcripts and tapes to glean information from what the astronauts were saying as they witnessed what they photographed.

Digital processing is simply a more powerful and efficient way of improving photographs with similar techniques that were also used in the dark room in the analog world. We’re not adding or taking anything away, simply improving what’s there. It’s actually something you simply must do with digital scans of analog film, period. It’s a prerequisite to present them correctly because the analog film was never designed to be digitally scanned of course, the slides were designed to have light penetrate them onto light-sensitive photo paper or projected. Much of what we see looks “vintage” but actually it’s just a poor representation of what is an incredibly high quality piece of analog film captured by some of the best cameras and lenses ever developed — there’s no reason they should be viewed this way.

The astronauts became extremely adept at taking photographs (despite no viewfinder or automatic settings) but occasionally got it a little wrong. I actually love those shots because those imperfections remind us that a human took the photograph in this extraordinary environment! A great example is near the end of the book — commander Gene Cernan on Apollo 17 in the lunar module after the last EVA [moonwalk], looking filthy and exhausted. There’s some major camera shake going on but it just makes the whole shot. It’s so raw, so human and so extraordinary when you think about where they are.

For these reasons I also try not to crop or rotate the images if it isn’t strictly necessary. I also leave on the fiducial markers (cross hairs) that are absolutely synonymous with Apollo photography and all part of the visual storytelling.

cS: Was there a temptation to show a before and after for each photo in the book?

Saunders: That was actually a serious consideration for a while as an appendix, partly for provenance, but we quickly realized it wasn’t particularly interesting when most of the RAW files effectively look like a very, very dark square! It would also take up too much space. With the desire to make this the “definitive photographic record” of the whole program, it was more important to use that space for even more full page remastered images. There’s over 400 large-scale photographs in the book, which is very unusual, and it literally became a case of, “at what point does this already huge, heavy book become too unwieldy!?”

I’m also slightly uncomfortable when much of the media focus has been on before and after shots. The transformation is huge but it’s not like the data isn’t there. Anyone who knows about digital imagery will know just how much you can pull from a high bit-depth raw file. The trick really is making that output, that’s now visible, look half decent and worthy of presenting. It’s that bit that takes a huge amount of time. And I’m keen that the book isn’t seen as simply taking unusable images and making them great — there are those moments but the book covers the whole spectrum; all the classic iconic shots too — many of which require less work but we can now see them with a detail, clarity and accuracy we haven’t seen before.

cS: Do you have a favorite Apollo-era photo?

Saunders: It’s so difficult to choose! I like many for very different reasons. They took 35,000, so even whittling those down to 400 hundred for the book was a near impossible task.

There are images of historical significance, images that reveal something entirely new, images that instantly convey the awe inspiring nature of human space exploration and there are so many that are simply stunning — what better subject matter than fellow humans doing extraordinary things with the backdrop of 1960s spacecraft and scenes that are literally other-worldly? There are also panoramic shots that are great at showcasing the scale and grandeur of the lunar landscape.

But I think it’s the moments that capture the human side to the missions, these intimate, candid moments that I’ve managed to reveal that I like the most. The image of Armstrong on the lunar surface will be difficult to beat because of the historical significance, but the photograph on the cover has it all. It’s such an atmospheric, cinematic portrait and it’s an image that was in such a bad state before and so rarely seen.

And it’s also a historic moment as McDivitt is undertaking the first ever docking in space between two crewed spacecraft (with internal transfer). Rusty Schweikart also told me just how difficult a task this was for any pilot and how hard McDivitt was focusing in this moment. Remember they were in a spacecraft with no heat shield and therefore incapable of getting them home if they failed to dock and get to the command module.

cS: What lessons can NASA learn from “Apollo Remastered (opens in new tab)” with regards to the approach to photography during the Artemis program?

Saunders: Of course the imagery during Artemis will be very different to that of our first voyages to the moon. In today’s digital world we can capture an almost limitless number of photographs but back in the 60’s we were limited to only 200 photographs per magazine.

Another key difference is that we won’t need to wait for the astronauts to return to Earth to see the incredible images. We’ll have 4k live streaming, 360 degree field-of-view, virtual reality enabled footage.

I do hope that public affairs photography will be higher up the agenda than during Apollo. Understandably back then it was a case of “let’s focus on getting there and back safely” as well as using the precious little film for scientific purposes. The key was not to idolize the people doing the work, but the work itself. However there are certain types of images, angles, points in the missions that provide the opportunity to produce images that transcend documentation. These must be captured. We have to inspire people and get people behind human spaceflight — to do that we need to see the humans themselves. I’d actually love the opportunity to share all of these thoughts and lessons from the Apollo photography with NASA as they plan our return to the moon.

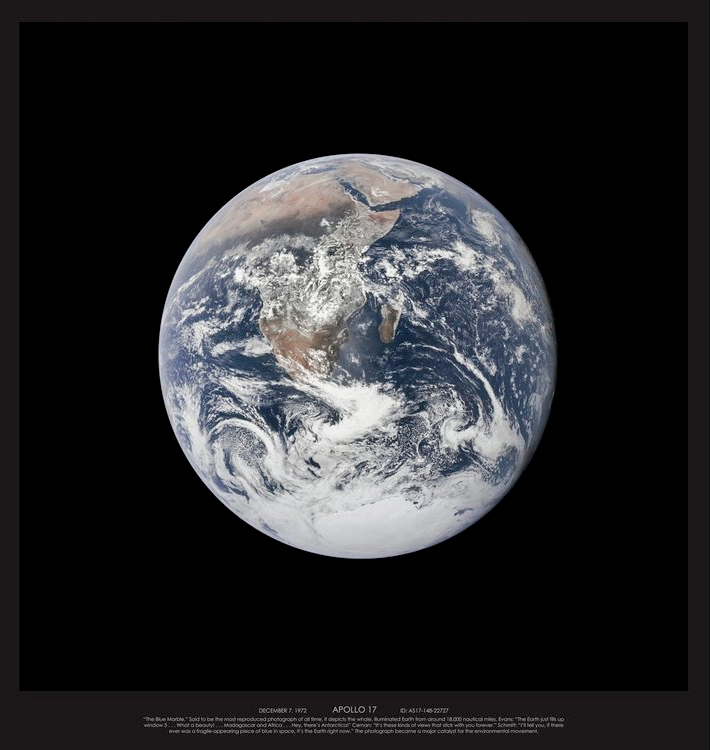

Just think of the “Blue Marble” photograph of Earth from Apollo 17. It’s said to be the most reproduced photograph ever taken. We see it everywhere, but it doesn’t always hit home when we don’t have the context. Many people may think it was taken by an uncrewed spacecraft for example, and simply note that it’s a “nice image” without thinking about it.

But what I try to do in the book is put photographs like this into context — for example, what photographs were taken just before and just after it? What were the astronauts doing or saying at the time? When we consider the fact that the photograph was taken by a human; one of us, in a spacecraft speeding away from his home planet on a journey to the moon, and this was the view from his window that he captured on film — WOW! It’s that human element that makes it even more special.

I have absolute confidence that on Artemis II (opens in new tab), another one of us, for the first time in over half a century, will take a similar photograph of our whole planet and it will be seen by almost everyone on Earth. We will all look back at ourselves and consider our place in the universe, and it will remind us of what we have. No doubt comparisons will be made to how much (or maybe how little) has changed in 50 years. It will have another enormous impact on the environmental movement, too.

We have had to wait 50 years to apply quite unusual digital processing to the old film to simply see a clear image of the first man on the moon. I do hope we remember to take a photograph of the first woman on the moon! But capture the right moments and the imagery from Artemis will become seared into our collective memories for decades to come and the absolute gems will last forever. But can Artemis, and digital photography, truly match the romance of old analog film capturing that pioneering, golden era of the 1960’s? That remains to be seen…

Follow collectSPACE.com (opens in new tab) on Facebook (opens in new tab) and on Twitter at @collectSPACE (opens in new tab). Copyright 2022 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.