Within an office complex along the Dutch coast lies an artificial star.

It isn’t an actual star. The complex is the European Space Agency‘s (ESA) European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC), and its artificial star consists of a rotating table before a point of light that simulates the color and brightness of a given star. Engineers use this room to test star trackers.

Staring out into the cosmos, it is easy for both humans and hardware to lose their bearings. The stars can come to their aid. Just as humans have long used the stars to navigate themselves, satellites and other spacecraft often judge their position with star trackers.

Related: What is a satellite?

There are many models of star trackers. But a typical star tracker captures the sky with a camera or another light-catching device. Then, the star tracker might reference its sight against a catalogue of known, bright stars to reconstruct position. Electronic star trackers have existed since the 1950s, and all sorts of gadgets from guided missiles to ground telescope Goto mounts use them.

But star trackers’ most prominent users are satellites. Satellite star trackers range from low-cost open-source star trackers intended for cubesats to cutting-edge devices like ASTRO XP, which can autonomously keep satellites aligned to within 0.1 arcsecond of sky and will be used on future ESA missions like the ATHENA X-ray telescope and LISA gravitational wave observatory.

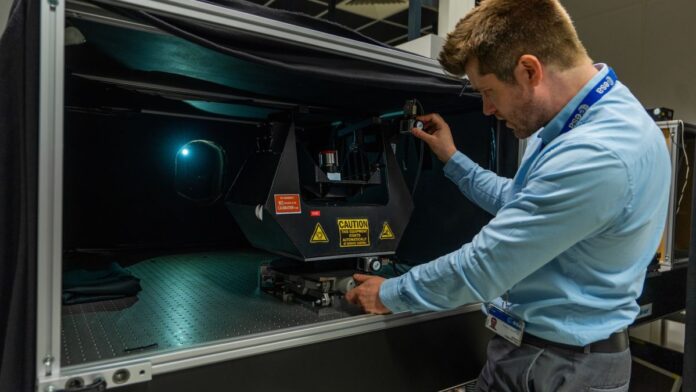

Of course, the builders of star trackers need to actually test their tools before launching them aboard satellites. And that’s where star simulators — like the one featured in the photo above, in ESTEC’s GNC, AOC and Pointing Laboratory — come in handy.