NASA’s Artemis moon program is not a reboot of Apollo-era technology. The agency has built a new rocket and spacecraft to get astronauts to Earth’s nearest neighbor, and it’s developing a new toolkit for them to use on the lunar surface as well.

While the tried and true geologist’s hammer remains on tap, fresh capabilities are being appraised to sharpen astronauts’ next look-see on the moon with first-time equipment.

Adam Naids is the deputy project manager for Artemis geology tools at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston. He and colleagues are digging into gear that could help astronauts meet challenges faced during Apollo but are also user-friendly.

Related: Facts about NASA’s Artemis 1 moon mission

Last June, Naids noted, it was announced that NASA has partnered with industry for new spacewalking and moonwalking services. Among the duties outlined under that Exploration Extravehicular Activity Services (xEVAS) contract, Axiom Space and Collins Aerospace are to hone Artemis spacewalking systems for use on the lunar surface and to help prepare for human missions to Mars.

“There are a lot of things that have to come together to get humans on the moon,” Naids told Space.com. For example, that ambitious effort will rely on, among other hardware, NASA’s huge new Space Launch System rocket, Orion capsule, privately developed crewed lunar landers and new spacesuits.

“We did a lot of research and deep diving into what Apollo did,” Naids said.

Vacuum-sealed containers

There has already been some invention along the way. For instance, engineers are working to make specialized mechanisms that are well suited to work in the harsh lunar environment, Naids said. Given that Artemis aims to set up a crewed outpost near the moon’s south pole, capturing material that is frozen in the lunar regolith has received special attention.

“It doesn’t take a lot to turn those frozen samples from a solid to a gas, so we developed vacuum-sealed containers that have a metal-on-metal seal. That is a very complicated mechanism, but critical as one of the fundamental goals of Artemis is to bring back those samples,” Naids said.

Artemis team members are also developing a tool belt, he added. The belt will connect to the future spacesuit and comes complete with two separate swing arms, one on each side, that can be set out or put back into position. It is meant to give an astronaut access to a variety of tools. “It’s basically a platform [through] which the crewmember can access most things themselves,” Naids said.

The tool belt will provide the wearer the ability and agility to go off and explore by themselves, to collect lunar specimens without aid from another moonwalker.

Meanwhile, Apollo-era lunar tools such as tongs, rakes, scoops, extension handles, and sample bags worked well decades ago and could in the future as well. “There’s a lot of history there,” Naids said.

Related: NASA picks spacesuit maker for 1st Artemis moonwalkers

Dust-tolerant technology

One clear message from Apollo was the need to deal with troublesome lunar dust, which is sticky, spiky and pervasive, posing a potential threat to sensitive equipment.

“It’s definitely of major concern and a challenge. It gets on everything,” Naids advised. “I don’t think we’ll ever create tools that are ‘dust free.’ We’ve been using the terminology of ‘dust tolerant.'”

At JSC, lunar simulants that mimic moon dust have been used to test how envisioned equipment and procedures would hold up in the lunar environment. Similarly, astronauts have put to the test moon-bound gear in the space agency’s huge swimming pool-like neutral buoyancy tank.

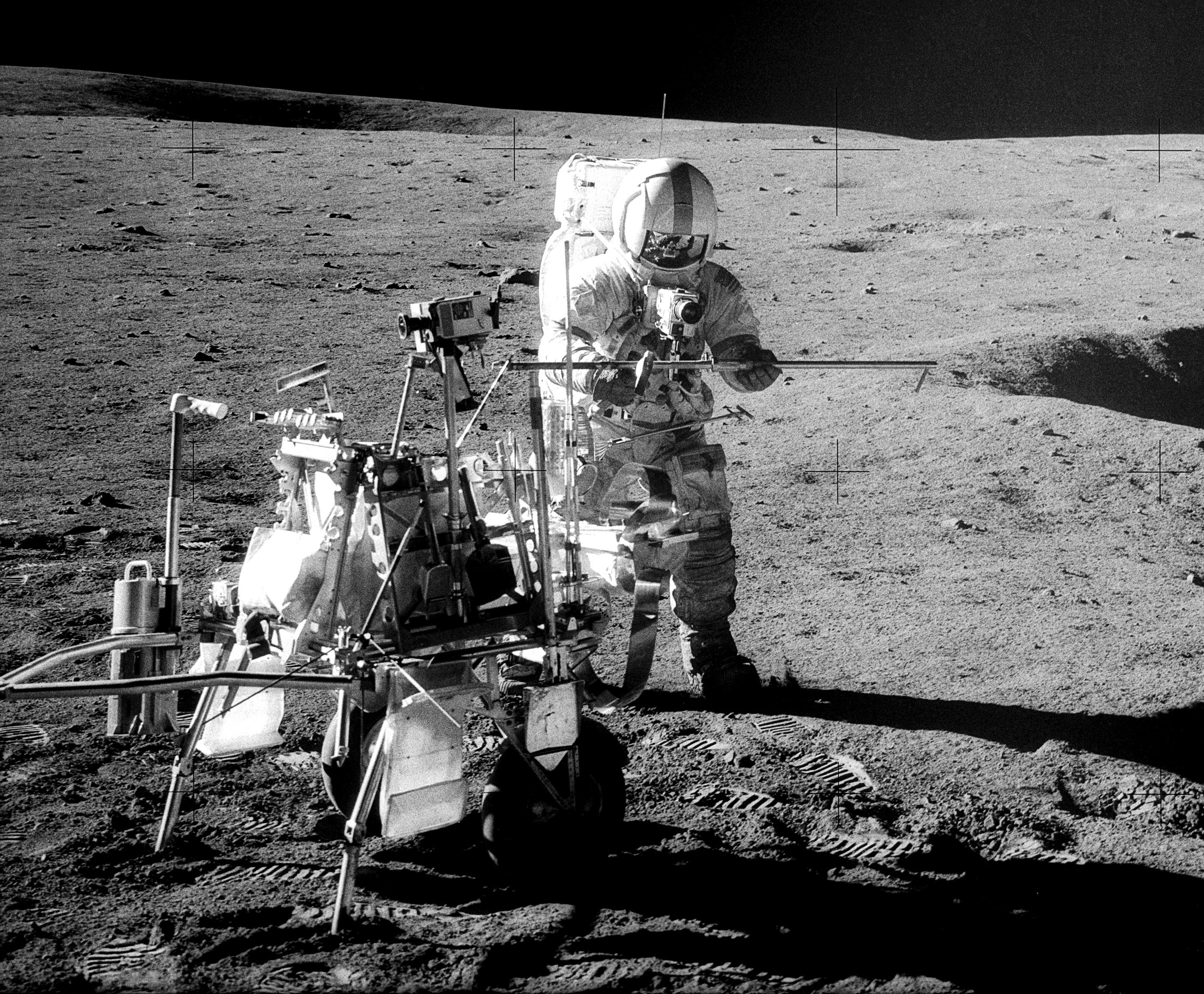

The Apollo moonwalkers did encounter hardware woes, Naids added. It was tough to drill into the moon, for one. Understanding the soil and whether it’s going to be harder to chew through at the south pole than at the equator is a matter of concern.

And some Apollo equipment didn’t work as well as hoped on the lunar surface. Take the rickshaw hand cart of Apollo 14 —the Modular Equipment Transporter, or MET for short.

“It was hard to maneuver. In one-sixth gravity, it was so light that if it hit something it would fly off the surface. Eventually, the crew members were carrying it,” said Naids.

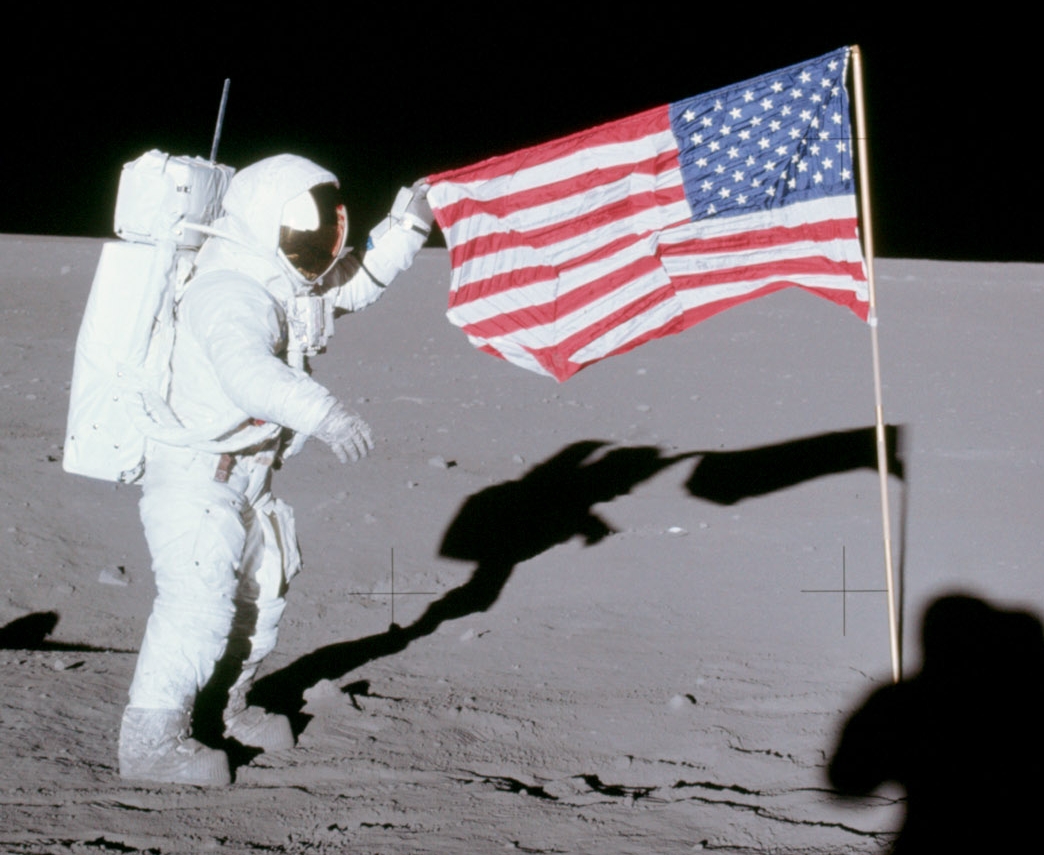

Another item that has been looked into is a flag strategy. “We looked into what they did on Apollo in terms of sizes, how they hammered the flag into the ground, and how we can make the flag last longer,” Naids said. If crews are going back to the same lunar locale a couple of times, setting up a flag must account for the harsh ultraviolet radiation on the moon that can bleach a flag white, he said.

Related: Great photos from NASA’s Apollo moon missions

New outerware

Artemis crewmembers may also sport new forms of outerwear. Because of the conditions at the lunar south pole — stark lighting conditions and extreme cold in the shadows of crater walls — navigation and direction-finding support may be high priorities.

NASA has already begun testing some such gear in the Arizona desert. One of the items that has been assessed is a wearable kinematics system, designed by Draper Labs in Cambridge, Massachusetts, that enables the wearer to map their environment, track their position and orientation, as well as monitor their time on task.

Draper’s field tests in Arizona were conducted as part of NASA’s Joint Extravehicular Activity Test Team Field Test #3. Held last October, the outing focused on duties that may be performed by Artemis 3 astronauts. Artemis 3, the first Artemis mission to the lunar surface, is scheduled to launch astronauts toward the south polar region in 2025 or 2026.

Heads-up displays

Also reflecting on Apollo tool handling is James Head, a professor of planetary geosciences at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Back in the day, he helped select where Apollo landers would touch down on the moon, taught geology to moonwalkers and how to study the samples they brought back.

For Head, the key question is, What is the nature of new tools that increase the ability of astronauts on the surface to optimize their exploration capabilities? He thinks there’s a need for critical heads-up displays that will help Artemis crews navigate and optimize sample collection near the moon’s south pole.

“This is in contrast to the International Space Station general approach, which is to make the tools and then to be available to walk the astronaut through procedures from the Mission Operations Control Room,” Head told Space.com.

Briefings and debriefings

Vital to upcoming lunar exploration, Head said, will be gathering data on Earth that can be used for traverse planning updates — where to go and what to do on coming moonwalks.

“Debriefing/briefings between moonwalks will be critical, and this will be a major responsibility of the ‘back room,’ as in Apollo. And this training, for both the astronauts and the back room, is required for Mars, where there will be no real-time communication, and the astronauts will be on their own during surface exploration, as in Apollo, with the absolutely best situational awareness,” Head emphasized.

Head also said that a critical element of Artemis crew exploration will be human/robotic partnerships. Robotic rovers will explore, interpolate and extrapolate, gathering data that will be sent directly to mission control to feed into contingency and preplanning of the next human lunar surface traverse.

Up-mass issue

“Some of the tools can definitely be used to optimize the selection of samples in real time. New and updated Artemis hand-held remote sensing tools for geochemistry and mineralogy need to be optimized and design-assisted in field training,” said Head.

But Head also underscored the bottom line for Artemis expeditions returning precious lunar samples back to Earth.

“Remember that the Artemis sample return up-mass is about 50 kilograms, roughly 110 pounds, a value significantly exceeded by the last three Apollo missions 50 years ago,” Head said. The quest for “better tools” is not an excuse to get around this constraint in hauling samples back to Earth, he said.

Testing is ramping up

For the time being, on-Earth appraisal of Artemis moonbound gear is ongoing and the pace of testing is increasing.

“I am confident that, this time around, it’ll be much easier for the crewmembers,” NASA’s Naids said. “We’re keeping things the same where it makes sense. We’re changing the things that got feedback.”

But at the end of the day, lunar conditions — a vacuum environment, omnipresent dust, microgravity, night and day temperature swings and high radiation levels, for example — are tough to replicate here on Earth.

“It’s very hard to simulate the entire lunar environment here on the ground. Some things make it harder than it would be on the moon,” concluded Naids. “It will be exciting to see that all come together.”

Leonard David is author of the book “Moon Rush: The New Space Race (opens in new tab),” published by National Geographic in May 2019. A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades.Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).