The European Space Agency (ESA) mission Aeolus came to a fiery end when it burned up in Earth’s atmosphere. Even in death, the trailblazing spacecraft broke new ground. Aeolus was brought back to Earth as part of a first-of-its-kind guided, safe reentry operation that will help inform future reentry missions.

U.S. Space Command said that the ESA craft entered Earth’s atmosphere at around 3 p.m. EDT on Friday (July 28) above Antarctica. The maneuvers ensured that any pieces of Aeolus that didn’t burn up in the atmosphere fell harmlessly into the ocean. Speaking at a press conference held on Wednesday (July 19), the head of ESA’s Space Debris Office Holger Krag explained that just 20% of the Aeolus satellite was expected to survive reentry, adding there are no plans to recover any of these pieces.

During the briefing, Krag also explained how unique this reentry operation was: “This is quite unique, what we’re doing. You don’t find really examples of this in the history of spaceflight. This is the first time to our knowledge, we have done an assisted re-entry like this.”

Related: European satellite falls to Earth in landmark ‘assisted reentry’

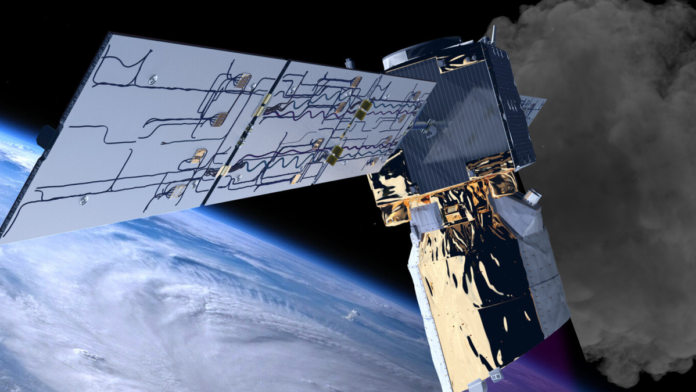

Aeolus, named after the ‘keeper of the winds’ in Greek mythology, was launched to orbit on Aug. 22, 2018, on a Vega rocket from Europe’s spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana. As its name implies, the primary mission of Aeolus was to become the first instrument to measure Earth’s winds from space.

Not only did Aeolus contribute to climate research, but the satellite also provided data that was essential for weather forecasting, especially during COVID lockdowns when weather instruments carried by aircraft were grounded.

Orbiting the planet for five years, the 3,000-pound (1,360-kilogram) spacecraft well outlived its originally planned mission lifetime of just 36 months. It eventually almost completely exhausted its fuel supply and it was shut down by operators in early July 2023. Following this, the spacecraft began falling to Earth with increasing speed.

ESA scientists decided that what little remained of Aeolus’ fuel would be used to perform reentry maneuvers that would bring it safely back down to Earth. While modern satellites are built with such operations in mind, in the 1990s, when Aeolus was being planned, there were no requirements to do this.

That meant that performing such an operation with a craft never designed with maneuvers in mind required a great deal of preparation by ESA scientists.

Reentry maneuvers began on Monday (July 24), when the spacecraft had fallen from its operational sun-synchronous orbit 200 miles (320 kilometers) above Earth to an altitude of around 174 miles (280 kilometers). The spacecraft fired its thruster twice, with this burn lasting around 38 minutes. This brought the altitude of the satellite down to around 155 miles (250 km) over Earth.

On Thursday (July 27), Aeolus fired its thrusters a further four times, lowering its orbit further to around 93 miles (150 km) altitude. On Friday, the craft received its final-ever command from ground control that resulted in it entering the atmosphere around fives hours later where it began to burn up.

The knowledge gained from these operations will be used in the future to de-orbit other spacecraft and satellites safely. Krag pointed out that this is something vitally important, with around 10,000 spacecraft currently orbiting Earth, 2,000 of which are “dead.” And though there are no incidents of man-made objects falling from space and injuring people or causing major property damage, with one large piece of space junk falling back to the planet on average every week, the possibility is one that the ESA takes very seriously.

“The teams have achieved something remarkable. These maneuvers were complex, and Aeolus was not designed to perform them, and there was always a possibility that this first attempt at an assisted reentry might not work,” ESA’s Director of Operations, Rolf Densing, said in a statement. “The Aeolus reentry was always going to be very low risk, but we wanted to push the boundaries and reduce the risk further, demonstrating our commitment to ESA’s Zero Debris approach.”

Densing is referring to the ESA’s Zero Debris Charter, which aims to make all ESA missions “debris neutral” by 2030. This will ensure that its space-based operations don’t just meet current standards but will meet future, more stringent regulations.

“We have learned a great deal from this success and can potentially apply the same approach for some other satellites at the end of their lives, launched before the current disposal measures were in place,” Densing concluded.