NASA is just days away from slamming a spacecraft into an asteroid 7 million miles (11 million kilometers) from Earth.

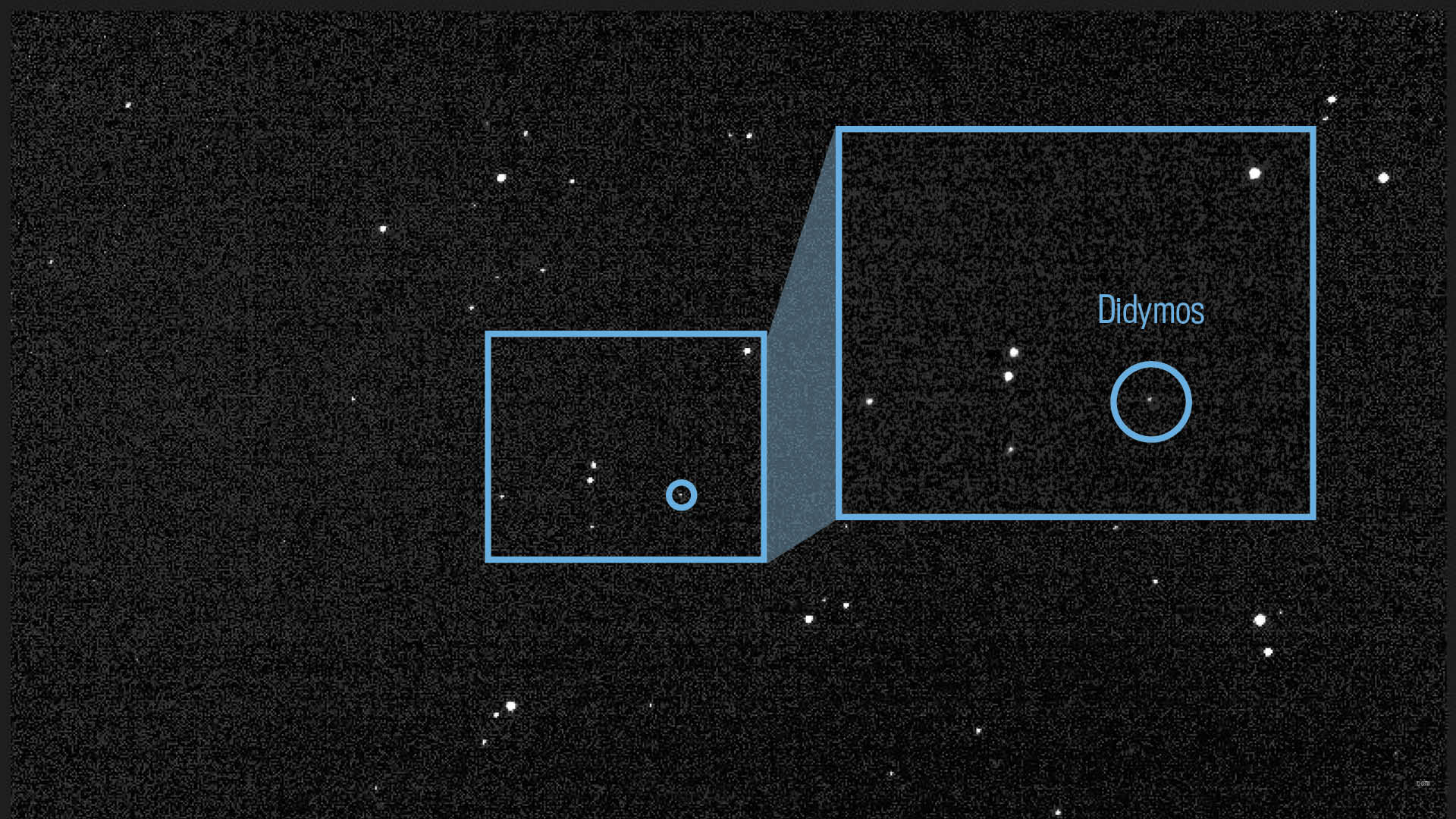

The agency’s long-awaited Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission will impact with the asteroid moonlet Dimorphos on Monday (Sept. 26), if all goes according to plan. The DART mission launched on Nov. 23, 2021 on top of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and is now hurtling through deep space toward the binary near-Earth asteroid (65803) Didymos and its moonlet Dimorphos.

The mission, which is managed by the John Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL), is humanity’s first attempt to determine if we could alter the course of an asteroid, a feat that might one day be required to save human civilization. While changing the orbit of an asteroid 7 million miles away sounds daunting, DART team members from NASA and JHUAPL said during a media briefing on Thursday (Sept. 22) that they are confident that the years of planning that have gone into the mission will lead to success.

Related: NASA’s DART asteroid-impact mission will be a key test of planetary defense

Traveling at speeds of 4.1 miles per second (6.6 km/s), or 14,760 mph (23,760 kph), the DART spacecraft will impact the 560-foot-wide (170 meters) Dimorphos, a moonlet that orbits the other member of its binary system, the 2,600-foot-wide (780 m) asteroid Didymos.

Doing so, NASA believes, will shift Dimorphos’ orbital period enough to alter its gravitational effects on the larger Didymos, changing the trajectory of the pair.

Katherine Calvin, chief scientist and senior climate advisor at NASA, said that while DART will be a key test of this “kinetic impactor” planetary defense strategy, the mission will also produce valuable science that will allow astronomers to peer back into the deep history of the solar system.

“We’re looking at asteroids to make sure that we don’t find ourselves in their path. We also study asteroids to learn more about the formation and history of our solar system. Every time we see an asteroid, we’re catching a glimpse of a fossil of the early solar system,” Calvin said.

“These remnants capture a time when planets like Earth were forming,” she added. “Asteroids and other small bodies also delivered water, other ingredients of life to Earth as it was maturing. We’re studying these to learn more about the history of our solar system.”

Lindley Johnson, planetary defense officer at NASA, said that DART marks a turning point in the history of the human species.

“This is an exciting time, not only for the agency, but for space history and the history of humankind,” Johnson said during Thursday’s briefing. “It’s quite frankly the first time that we are able to demonstrate that we have not only the knowledge of the hazards posed by these asteroids and comets that are left over from the formation of the solar system, but also have the technology that we could deflect one from a course inbound to impact the Earth. So this demonstration is extremely important to our future.”

That sentiment was echoed by Tom Statler, a DART program scientist at NASA. “The first test is a test of our ability to build an autonomously guided spacecraft that will actually achieve the kinetic impact on the asteroid. The second test is a test of how the actual asteroid responds to the kinetic impact,” Statler said. “Because, at the end of the day, the real question is: How effectively did we move the asteroid, and can this technique of kinetic impact be used in the future if we ever needed to?”

Read more: DART asteroid mission: NASA’s first planetary defense spacecraft

The outcome of the DART mission on Monday (Sept. 26) will certainly help answer that question, and many of the DART team members shared their confidence in the mission during the briefing. Edward Reynolds, DART project manager at JHUAPL, said the spacecraft is ready to smash itself to pieces on the surface of Dimorphos when the time comes.

“What we can say at this point is that all subsystems on the spacecraft are green, they’re healthy, they’re performing very well. We have plenty of propellant and we have plenty of power,” Reynolds said. “We’ve been doing a bunch of rehearsals, and some of the rehearsals are very nominal.”

“At this point, I can say that the team is ready,” Reynolds added. “The ground systems are ready, and the spacecraft is healthy and on track for an impact on Monday.”

Engineers on the DART team are watching the spacecraft’s trajectory carefully over the coming days leading up to the impact, which should occur at 7:14 p.m. EDT (2314 GMT) on Monday (Sept. 26). Elena Adams, DART mission systems engineer at JHUAPL, said that the team is still making sure the impactor spacecraft is on course.

“Over the next couple of days, we’re actually still performing some trajectory correction maneuvers to make sure that we are on the right path to hit the asteroid,” Adams said. “We rehearsed a lot. But as we go through the cruise phase, we update parameters in the spacecraft to make sure that we can actually hit the asteroid. And so in the last couple of days, we’ll update those parameters; we’ll do checks like streaming images back to Earth.”

“So in the next few days, we’ll take more images of the Didymos system, we’ll do trajectory correction maneuvers, and then at 24 hours prior to impact, it’s all hands on deck,” she added.

Adams said the team has 21 contingencies in place in case DART’s Small-body Maneuvering Autonomous Real Time Navigation (Smart Nav) system determines that the spacecraft is off course. “We’ve planned for all the things, and we’re ready to intervene. And we have been rehearsing this for quite some time.”

The 21st contingency the team has planned for is DART’s survival. In the event that DART misses Dimorphos, Adams says the team will immediately begin processing the data the spacecraft collected and plan for a possible impact with other objects.

“We’re going to sit down back into our seats and we’re going to start preserving all the data on board if it misses. And we’ll have time with our Deep Space Network right afterwards to be able to actually get all that data down,” Adams said. “And then we’ll start conserving propellant and we’ll start looking for [other] objects to come back to.”

In response to a question from Space.com concerning any flight testing the team has conducted, Adams mentioned a recent set of images the DART spacecraft’s DRACO camera took of Jupiter and its four big Galilean moons. The DART team captured the images in order to “fool” the DART spacecraft’s SMART Nav system so that its tracking capabilities could be tested.

“We actually watched Europa exit from behind Jupiter. And we fooled our Smart Nav that Jupiter was Didymos and Europa was Dimorphos, and we actually watched the separation happen,” Adams said.

That’s important, she added, “because in the last four hours during our terminal phase, when the spacecraft is completely autonomous, we’re going to watch Dimorphos emerge from behind Didymos. So, we already trained the system to do this in flight. So we’re looking forward to it. I think we can do it.”

Statler reiterated that confidence, adding that, while this type of mission was once the stuff of fantasy, the DART team believes we now have the tools and the knowledge to carry out a successful planetary defense mission.

“We’re moving an asteroid. We are changing the motion of a natural celestial body in space,” Statler said. “Humanity has never done that before. And this is the stuff of science fiction books, and really corny episodes of ‘Star Trek’ from when I was a kid. And now it’s real. And that’s kind of astonishing that we are actually doing that and what that bodes for the future: What we can do, as well as our discussions of what humanity should do.

“It opens up an amazing frontier,” he added. “It’s very exciting.”

Follow Brett on Twitter at @bretttingley (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).