Astronomers have been on the hunt for the origins of Furbies. No, not the eerie little toy creatures, but Fast Radio Bursts, or FRBs (often pronounced “fur-bees”). These FRBs are mysterious pulses of radio waves coming from space, and what exactly causes them is yet to be determined.

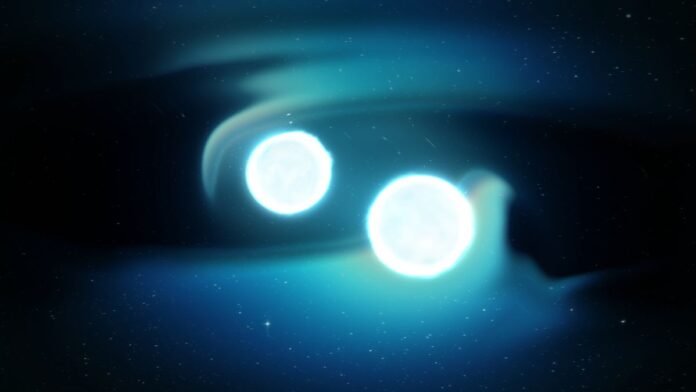

New observations suggest that fast radio bursts may actually be linked to another hot topic in astronomy: Neutron star mergers, the collision of the leftover cores from two massive stars that produce ripples in space time known as gravitational waves.

The evidence for this connection comes from a curious coincidence. A gravitational wave event known as GW190425 was detected by the famed Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in April 2019 only two and a half hours before a Canadian radio telescope spotted a powerful FRB in the same patch of sky. The researchers calculate a less than 1% chance that this was truly a coincidence, where the events were not really related to each other.

“This is extremely exciting and would certainly help unravel some of the mystery surrounding these fast radio bursts,” Alexandra Moroianu, an astrophysicist at the University of Western Australia and lead author on the study, said in a statement (opens in new tab).

Related: Mysterious fast radio bursts could reveal hidden matter around galaxies

FRBs are very short pulses of radio waves, observed with radio telescopes. Some happen again and again, and some are one-off flares. Repeating FRBs (those whose signals keep coming back again and again) are thought to come from magnetars, neutron stars with extreme magnetic fields — but the one-offs remain a mystery.

Scientists don’t know what neutron star mergers and non-repeating FRBs have in common. The authors of the new study propose that these two phenomena may be two steps in the same process.

When two neutron stars collide, they may form a rapidly spinning, even bigger neutron star that only lasts for a short time, the researchers think. That neutron star is unstable, and will soon collapse down into a black hole — and it might create the FRB when it does so. The observation of gravitational waves, which are a clear sign of a neutron star merger, coincident with an FRB is not definitive proof that this is what’s happening, but it does hint at this connection.

“An association like this one is not completely unexpected,” Bing Zhang (opens in new tab), study co-author and astrophysicist at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, said in the statement.

“Given the chance probability statistics, I wouldn’t definitively confirm the association just yet,” said Zhang. “At the same time, though, the potential association presented in this work definitely calls for closer scrutiny of future GW–FRB associations.”

This research was recently published in Nature Astronomy (opens in new tab).

Follow the author at @briles_34 (opens in new tab) on Twitter. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).