Less than a month after astronomers found satellite trails scarring many images snapped by the Hubble Space Telescope, a new paper is urging scientists to “fight tooth and nail” to protect the night sky against rising light pollution.

“We are very pessimistic about the path being followed by an important part of the scientific community (and other actors) that works on and has responsibilities for these areas of research,” the authors wrote in the paper (opens in new tab), which was published Monday (March 20) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The new paper, a comment article, argues that current efforts by astronomers are mitigating the problem of light pollution in astronomy but will not solve it unless strict and immediate regulations are enforced.

Related: Challenge for astronomy: Megaconstellations becoming the new light pollution

Light pollution caused by artificial urban lighting on Earth, as well as satellites congesting low Earth orbit, has been hampering astronomical observations since at least 1957 (opens in new tab). For over six decades, astronomers have repeatedly voiced concerns that the observations made by ground-based telescopes, which are the workhorses of space science, have become increasingly damaged.

Much of the blame is placed on light-emitting diodes (LEDs), which were once thought to be an efficient solution to save energy and money because they focus light on a specific area, but were soon revealed to actually worsen light pollution (opens in new tab). For example, an LED lamp post with a lifespan of 100,000 hours will last for 24 years — four times longer than sodium lamps that were previously dominant, according to the latest paper.

To get as far as possible from urban lighting, scientists have built observatories in remote areas not yet suffering from high light pollution. However, Earth has only so many such locations, and “there are almost no more remote places available on Earth that simultaneously meet all the characteristics needed to install an observatory,” according to the article.

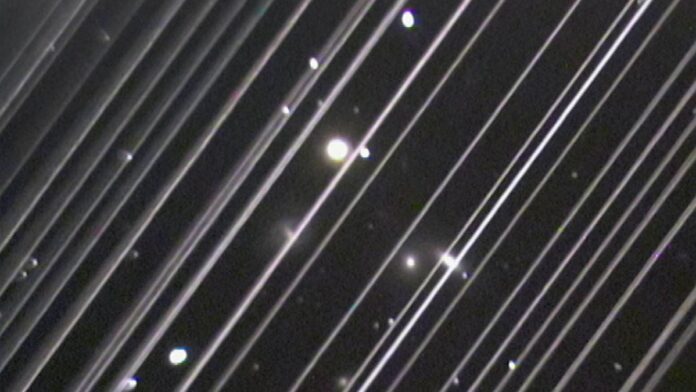

Space telescopes in low Earth orbit face a similar problem. Earlier this month, a team of citizen scientists found that over 5% of recent Hubble Space Telescope images were streaked by SpaceX’s Starlink satellites. Starlink is the company’s broadband megaconstellation, which consists of more than 3,700 operational satellites at the moment — and that number is growing all the time. In addition, other companies, such as Amazon, plan to build megaconstellations of their own in the near future.

Astronomers have been vocal about the impact of light pollution on astronomy ever since artificial satellites became more than a minor nuisance for competitive and expensive telescope observations. When SpaceX launched its first batch of Starlink satellites, amateur and professional astronomers alike were quick to point out the surprising brightness of the satellites, whose bodies and solar panels can reflect sunlight and become bright enough to be seen even by the unaided eye. Over the years, astronomers have closed the shutters of telescopes when satellites drift into view and sometimes pointed them toward rare pockets of the sky lacking satellites.

Earlier this year, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and SpaceX agreed to reduce satellite interference on radio astronomy. Such agreements, however, are merely mitigation strategies that would ultimately not solve the problem, according to the comment article. The authors call on the scientific community to do more and demand stricter regulation, stating that any hopes for the space economy to limit itself unless forced to do so is “naive to hope.”

Instead, the authors propose tightening the criteria to authorize massive satellite constellations and enforcing an upper limit for the number of orbiting satellites and the amount of artificial light produced. When the limit is reached, regulatory standards such as deorbiting old satellites before allowing new ones into orbit must be enacted, the authors say. “Despite the popularity of satellite megaconstellations, we must not reject the possibility of banning them,” as the risks to the night sky are too high, according to the paper.

The authors place the responsibility of advocating for such regulations on the shoulders of scientists, who are in “an optimum position,” thanks to active personal and professional collaborations across the world.

“Now is the time to consider the prohibition of megaconstellations and to promote a significant reduction in [artificial light at night],” the authors say. “Our world definitely needs a ‘new deal’ for the night.”

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @Sharmilakg (opens in new tab). Follow us @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab), or on Facebook (opens in new tab) and Instagram (opens in new tab).