During the next week or so, keep a sharp eye on the night sky for the possibility of catching sight of an outstandingly bright meteor, for there’s a chance that Earth will encounter a swarm of unusually large particles capable of generating some eye-catching really brilliant fireballs, the kind that make the unsuspecting public call the police.

Every year about this time, the Earth passes through a broad stream of debris left by the periodic comet Encke. The dusty material associated with this comet hits the Earth’s atmosphere at approximately 19 miles (30 km) per second and burns up, creating the Taurid meteor shower.

The 2022 version of the Taurids conceivably could turn out to be especially bright and put on an eye-catching show. But also, this year, unfortunately, these meteors will run up against some significant competition in the form of a full, or nearly full moon, which on most nights will light up the sky and likely will squelch most of the fainter streaks.

Related: Taurid meteor shower 2022: When, where & how to see it

The Taurids are actually one of the year’s longest with some recognizable activity (at least a couple of shower members per hour) with their first forerunners appearing around Oct. 20th and their last stragglers disappearing around Nov. 30th. But it is during a one-week time frame extending from Nov. 5th through Nov. 12 when the Taurids are most active.

During this timeframe, about five to 15 meteors may be seen per hour by a single observer with clear, dark skies (city lights or even a slight haze will reduce substantially the number of faint meteors seen). These meteors are often yellowish-orange and, as meteors go, appear to move rather slowly.

We’ll come back and discuss this handicap a bit later. But first, let’s talk about the characteristics of the Taurid meteors.

Larger meteoroids expected this year

Meteors — popularly known as “shooting stars” — are produced when debris about the size of pinheads and sand grains enters and burns up in Earth’s atmosphere. In the case of the Taurids, they are attributed to debris left behind by comet Encke or perhaps by a much larger comet that upon disintegrating, left Encke and a lot of other rubble in its wake.

Indeed, Comet Encke is thought by some astronomers to be a piece of a huge comet that broke up 20,000 to 30,000 years ago. These comet break-ups are often caused by gravitational encounters with Earth or other planets. This supposed break-up may explain why there are so many Encke-like pieces moving around the inner solar system. In 1982, two British astronomers, S. V. M (Victor) Clube and William Napier, even postulated that it was a huge fragment of comet Encke’s parent that produced a 5-megaton explosion over Tunguska, Siberia in June 1908.

Known as the Taurid Swarm, these bright meteors are created when the Earth runs into a group of pea and pebble-sized fragments from the comet that then burn up in the atmosphere

Encke has the shortest known orbital period for a comet, taking only 3.3 years to make one complete trip around the sun. Meteor expert David Asher discovered that the Earth can periodically encounter swarms of larger particles shed by this comet (opens in new tab) in certain years and 2022 is predicted to be one of those years.

Two streams for the price of one

The Taurids are actually divided into two different showers: the Northern Taurids and the Southern Taurids. This is an example of what happens to an elderly meteor stream. Even at the beginning, the particles could not have been moving in exactly the same orbit as their parent comet; their slight divergence accumulates with time. The sun is not the only body gravitationally controlling the particles’ orbits; the planets are also having subtle effects on the stream. As the positions of the planets are constantly changing, the particles pass nearer to them on some revolutions than others — diverting parts of the stream, fanning it out and splitting it.

So, what was originally one stream diffuses into a cloud of minor streams and isolated particles in individual orbits, crossing Earth’s orbit at yet more widely scattered times of the year and coming from more scattered directions until they are entirely stirred into the general haze of dust in the solar system. Because this has been going on for tens of thousands of years, visible meteors from these streams are active not for several days or even a week or two, but for up to six weeks or more.

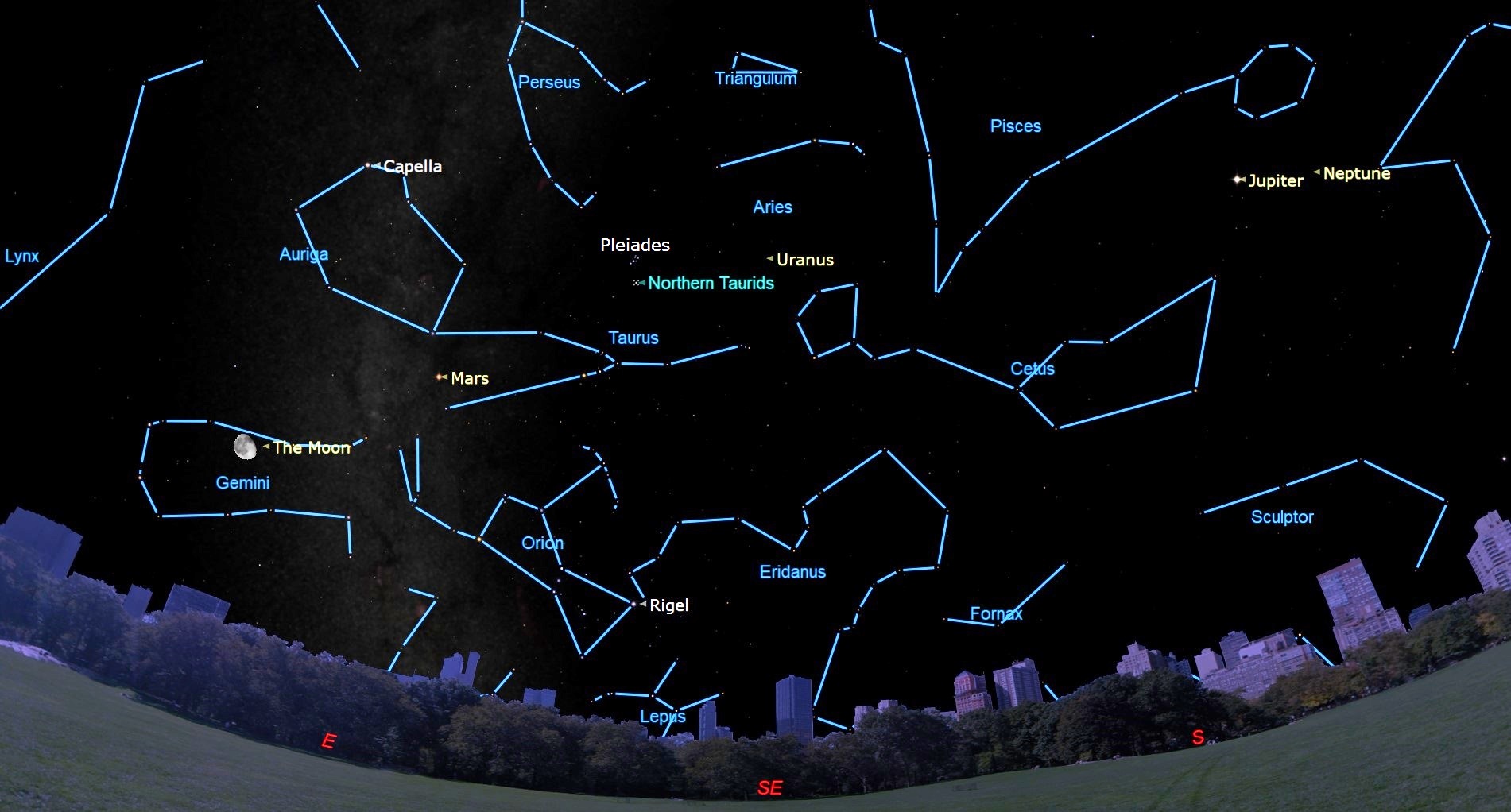

The radiant of a meteor shower is the point in the sky, from which meteors appear to originate. But as we already have noted, the Taurid radiant is double with the southern radiant most active on Nov. 5th and the northern radiant most active on Nov. 12th. Both cross the southern meridian and are highest in the sky about 12:30 a.m. These two radiants lie just south of the famous Pleiades star cluster. After 12:30 a.m., they will be descending the western sky.

So, during the next week or so, if you see a bright, slightly tinted orange meteor sliding rather lazily away from that famous little smudge of stars, there’s a very good chance you’ve sighted a Taurid.

Moon muscles in…

Now for the bad news. As we alluded to earlier, the timing is poor so far as the phase of the moon is concerned. This year’s Taurids are expected to be most prolific between Nov. 5 and Nov. 12.

And right in the middle of this time frame, on the night of Nov. 7 into the early hours of Nov. 8, the moon will turn full and light up the sky like a giant spotlight. The best way to combat the bright moonlight is to try and do your meteor observing this upcoming weekend, when the moon is below the horizon. Moonset on Saturday morning, Nov. 5th, comes at around 4:15 a.m. local daylight time. Dawn breaks at around 6 a.m. So, the sky will be dark and moon-free for about 105 minutes.

Remember to turn your clocks back at 2 a.m. on Sunday morning, Nov. 6, as we return to standard time; moonset that morning will come at about 4:25 a.m. local standard time. Dawn breaks about 35 minutes later, so your dark sky time will be much shorter.

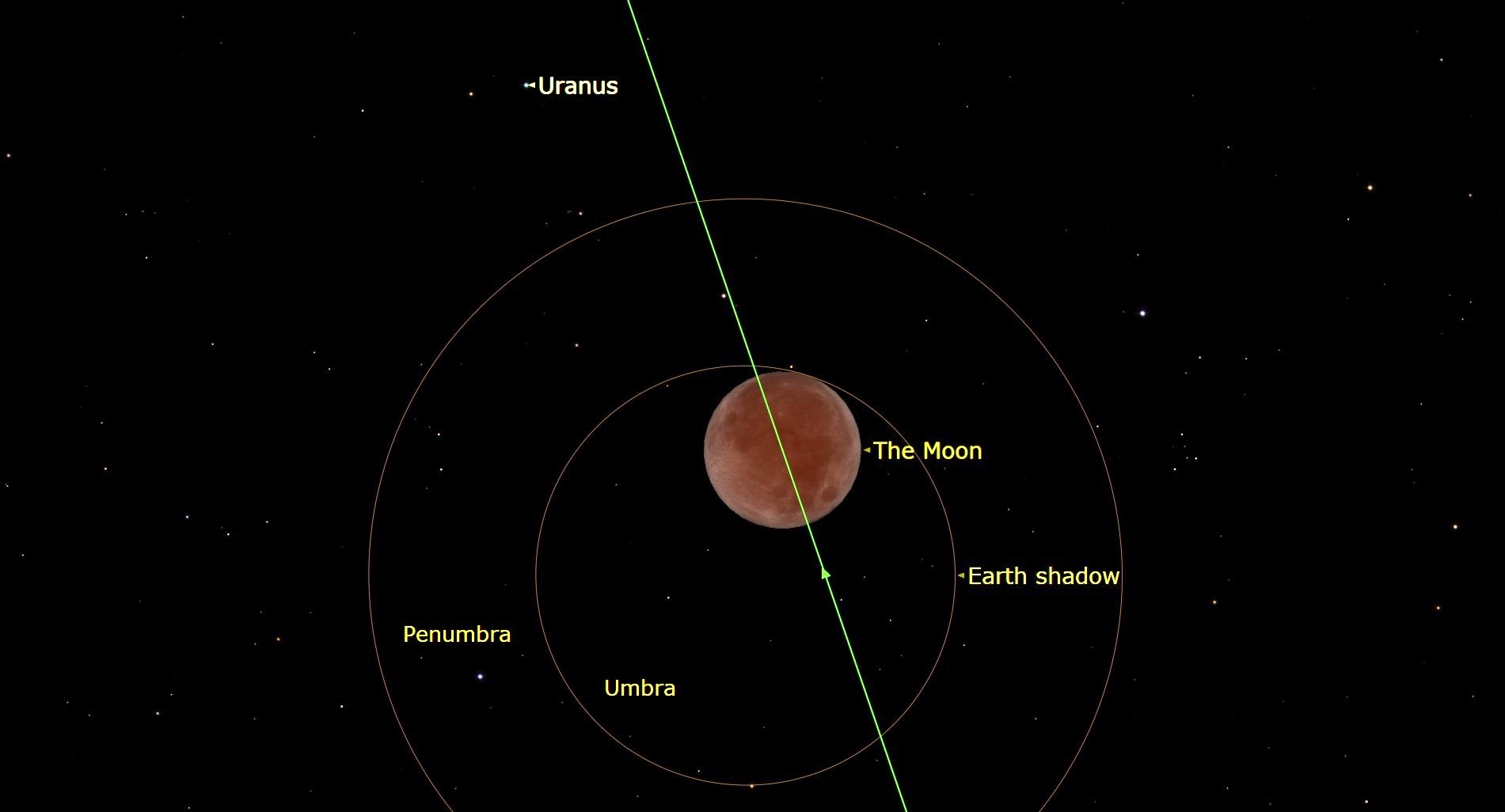

However, the lunar eclipse will help

But wait! There will be some dark sky time on the night of full moon because of a very special circumstance: For during the morning hours of Tuesday, Nov. 8, the full moon will undergo a total lunar eclipse as it passes completely into the Earth’s shadow. Totality will last 85 minutes and during that time, the moon will be reduced to at least 1/10,000 its normal brightness compared to just prior to the start of the eclipse. So, take advantage during the total phase and carefully scan the sky for some possible bright Taurid meteors.

Read more: Beaver Blood Moon lunar eclipse 2022: Everything you need to know

2005 redux?

The year 2005 was an exceptional year for the Taurid Swarm (opens in new tab) as many stupendously bright meteors were seen when fireballs as bright as the full moon were witnessed. The branding of “the Halloween fireballs” for Encke’s spawn seems to date from that return.

Will 2022 offer a repeat performance? All expectations come from the usual caveat: meteor showers have a way of fooling everyone. Only by going out and watching for these colorful and slow-moving meteors will we know for sure!

Good luck and clear skies!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium (opens in new tab). He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine (opens in new tab), the Farmers’ Almanac (opens in new tab) and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).