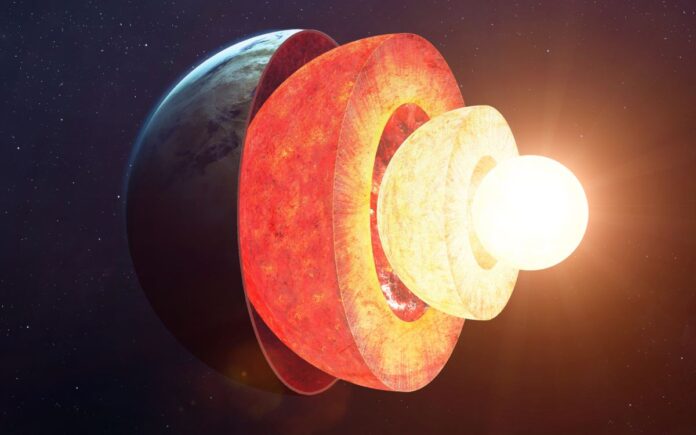

Except for the thin crust we live on, Earth’s structure is intangible deep beneath our feet, and as a result hard to imagine.

Foods are often used to demonstrate how Earth is made of four main layers, metaphors that call to mind a tasty snack (opens in new tab): graham crackers for the crust, ice cream for the mantle, melted marshmallows for the outer core and chocolate chips for the inner core.

Scientists have long known about a fifth layer: a 400-mile-wide (650 kilometers) metallic ball inside the inner core, fittingly named as the innermost inner core. Since it was first theorized (opens in new tab) in 2002, scientists have confirmed (opens in new tab) its presence multiple times (opens in new tab), most recently in March 2022 (opens in new tab). However, because it is hidden under Earth’s various layers and lies deep inside the planet’s inner core — which itself is less than 1% of Earth’s volume — the innermost inner core is not well understood.

Related: Earth’s inner core may be slowing down compared to the rest of the planet

Now, scientists studying seismic waves created by large earthquakes have recorded waves bouncing back and forth like a ping-pong ball along Earth’s diameter five times — the highest reflection rate ever recorded, smashing the previous record of two times. Observing how these waves, which are generated when Earth’s tectonic plates move suddenly during earthquakes, get distorted as they go through Earth’s center is helping scientists bring the elusive innermost core into clearer focus.

The team behind the latest research probed Earth’s center in an innovative way using three earthquake datasets, each of which saw the core differently, study co-author Hrvoje Tkalčić told Space.com in an email. One of the events they studied was the 7.9-magnitude earthquake that occurred in 2017 in the Solomon Islands (opens in new tab).

“Earth oscillates like a bell after a large earthquake, and not just for hours, but days,” Hrvoje Tkalčić, a geophysicist at the Australian National University and co-author of the latest study, said in a statement (opens in new tab).

To study the innermost core well, scientists need seismometers located at the very opposite ends of earthquakes — points they call antipodes — which are often in oceans. So they have very little data to work with, thanks to the high cost associated with installing seismic stations in such remote areas.

“The innermost inner core is notoriously difficult to probe by seismic waves,” Tkalčić told Space.com in an email.

Related: How has Earth’s core stayed as hot as the sun’s surface for billions of years?

So the team combined seismic data recorded by different data centers worldwide about the large earthquake in the Solomon Islands, and studied a type of seismic wave called the primary, pressure or P wave. The P wave is the fastest of all seismic waves and the only one that passes through Earth’s center, so studying it as it crossed Earth’s center five times illuminated the planet’s deep interior.

Tkalčić’s team found that the wave took 20 minutes to travel the planet’s width. Each time it did so, they saw the innermost core’s “anisotropic” property on clear display: Seismic waves passing through the innermost inner core slowed in one direction while those moving through the outer layer slowed in a different direction.

“It simply means that the iron crystals — iron, which is dominant in the inner core — is probably organized in a different way than in the outer shell of the inner core,” Tkalčić said in the same statement (opens in new tab).

Scientists knew as early as 2003 (opens in new tab) that the innermost inner core is anisotropic (opens in new tab), so the latest research strengthens that knowledge with clearer evidence. In the new study, researchers found that the direction of P waves inside the innermost core is slowest at an “oblique” angle with the equatorial plane, or 50 degrees from Earth’s rotation axis.

“This is critical, and this is why we can say we’ve detected ‘distinct’ anisotropy in the innermost inner core,” the authors wrote in a piece published by The Conversation (opens in new tab).

There is strong evidence that slow-moving iron in Earth’s core powers the planet’s geodynamo, which leads to generation of the Earth’s global magnetic field. So understanding what’s happening at the planet’s very center will shed light on how the magnetic field behaves and at times reverses.

Although the latest study adds to the growing body of evidence that confirms the innermost core to be Earth’s fifth layer, it may be a while before textbooks are updated, Tkalčić told Space.com.

“After all, when the inner core was first hypothesized in 1936,” Tkalčić said, “it took some time for [the] model of the Earth to settle in and the textbooks to be changed.”

Soon after Earth’s innermost inner core makes its way to textbooks, food analogies will follow. Perhaps a dark chocolate center inside the chocolate chip?

The research is described in a paper (opens in new tab) published online Feb. 21 in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @Sharmilakg (opens in new tab). Follow us @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab), or on Facebook (opens in new tab) and Instagram (opens in new tab).