Packed on board NASA’s Orion spacecraft, now on its way back from orbiting the moon, is a small badge representing the last mission to land astronauts on the lunar surface.

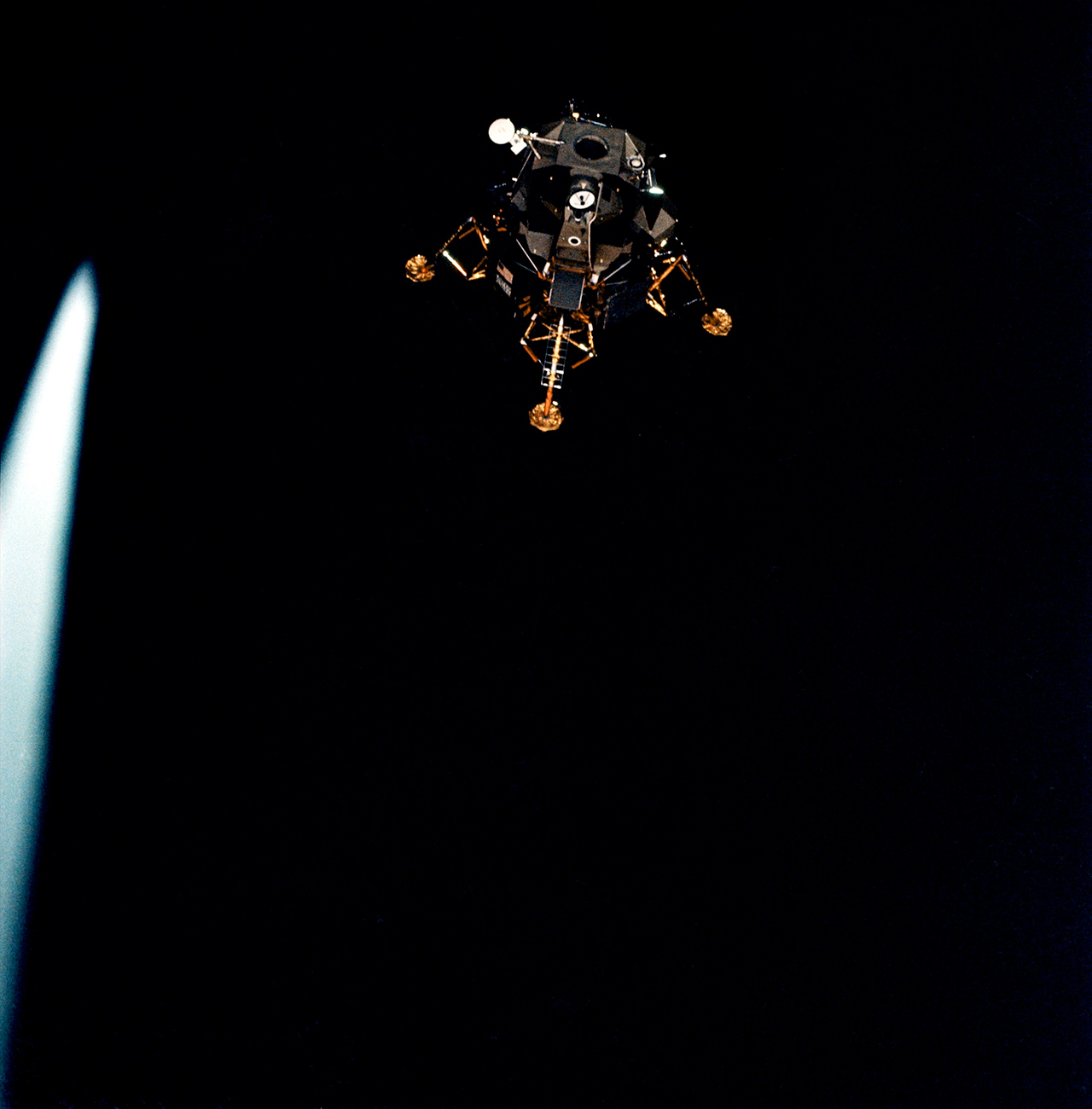

The Apollo 17 mission patch, which was flown on the uncrewed Artemis 1 capsule at the request (opens in new tab) of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, is a souvenir from the 1972 flight that saw Gene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt become the 11th and 12th humans to walk on the moon, while their crewmate Ron Evans remained in lunar orbit. It was the sixth and, to date, final time astronauts stepped foot on a world other than Earth.

The 3-inch (7.6 centimeters) emblem will arrive back on Earth on Sunday (Dec. 11), which by coincidence will be 50 years to the day since Cernan and Schmitt landed (opens in new tab) in the Taurus-Littrow valley to begin a record 75 hours on the moon.

Related: Photos from NASA’s Apollo moon missions

Orion’s reentry into Earth’s atmosphere is a critical test of the spacecraft’s heat shield. It is NASA’s top objective for the 25.5-day Artemis 1 mission to prove that the capsule is ready to return astronauts to the moon. If all goes to plan, the Artemis 2 mission will launch with a crew of four on a lunar flyby mission, followed by the Artemis 3 crew making the first human moon landing since Apollo 17.

“The current Artemis program is not without its challenges (opens in new tab); Apollo didn’t solve all those challenges. We had a different approach at the time and an approach that worked,” said Schmitt, Apollo 17’s lunar module pilot, in a NASA interview (opens in new tab) earlier this year. “Artemis needs to make sure that they’re coming up with an architecture, as they like to say, that actually will work.”

The greater challenge

With the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 17 mission coinciding with Artemis 1, the question arises: Which is (or was) the greater challenge, safely returning a new spacecraft from the moon for the first time or landing a spacecraft on the moon for the sixth?

“This is my 65th mission supporting human spaceflight, and flight testing is my jam. I love flight testing,” Mike Sarafin, NASA’s Artemis mission manager and a former space shuttle and International Space Station flight director, said during a press conference on Thursday (Dec. 8). “I would say that the first time you do anything is harder than a repeat, but that doesn’t account for new changes or objectives or harder objectives that occur on later flights.”

“It’s a difficult question to answer, because [the landing of] Apollo 17 was one of the farthest off the equator of the moon relative to the other Apollo landing sites. And the farther you got away from the equator with the Apollo architecture, it made for a much more difficult mission to accomplish,” he said.

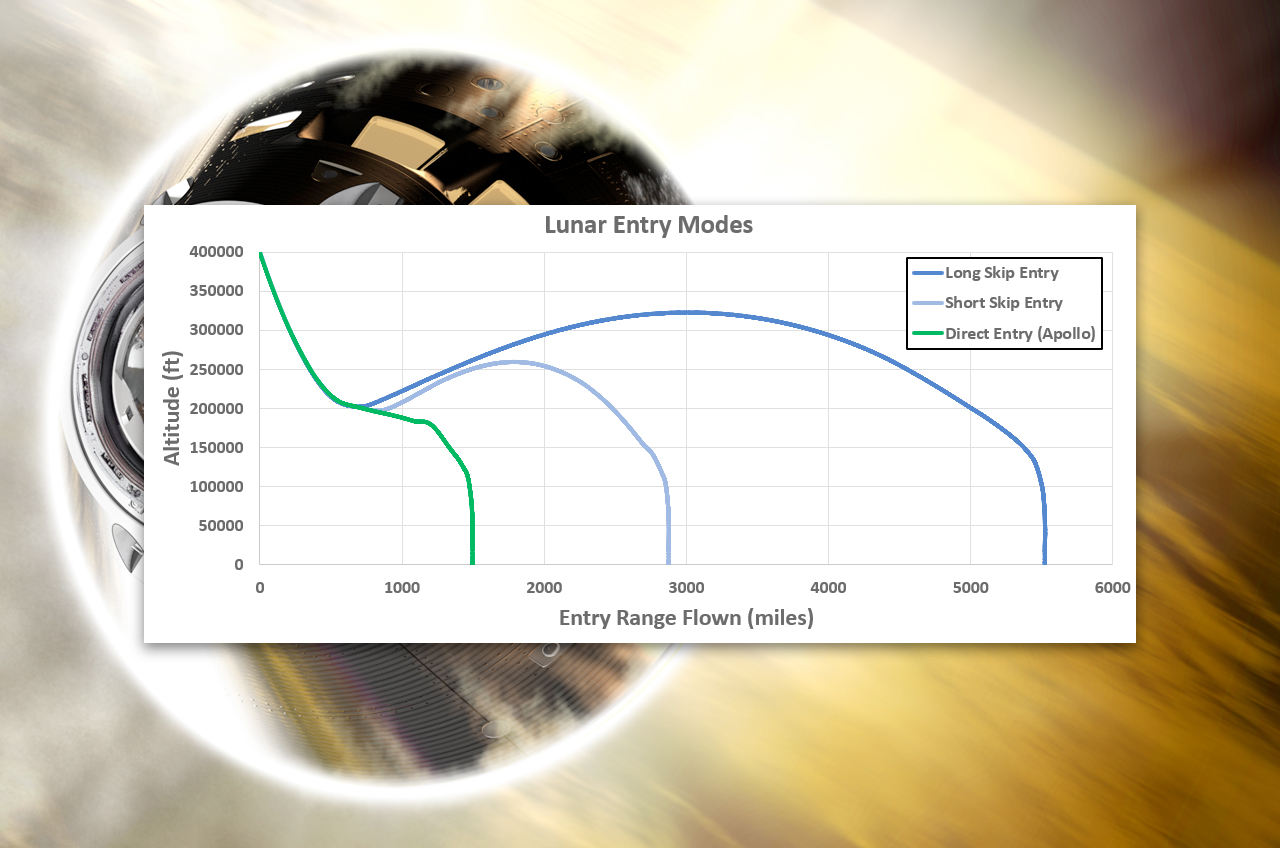

Not that the Artemis 1 mission doesn’t have its own complexities. Beyond being the first time that an Orion spacecraft has returned to Earth (opens in new tab) at lunar velocities, it will also reenter Earth’s atmosphere using a different approach than Apollo or any other human-rated spacecraft before it.

“The ‘skip reentry’ has a lower profile than a direct or ballistic reentry in the amount of deceleration that you put not only on the spacecraft, but on the passengers, the astronauts riding on board,” Sarafin said.

Like skipping a rock across a lake, Orion will dip into Earth’s upper atmosphere and use the resulting pressure, along with the lift generated by its capsule design, to skip back out. It will then plunge back into the atmosphere for its second and final descent under parachutes to a splashdown.

“Another important aspect of the skip entry is, it allows us to target a single landing site,” said Judd Frieling, entry flight director for the Artemis 1 mission. “By varying what we call the azimuth — the direction at which the crew module flies back to the target — we are always able to narrow our operations to that landing zone.”

“If you compare that to the Apollo missions (opens in new tab), where the U.S. Navy was deployed all over the Pacific Ocean, this helps both from operational and efficiency standpoints by always targeting the same spot,” he said.

Even though it is a first, Frieling and his team in Mission Control have practiced for this moment so many times they feel they can overcome any challenge thrown at them.

“We have done it so many times in practice and in failure scenarios that in many respects it feels like we’ve done this many times before,” he said. “So we expect the unexpected.”

Related: 10 strange things Artemis 1 took to the moon

Making it look easy

“Apollo made it look easy when it wasn’t,” said Michael Neufeld, a curator in the space history division of the National Air and Space Museum, in an interview with collectSPACE.com. “It looked a lot easier after they had done it six times.”

Apollo 17 may have come the closest (opens in new tab) to reaching operational status of any of the Apollo missions, but that was because the astronauts were highly trained and they also had a bit of luck that nothing seriously failed, Neufeld said. But the stakes were also different. If Artemis 1 fails, it is a setback for the program. On Apollo 17, however, lives were also at stake.

“Any moon landing was an affair requiring all the equipment to work right,” said Neufeld. “By the time of Apollo 17, the vehicle was better understood, but the mission was more challenging. They did a lot of things to try to make the landing and the challenges more feasible, but certainly it was never not dangerous at some level.”

Instead, Artemis’ greatest challenges may be what comes after it lands, as NASA seeks to resume what Apollo started but in a fewer number of steps.

“One of the notable differences between Apollo and Artemis is the maturation of technologies,” said Neufeld, referring to the four crewed Apollo missions that came before the first moon landing. “This short course [with Artemis] going from one uncrewed test to one crewed test flight around the moon, and then they are supposed to go directly to a landing? That strikes me as risky. I hope it works.”

Follow collectSPACE.com (opens in new tab) on Facebook (opens in new tab) and on Twitter at @collectSPACE (opens in new tab). Copyright 2022 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.