Astronomers have discovered a giant alien planet that is shaping the spiral arms developing in gas and dust around its parent star.

The planet also happens to be the reddest planet outside the solar system, or ‘exoplanet,’ ever seen, scientists have said.

Spiral arms are structures usually associated with galaxies, with images of our spiral galaxy, the Milky Way, providing a striking example of such a structure. Spiral arms aren’t limited to galaxies; gas and dust around young stars can also develop these features too.

Related: The strangest alien planets we’ve seen so far

Located around 500 light-years from Earth, the star, MWC 758, is estimated to be just a few million years old, practically an infant in comparison to our ‘middle-aged’ sun, which is around 4.6 billion years old.

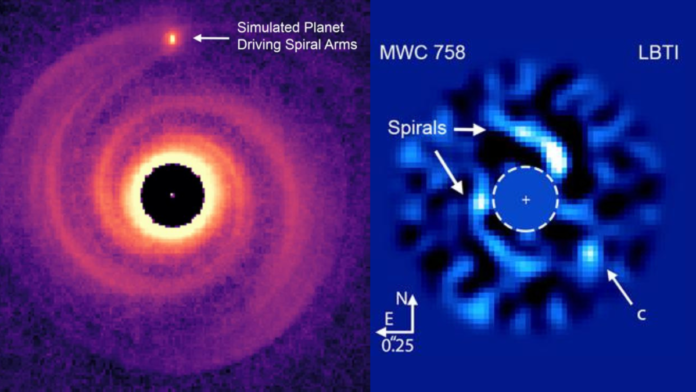

And just as the sun was in its infancy, MWC 758 is surrounded by a disk of planet-birthing material called a protoplanetary disk. But since at least 2013, astronomers have been aware of a spiral pattern forming two arms in this protoplanetary disk. University of Arizona researchers now think that those twin spiral arms are the work of a massive planet, dubbed MWC 758c, which orbits the star at a distance equivalent to 100 times the distance between Earth and the sun.

“Our study puts forward a solid piece of evidence that these spiral arms are caused by giant planets,” research lead author and University of Arizona Steward Observatory postdoc Kevin Wagner said in a statement. “And with the new James Webb Space Telescope, we will be able to further test and support this idea by searching for more planets like MWC 758c.”

Related: Hubble telescope spies ‘peek-a-boo’ exoplanets amid star’s dust rings

Protoplanetary disks like this one and the one that once formed the solar system usually take around 10 million years to dissipate. The debris comprising them can either be ejected from the system, can be swallowed by the infant star, or can be used as the building blocks for planets, moons, asteroids, and comets.

“I think of this system as an analogy for how our own solar system would have appeared less than 1% into its lifetime,” Wagner said. “Jupiter, being a giant planet, also likely interacted with and gravitationally sculpted our own disk billions of years ago, which eventually led to the formation of Earth.”

Spiral arms in protoplanetary disks are fairly common. Of 30 disks identified in relatively nearby young star systems, astronomers have found around 10 have their own spiral arms.

“Spiral arms can provide feedback on the planet formation process itself,” Wagner said. “Our observation of this new planet further supports the idea that giant planets form early on, accreting mass from their birth environment, and then gravitationally alter the subsequent environment for other, smaller planets to form.”

The leading theory is that these spiral arms are sculpted when a massive gas giant pulls on material swirling around its parent star. Until now, however, astronomers have failed to spot the planets that could be acting as cosmic sculptors for these arms.

“It was an open question as to why we hadn’t seen any of these planets yet,” Wagner said. “Most models of planet formation suggest that giant planets should be very bright shortly after their formation, and such planets should have already been detected.”

How a spiral arms dealer remained hidden

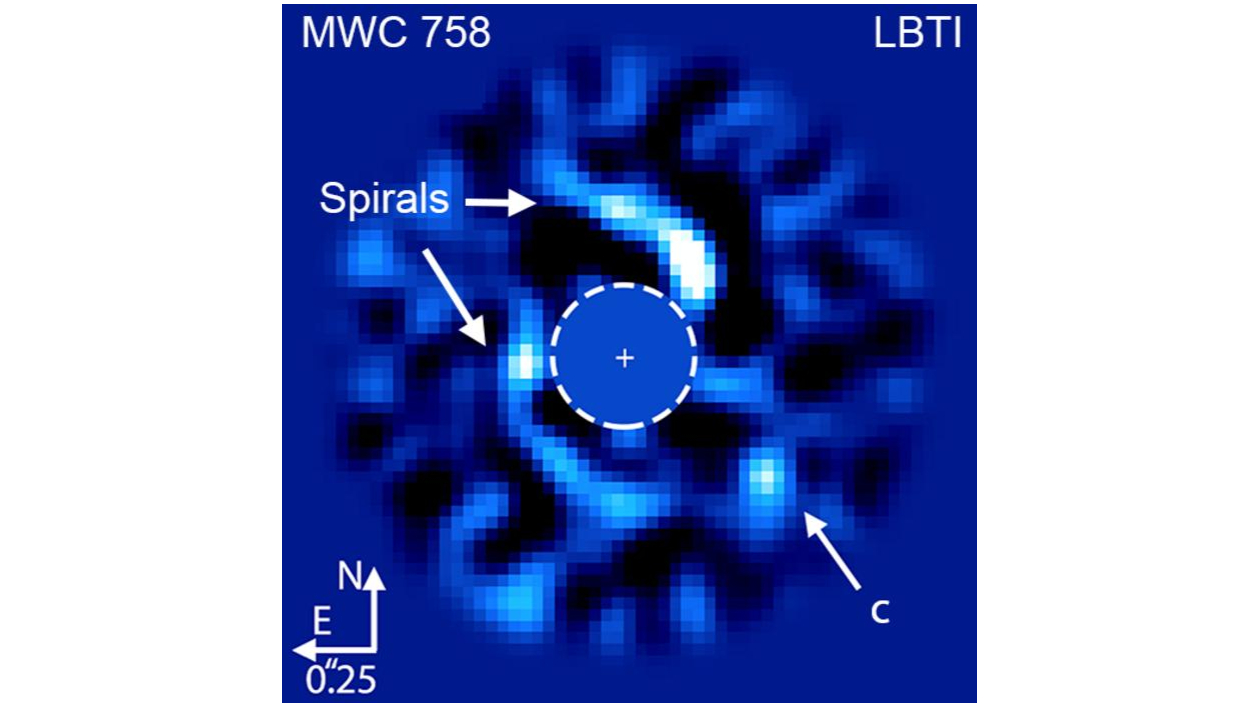

The University of Arizona spotted the spiral arms dealer around MWC 758 using the Large Binocular Telescope Interferometer (LBTI). While most exoplanet-hunting telescopes search for planets outside the solar system using short wavelengths at the blue end of the electromagnetic spectrum wavelengths, this University of Arizona-built instrument can observe the universe at longer wavelengths in the mid-infrared range.

This means that while MWC 758c evaded other telescopes with its unusual and unexpected red-hue, it couldn’t give the LBTI the slip. LBTI lead instrument scientist Steve Ertel explained that longer, redder wavelengths are more difficult to detect than shorter bluer wavelengths because of the thermal glow of Earth’s atmosphere and that of the telescope itself.

As one of the most sensitive infrared telescopes ever constructed, the LBTI can even outperform the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which also sees the cosmos in infrared when it comes to detecting planets hidden around their stars. The team also has ideas about why the planet may have been able to stay hidden for so long.

“We propose two different models for why this planet is brighter at longer wavelengths,” Ertel said. “Either this is a planet with a colder temperature than expected, or it is a planet that’s still hot from its formation, and it happens to be enshrouded by dust.”

If MWC 758c is enshrouded by a large amount of dust, this material would be absorbing short-wavelength light resulting in the planet appearing bright only at longer red wavelengths.

If the exoplanet is surrounded by a great deal of dust, this may indicate that it is still forming or even that it is in the process of gathering its own moons as the solar system gas giant Jupiter did billions of years ago.

“In the other scenario of a colder planet surrounded by less dust, the planet is fainter and emits more of its light at longer wavelengths,” research co-author and University of Arizona theoretical astrophysicist Kaitlin Kratter said.

If this chillier model for MWC 758c is correct, this means that there may be something happening in young planetary systems such as this that results in planets being colder than expected when they form. This might have an impact on planet formation models and on the techniques that astronomers currently use to hunt exoplanets.

“In either case, we now know that we need to start looking for redder protoplanets in these systems that have spiral arms,” Wagner said.

The researchers behind the detection of MWC 758c will now view the exoplanet with the JWST in 2024 in an effort to distinguish between potential scenarios at work in this infant planetary system.

“Depending on the results that come from the JWST observations, we can begin to apply this newfound knowledge to other stellar systems,” Wagner said, “and that will allow us to make predictions about where other hidden planets might be lurking and will give us an idea as to what properties we should be looking for in order to detect them.”

The team’s research is published in the journal Nature Astronomy.