There are many in Mars exploration circles that see Valles Marineris as a “tell all” place, ripe for human exploration that can uncover the planet’s history and its capacity to sustain microbial life.

That said, how best to investigate the multifaceted geology in evidence at this site? Can future crews on the Red Planet dive safely into this huge canyon system? And what awaits those probing a vast region that’s been branded as the Grand Canyon of Mars?

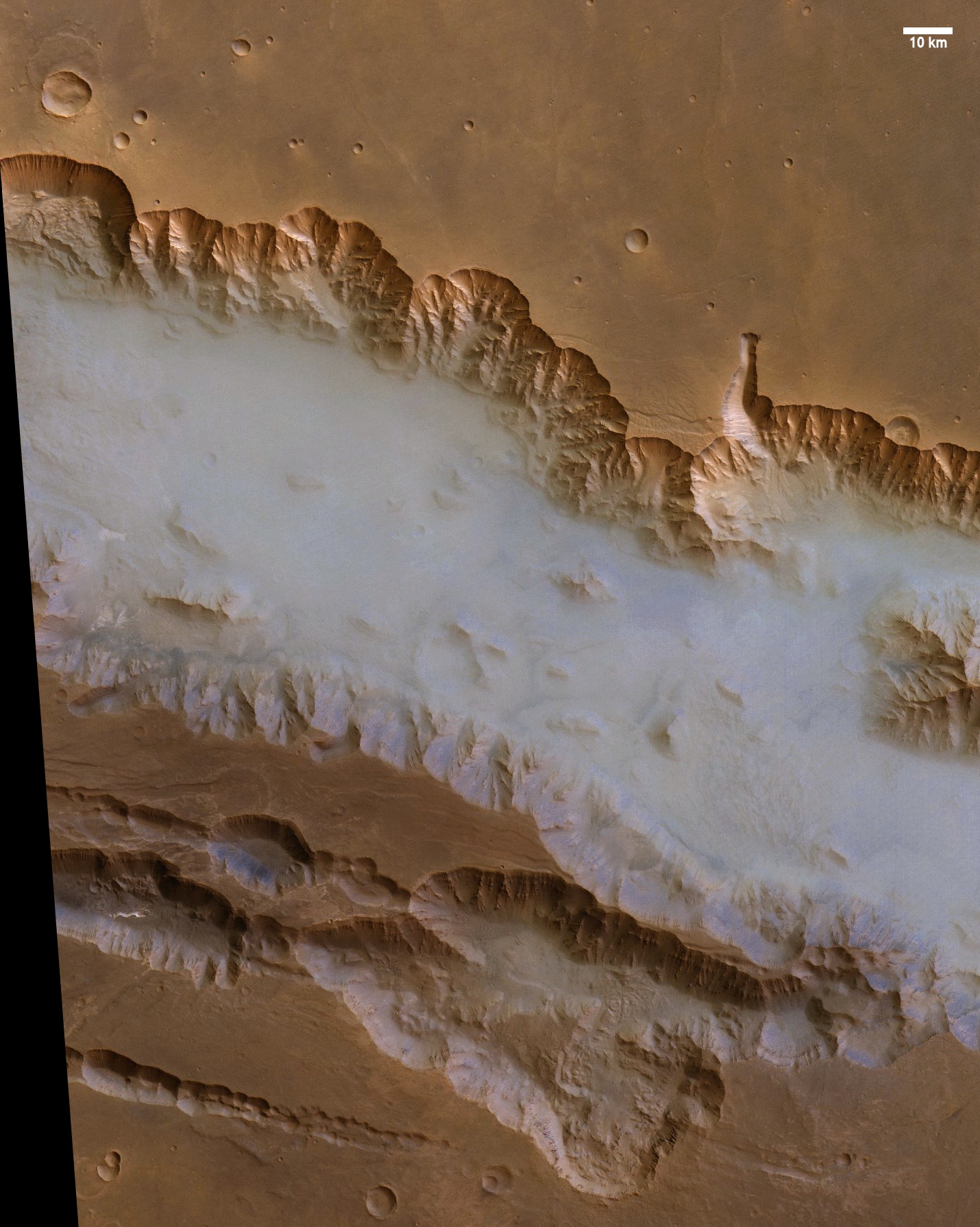

Valles Marineris is a humongous feature; a system of canyons cutting across the Martian surface spanning 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers), covering about one-fifth the circumference of Mars. At some points, this colossal chasm is 125 miles (200 km) wide. In certain places, the canyon floor reaches a depth of 5 miles (8 km).

Bottom line: that’s far deeper than Earth’s Grand Canyon.

Related: Glaciers on Mars likely helped carve Red Planet’s ‘Grand Canyon’

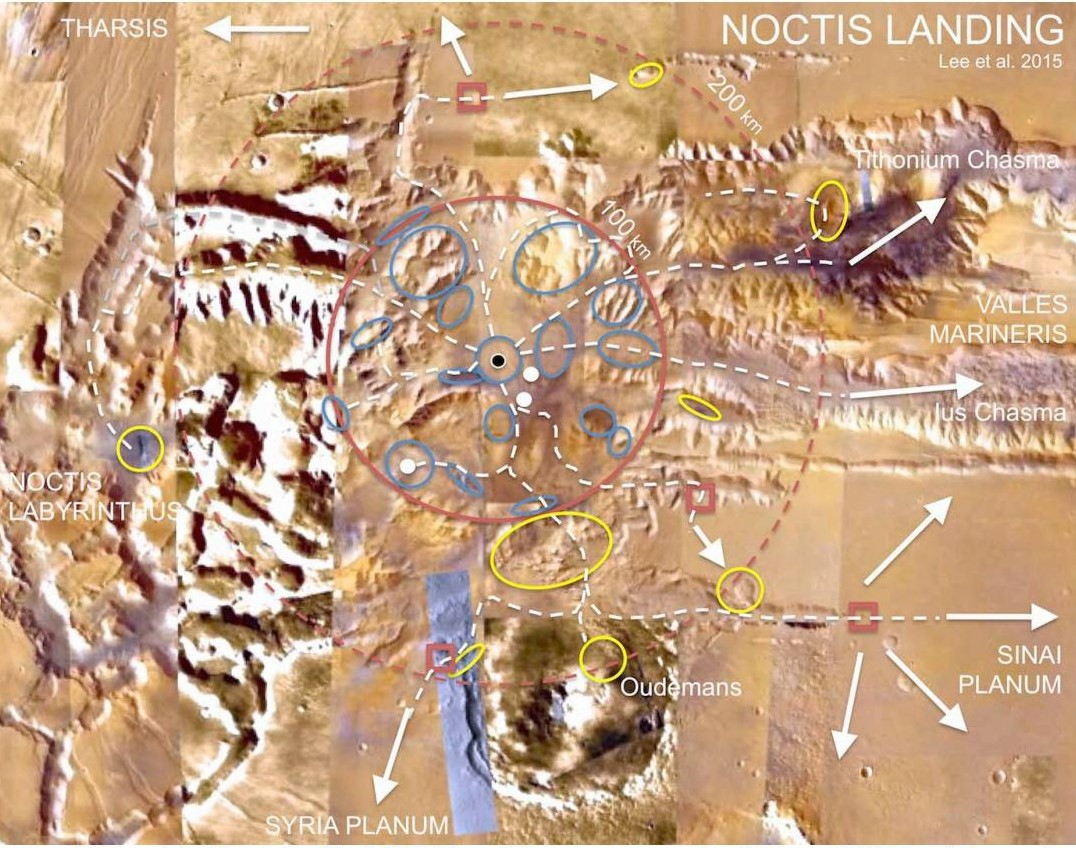

To encourage on-the-spot human studies of Valles Marineris, some scientists have pinpointed and provisionally named an area known as the “Noctic Landing” site. Its strategic location allows the shortest possible surface excursions to the Martian volcanic plateau of Tharsis as well as Valles Marineris — that grand feature and region on the Red Planet that exposes the longest record of Mars’ geology and evolution through time.

Tharsis is the area of Mars that has experienced the longest and most extensive volcanic history, and might still be volcanically active. Some of the youngest lava flows on Mars have been identified on the western flanks of the Tharsis Bulge.

Furthermore, those flows are within driving range of future pressurized rover traverses.

Top priority science

“I think that, when it comes to planning human missions to Mars, we might be past the point of thinking only about notional science objectives in location-agnostic ways,” said Pascal Lee, a planetary scientist at NASA Ames Research Center in California and the SETI Institute.

Lee is chairman of the Mars Institute, an international, non-governmental, non-profit research organization dedicated to advancing the scientific study, exploration, and public understanding of Mars. He’s also director of the NASA Haughton-Mars Project, an international multidisciplinary field research project focused on Mars analog studies at the Haughton impact crater site on Devon Island in the High Arctic.

We can and should, right now, look for human landing sites where most if not all our top priority science objectives could be met, Lee told Space.com. That human touchdown zone would likely offer multiple ways of extracting water locally — something a robotic scouting mission could ascertain — and where it would make sense to establish a base for long term exploration, he said.

At the crossroads

Lee is passionate that such a site that he dubs Noctis Landing is an ostensibly flat transitional region between Noctis Labyrinthus (Latin for ‘the labyrinth of night’) and Valles Marineris proper.

Noctis Landing not only offers a large number and wide range of regions of interest for short-term exploration, it is also located strategically at the crossroads between Tharsis and Valles Marineris, which are key for long-term exploration. The area is distinguished for its maze-like system of deep, steep-walled valleys.

“If you head east or south from Noctis Landing, you go deeper into Valles Marineris and can look for signs of past life,” Lee said. “If you head west or north from Noctis, you climb onto Mars’ giant volcanoes with their many caves, and can look for extant life.”

No rock-climbing required

The upshot is that the Noctis Landing locale is unique, being at the literal junction of the search for signs of past and present life on Mars.

As for exploring Valles Marineris, the key advantage of Noctis Landing is that you can access all the rock layers of the canyon without having to resort to rock-climbing, Lee said.

“Thanks to the giant Oudemans impact crater nearby the Noctis Landing, giant slabs of Valles Marineris canyon walls have been laid flat there, ready for you to explore, one rock layer at a time, by just driving along the canyon floor,” Lee added.

Hidden water

Late last year, Igor Mitrofanov of the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow, Russia reported that a significant quantity of hidden water has been spotted at the central part of Mars’ dramatic canyon system, Valles Marineris.

The observation came via the European Space Agency-Roscosmos ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO). Mitrofanov is the principal investigator of the TGO-toted Fine Resolution Epithermal Neutron Detector (FREND) neutron telescope. That instrument is mapping the hydrogen — a measure of water content — in the uppermost meter of Mars’ soil.

Mitrofanov and colleagues found evidence for unusually high hydrogen abundances in the heart of Valles Marineris on Mars.

Unclear mix of conditions

“With TGO we can look down to one meter below this dusty layer and see what’s really going on below Mars’ surface — and, crucially, locate water-rich ‘oases’ that couldn’t be detected with previous instruments,” Mitrofanov stated (opens in new tab) in an ESA-issued statement.

“Assuming the hydrogen we see is bound into water molecules, as much as 40% of the near-surface material in this region appears to be water,” Mitrofanov said.

As the ESA statement puts it, the detection suggests that “some special, as-yet-unclear mix of conditions must be present in Valles Marineris to preserve the water — or that it is somehow being replenished.”

Mitrofanov and his research associates published their work (opens in new tab) in the March 2022 issue of the journal Icarus, stating: “Such ice not only is an intriguing material for searching frozen proto-life fragments or complex organic molecules from the early epoch of Mars, but also is an indispensable natural resource for future Mars exploration that is easy to exploit.”

Fog banks

NASA’s Lee underscored the intriguing finding that there’s frequent occurrence of fog in Valles Marineris. “While the average Martian atmosphere is generally considered to hold too little water vapor for it to be worth compressing and exploiting, the presence of ice fog, the most likely explanation for the fog banks frequently filling Valles Marineris, indicates that the Martian atmosphere could be locally supersaturated in water, possibly up to amounts worth extracting,” he said.

The presence of fog in Valles Marineris, Lee said, also suggests that at least part of the hydrogen detected by Mitrofanov and his associates is likely to be in the form of H2O, not just water of hydration in minerals.

Taking to the air

Purging Valles Marineris of its scientific holdings could be augmented by aerial vehicles, said Abigail Fraeman, a research scientist and Mars Science Laboratory Deputy project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

That view is clearly backed by the airborne success of NASA’s Ingenuity Mars helicopter at Jezero Crater.

“We can start to imagine all sorts of possibilities for future Mars exploration with aerial assets,” Fraeman told Space.com. “One of the benefits of exploring Mars from the air is the ability to travel much longer distances over terrains that would be too treacherous for rovers.”

Fraeman said that Valles Marineris is one example of a site that might really benefit from exploration by helicopters. “This platform could enable us to explore sections of really ancient crust exposed in the walls of the canyon, the steep layered sedimentary deposits in the canyon’s center, and even the mysterious recurring slope lineae which occur on steep slopes throughout Valles Marineris and might be formed by very salty liquid water.”

Exploring these features, Fraeman added, “would help us answer questions about the entirety of Mars’ history, from the first formation through the present day, and provide unprecedented insight into mechanisms that affect the climate and habitability of Mars, as well as rocky worlds beyond our solar system.”

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).