It can now be revealed that NASA’s Orion spacecraft, which is just a day away from returning to Earth, carried secret messages to the moon on its Artemis 1 mission.

What’s more, the hidden notes were in plain sight (opens in new tab) the entire time.

“We do have some Easter eggs in the view of the cockpit. So when you do get that view, happy hunting folks!” said Mike Sarafin, NASA’s Artemis mission manager, on Nov. 18, the third day of the 25.5-day Artemis 1 mission. By “Easter eggs” he was using the term generally associated with software or films to describe a hidden feature.

NASA then went quiet on the topic. That is, until today (Dec. 10), when the agency revealed the locations and meanings behind the stealthy missives.

Related: 10 strange things Artemis 1 took to the moon

Spoiler warning: If you want more time to find the “eggs” yourself, pause reading here until you are ready to check what you found.

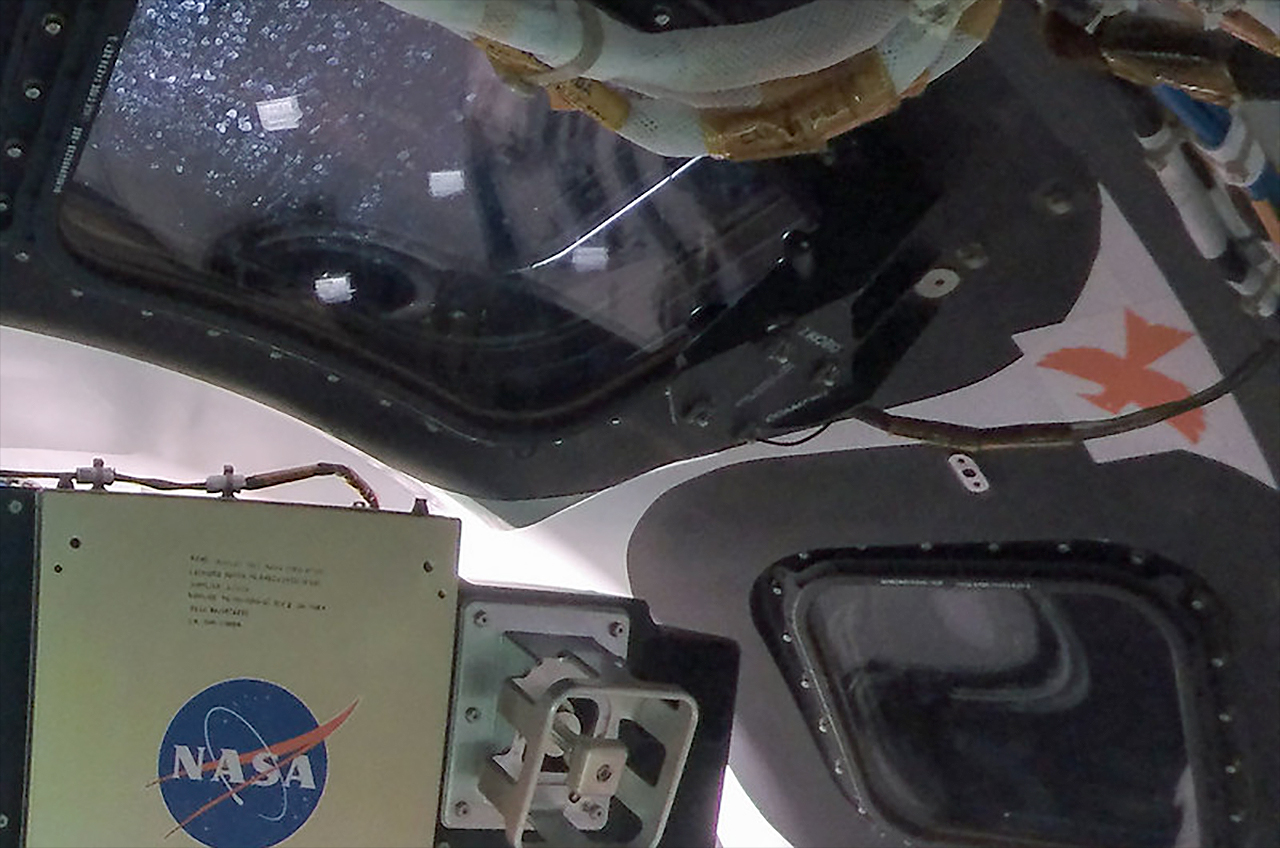

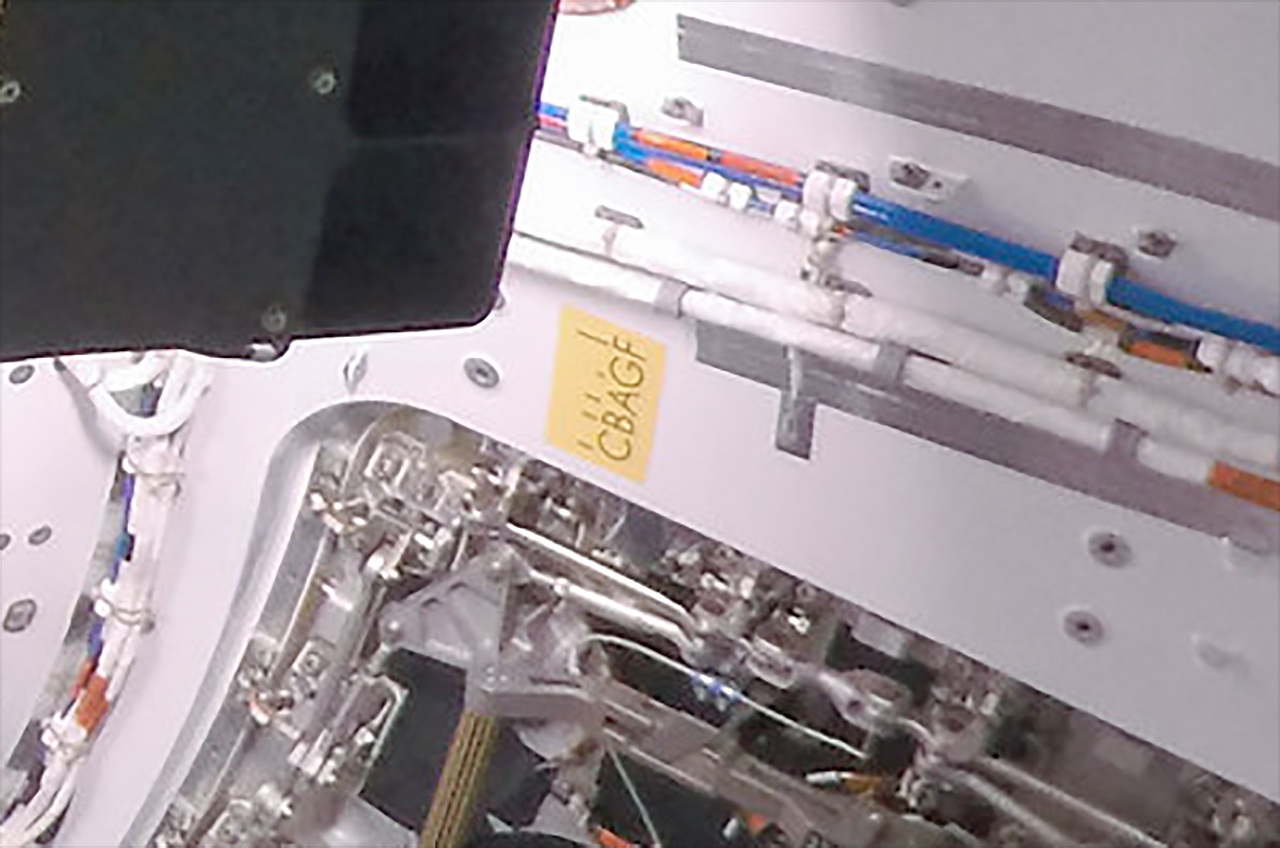

“We have five Easter eggs,” Kelly Humphries, news chief at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, confirmed in an email to collectSPACE.com. “The black and white bars between the windows, the red cardinal on the right side, the yellow sticker to the right of the hatch with ‘CBAGF,’ the black and white bars next to the NASA worm on the mass simulator (bottom right) and the numbers seen on the forward bulkhead to the right of the docking tunnel.”

The NASA and Lockheed Martin team that designed and built the Orion spacecraft for the Artemis 1 mission came up with each of the coded notes. The Exploration Ground Systems team, which prepared the ship for its launch, was the first to see the Easter eggs while installing them.

“They deciphered all the puzzles and were sworn to secrecy,” Humphries wrote.

Based on social media posts, the first of the “eggs” to be deciphered by the public was the first in Humphries’ list, the black and white bars located between Orion’s windows. The bars are Morse code — a method of encoding letters as signals that was used with the telegraph and with ham radio.

Read from the bottom up, the “dashes” and “dots” spell out “Charlie”. But who is Charlie? Was it a nod to Artemis 1 launch director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, the first woman to lead NASA’s launch control center? Was it a reference to Apollo 16 moonwalker Charlie Duke? Or maybe it was Charlie Brown, Snoopy’s owner in the Charles Schulz comic strip “Peanuts”? (An astronaut Snoopy doll was flown (opens in new tab) aboard the Orion as the Artemis 1 zero-g indicator.)

“As you can see, ‘CHARLIE’ can mean many things. For the Orion program, it commemorates Charlie Lundquist, Orion’s deputy program manager who died in 2020,” said Humphries.

A similar tribute is represented by the bird on the right side of the Orion cabin. The icon is for Mark Geyer, former Orion program manager and Johnson Space Center director — and a fan of the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team — who died in 2021.

The letters C, B, A, G, and F that appear on a yellow sticker to the right of Orion’s hatch are hidden notes of the music type. Each represents an opening note in the 1954 song “Fly Me to the Moon” written by Bart Howard. A decade later, the same song as performed by Frank Sinatra became associated with the Apollo missions to the moon.

“I think many of us were humming that song as we saw Orion perform the trans-lunar injection burn (opens in new tab),” Humphries said, adding that members of the Artemis 1 team from NASA and its international and industry partners recorded a video of them singing the same song before the mission’s launch.

The black and white bars seen next to the NASA “worm” logotype is binary for the number 18. The last mission to fly astronauts to the moon was Apollo 17, hence the next number in the sequence. (By coincidence, the Artemis I mission is set to splash down on the same date, 50 years ago, that Apollo 17 landed on the moon (opens in new tab).)

The last of the Easter eggs was the best hidden, according to Humphries. The numbers on the forward bulkhead to the right of the docking tunnel — 1, 31, 32, 33, 34, 39, 41, 43, 46, 47 and 49 — are the country calling codes for the nations that participated in building the Orion spacecraft: the United States and member states of the European Space Agency (ESA), the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, Sweden, Norway and Germany.

Related: Everything you need to know about NASA’s Artemis program

Artemis 1 is not the first NASA mission to include Easter eggs for the public to find. When the Curiosity rover began exploring Mars in 2012, its wheels left behind a track spelling out “JPL” (opens in new tab) in Morse code, a reference to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, where the mission is managed. Similarly, JPL engineers designed the descent parachute for the Perseverance Mars rover to display the lab’s motto, “Dare Mighty Things,” and its GPS coordinates in binary code.

The practice even dates back to the first time NASA went to the moon. Though not seen by the public until decades later, the MIT programmers who wrote the flight software for the Apollo 11 spacecraft included numerous Easter eggs in their 1969 source code. For example, the file name that included the machine instructions for igniting the engine was labeled “Burn Baby Burn,” while another file seemingly asked that the astronauts “please crank the silly thing around” before going “off to see the wizard.”

Whether or not Easter eggs will also become an Artemis program tradition is still to be seen, said Humphries.

“Nothing is planned at this time, but you never know if we’ll get some great ideas for future flights with crew,” he wrote.

collectSPACE.com is grateful to film and TV company Haviland Digital (opens in new tab) for supporting our Artemis 1 coverage. Their team has produced and supported titles such as the award-winning “Last Man on the Moon,” “Mission Control: The Unsung Heroes of Apollo” and “Armstrong.”

Follow collectSPACE.com (opens in new tab) on Facebook (opens in new tab) and on Twitter at @collectSPACE (opens in new tab). Copyright 2022 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.