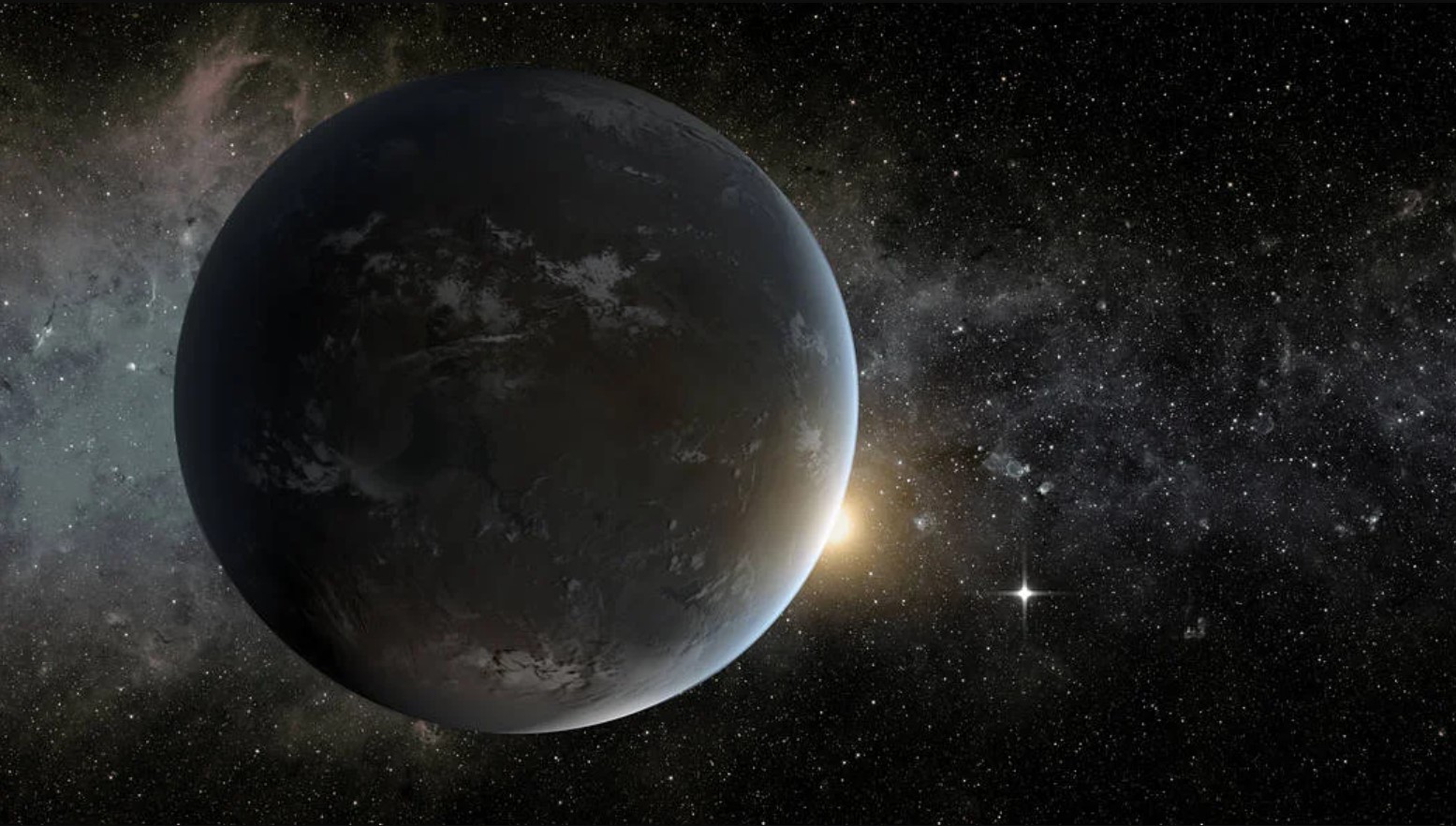

What would happen if we had an additional planet in our solar system? Not in the fringes like the hypothetical Planet Nine way beyond Pluto, but smack in the middle of Mars and Jupiter?

Such a world would wreak havoc on the orbits of most planets, according to new research that simulated a super-Earth — a term used for worlds that are more massive than Earth but lighter than gas giants — and recorded the fate of all eight planets. Results show that tiniest changes in the orbit of Jupiter, which is more massive than all other planets combined, has a profound and devastating effect on the delicately balanced orbits of other planets.

“It all works like intricate clock gears,” Stephen Kane, an astronomer at the University of California in Riverside and the study’s sole author, said in a statement (opens in new tab). “Throw more gears into the mix and it all breaks.”

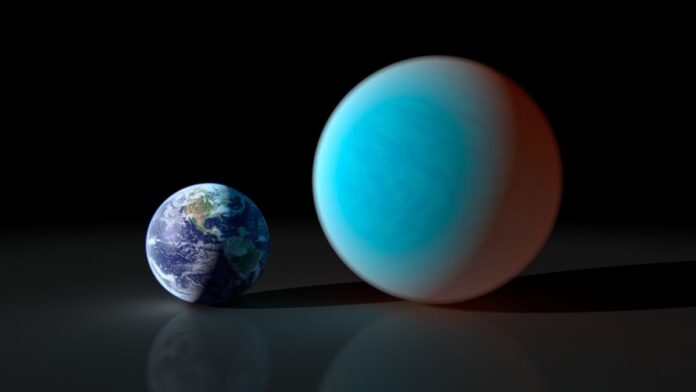

Related: Super-Earths: Exoplanets Close to Earth’s Size

Our solar system was long considered a template for all planetary systems. In the last 25 years, however, it has quickly and firmly become an outlier for lacking its own super-Earth.

NASA’s exoplanet hunting missions such as Kepler and Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) have helped astronomers realize that such planets are surprisingly very common in the Milky Way: A third of all exoplanets are super-Earths. They think our solar system does not have a super-Earth because Jupiter suppressed its formation when it migrated significantly toward the asteroid belt and back out again, during which it sent a lot of material onto the sun. So they have a hard time understanding such worlds that are common in other solar systems, thanks to a lack of local data that would otherwise help them model compositions and other properties.

This “has been a source of frequent frustration” among the exoplanet community, Kane told Space.com in an email. “My study was therefore intended to answer the question: What if your wish came true?”

Inner four planets are especially vulnerable

Super-Earths can be anywhere between two to 10 times as massive as our planet, so Kane simulated planets of various masses and placed them at multiple distances in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. He started with a super-Earth at twice the distance between Earth and the sun or 2 astronomical units (AU; 185 million miles or 297 million km) and increased the distance all the way to the outer edge of the asteroid belt, at 4 AU (371 million miles or 597 million km). This led to thousands of simulations, each of which began at the present time and ended 10 million years later. Every 100 years, Kane recorded the consequences to each of the eight planets in the solar system.

These outcomes showed that all four inner planets — Mercury, Venus, Mars and Earth — are particularly vulnerable to orbit changes; some or all four planets got kicked out of the solar system in many cases. None of the thousands of simulations showed Jupiter or Saturn leaving. But in a few cases, the two gas giants did toss out other planets, including the newly added super-Earth itself as well as Uranus, causing chaos among its moons.

“I wouldn’t hold out too much hope for the moons remaining in stable orbits around the planet as it is sent hurtling out of the solar system,” Kane said.

When a planet seven times Earth’s mass like Gliese 163c was placed a little beyond Mars, the simulation showed that the orbits of all four inner planets became unstable. Earth’s and Venus’ orbits became eccentric or egg-shaped enough that they had “catastrophic close encounters.” The change in their orbits then released energy that was transferred to Mercury, and it got kicked out soon after. Mars survived only until halftime, and Earth and Venus made their way out around eight million years.

Gas giants can hold their own

Unlike terrestrial planets, gas giants, especially Jupiter and Saturn, were less severely affected by the additional planet. Their orbits were slightly unsteady only at mean-motion resonance (MMR) locations — specific spots where two planets have orbital periods that are a simple integer ratio of each other. (For example, an object in a 3:1 MMR with Jupiter orbits the sun exactly three times for every one orbit of Jupiter.)

So when Kane placed the same Gliese 163c-like super-Earth in the outer reaches of the asteroid belt at 3.8 AU, it ended up being in a 8:5 MMR with Jupiter and a 4:1 MMR with Saturn. As a result, the orbits of both gas giants become more egg-shaped, so much so that they removed the super-Earth first and Uranus later. Kane’s study found that in this case, even the slightest of changes in the outer solar system heavily influenced the inner planets; Mars was thrown out a couple million years after Uranus, for example.

“What surprised me the most in the study was the sensitivity of the overall solar system architecture to the resonances of Jupiter,” Kane told Space.com in an email.

The addition of a super-Earth is least chaotic if the planet is placed towards the end of the asteroid belt near 3 AU (278 million miles or 447 million km), according to the study. Here, it would interact minimally with giant planets and cause little disruptions to the solar system, Kane argues.

In this case, “one major lacuna that needs to be further explored is the stability of the solar system on longer timescales (say, 1 billion years),” Manasvi Lingam, an astronomer at the Florida Institute of Technology who was not involved in the study, told Space.com in an email.

Overall, the study shows “how important Jupiter is for the dynamics of the solar system,” Kane told Space.com, “and that even relatively small changes can make an enormous difference in the stability of our system.”

Super-Earths may be common in most solar systems because giant planets like Jupiter are a rare occurrence: Only ten percent of sun-like stars host giant planets at distances from the sun like ours, and the number drops further for older stars.

Kane said researchers have often speculated whether our solar system could safely harbor an additional planet between Mars and Jupiter, and the answer seems to be a resounding no.

“If you are an exoplanet person and find a genie in a bottle, please don’t wish that the solar system had a super-Earth,” Kane tweeted (opens in new tab). “You might accidentally destabilize the solar system!”

The research is described in a paper (opens in new tab) published Feb. 28 in The Planetary Science Journal.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @Sharmilakg (opens in new tab). Follow us @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab), or on Facebook (opens in new tab) and Instagram (opens in new tab).