The stars have not been aligned for Europe’s first Martian rover ExoMars, but scientists still think the aging vehicle can play a big role in answering one of the biggest questions in Mars exploration: has there ever been life on the Red Planet?

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Rover is probably the most high-profile space industry casualty of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Originally expected to launch in 2018, the rover was finally declared ready to go (after several delays) for a launch in September this year atop Russia’s Proton rocket from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine put a stop to these plans.

ESA officially terminated cooperation on the ExoMars mission with Russia in July, leaving the rover, conceived in 2004, once again in limbo, and more importantly, without a landing platform to place it on the surface of Mars. (That landing platform was built by Russia, who joined the ExoMars program in 2012 following the withdrawal of the original partner, NASA, in 2012.)

ESA has yet to decide on the mission’s fate. Having spent $1.3 billion on the program already, it will have to choose between scrapping the rover altogether or forking out another substantial sum to replace the Russian bits.

Related: A brief history of Mars missions

In the case of the latter option, the most optimistic estimates see the ExoMars rover leaving Earth in 2028. For many European scientists, scrapping the mission should not be an option at all, and not just because of the investment. Even though NASA’s Perseverance has been smashing its sample collection targets, and plans for a mission that would bring those samples to Earth are already underway, there is a lot the aging ExoMars rover can contribute to our understanding of Mars, they say. And some of those questions, in fact, cannot be answered by the stellar Perseverance.

“[The rover’s instruments] are going to get a bit old,” John Bridges, a professor of planetary science at Leicester University in the U.K., told Space.com. “But as long as the maintenance can be done, it doesn’t actually bother me too much that we’re not using the most cutting-edge technology. Even if we’re going by bicycle rather than by the newest car, it doesn’t really matter, as long as we get there.”

The promise of the drill

The biggest strength, and scientific promise, of the Rosalind Franklin ExoMars rover is its 6.6-foot (2 meters) drill, which, according to some astrobiologists, may have a higher chance of finding traces of past or present Martian life on Mars than the agile Perseverance.

“The rock pieces that Perseverance collects are from the immediate surface [of Mars],” Susanne Schwenzer, an astrobiologist at Open University in the U.K., who is also an interdisciplinary scientist on the ExoMars mission and a member of the science teams of NASA’s Curiosity and the Mars Sample Return missions, told Space.com. “And this immediate surface is bombarded by galactic cosmic rays, and the UV rays [from the sun], which destroy organic materials.”

Unlike Earth, Mars has no protective magnetic field and a very thin atmosphere, so there is nothing to filter this sterilizing radiation, some of which can penetrate several meters deep into the Martian rocks.

“[The effects of the radiation] diminish exponentially, so the first centimeters [inches] are the worst hit,” Schwenzer said.

That doesn’t mean that Perseverance cannot find traces of life, just that detecting the organic molecules in the burnt surface layers might require a more challenging scientific analysis, Schwenzer added.

“The advantage of the return samples is that we will have them in our labs over here,” Schwenzer said. “If we find something that we can’t answer with the instruments that we have, we can wait for the right technology to be developed. It took until the late 1990s to find water in the Apollo samples because they didn’t have the right instrumentation at that time.”

The deep excavations that the ExoMars rover was built for can, in fact, help scientists understand Perseverance’s rocks and the alteration they underwent due to the bombardment by radiation.

“[The ExoMars rover] will help us understand how the organics degrade with depth or do not degrade and are preserved at deeper layers,” Schwenzer said.

Europe’s wrong turn

Bridges agrees with Schwenzer. But there are other reasons why continuing with ExoMars should be the only option on the table, he thinks. A generation of European scientists has tied their careers with the mission, which may have always been a bit of a moonshot for Europe, ever since its inception in 2004.

“When we started ExoMars in 2004, it was way off the capabilities [of ESA and the European space industry] to do it,” Bridges said. “So we got the Americans in to land it and when the Americans pulled out, ESA just looked around, and the Russians put up their hand, and it was done.”

Bridges describes the partnership with Russia, hastily put together by ESA leadership under General Director Jean-Jacques Dordain in 2012, as “a strategic mistake.”

“I think we should have hit the pause button back then and have a harder discussion across the European communities about what we were going to do,” he said.

At that time, the onset of the conflict in Ukraine was still two years away, but Russia was already guilty of stirring a bloody war in Georgia (opens in new tab); its actions in the Caucasian country were overwhelmingly overlooked by the international community at that time.

“There’s frustration and disappointment, because so much work has gone into ExoMars,” Bridges said. “The instruments, the science teams. But we should probably still stick with it and try and recoup all that scientific investment, not just throw up our hands in disappointment and walk away from it.”

The call to confirm life on Mars

Schwenzer adds that to provide the ultimate answer to the big question, whether there has ever been life on Mars, scientists would want to review as much data as possible.

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” Schwenzer said, quoting famous astrobiologist Carl Sagan. “We can’t just find one molecule that is usually produced by life on Earth and claim that we have found life on Mars. We can’t make that claim unless we can absolutely exclude that anything else could have made that molecule. And in order to do that, we would need all the information that we can get, not just that from one mission.”

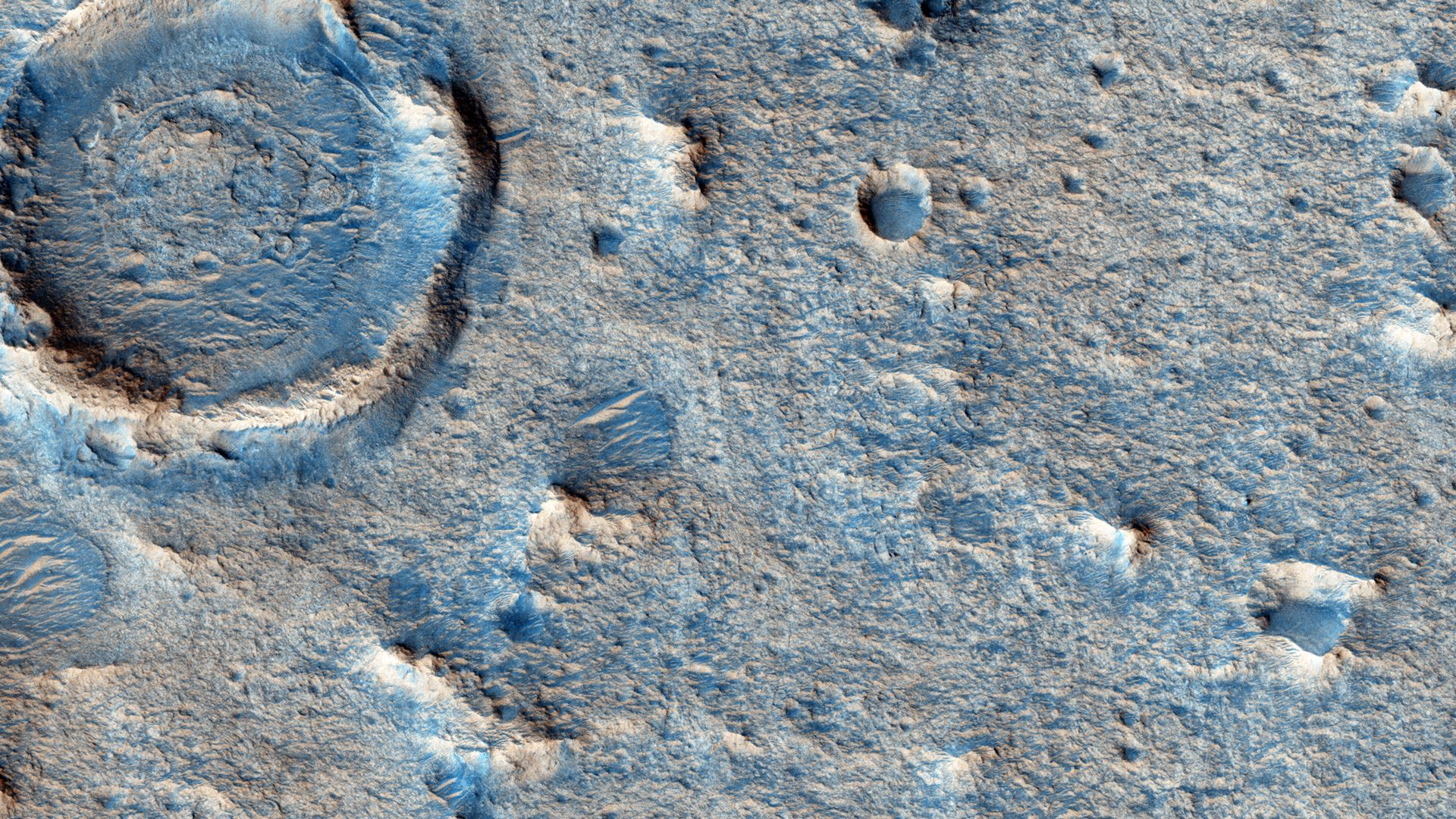

ExoMars’ projected landing site in Oxia Planum, an ancient clay-rich basin near Mars’ northern tropic, was carefully selected by a pan-European scientific consortium as it offers the best conditions to harbor traces of life.

Formed about 4 billion years ago, the basin, covered with fine-grained sediments, has a catchment area of thousands of miles, Bridges said, where water in the past used to accumulate.

“It’s a very different area to Jezero Crater [where Perseverance roams],” Bridges said. “But because we have seen one, that doesn’t mean that it is not worth going to see the other. We have still only explored a tiny fraction of the Martian surface and we shouldn’t fall into the trap of assuming that we’ve seen that, done that.”

Falling behind

The ExoMars conundrum, Bridges suggests, highlights weaknesses in ESA’s strategy, and undermines the agency’s aspiration to be the world-class player it desires to be.

ESA, a partnership of 22 European member states, was beaten to the surface of Mars by China, which only revealed its plans for the Zhurong rover in 2014. Chinese landers, including the famous Yutu rover, have dominated moon exploration in the past decade. Japan’s space agency JAXA, in the meantime, has built a legacy of returning samples from asteroids.

“ESA has this problem that they can be left flapping in the breeze a bit,” Bridges said. “If external factors change, they don’t seem to quite have the size or strength to withstand being buffeted about. Part of that is because they haven’t really decided what their strategy is, what they really want to be doing, compared to JAXA or China’s National Space Administration, who know exactly what they want to do and they just get on and do it.”

ESA is currently evaluating options for the ExoMars rover, which it will present to its member states later this year. Among the possibilities is a return to the original partner NASA, who could land the rover using its proven technologies, Bridges said, but with a substantial financial contribution from ESA.

NASA’s recent decision to scrap the European Mars sample return fetch rover and replace it with NASA-built helicopters, may provide an impetus to stick with the troubled ExoMars.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.