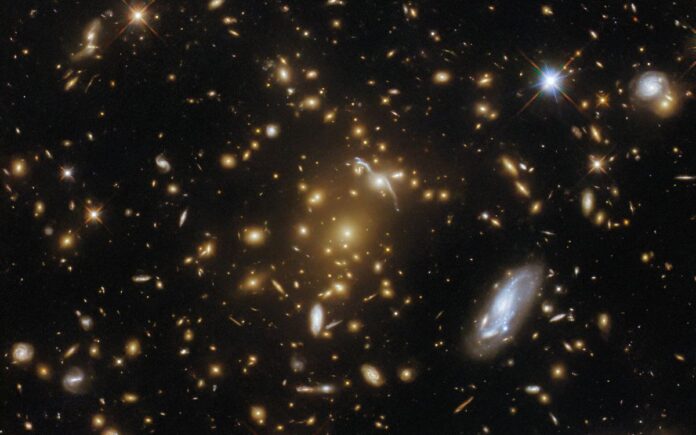

A new image from the Hubble Space Telescope gazes into the lair of a cosmic leviathan, a monstrous cluster of galaxies located nine billion light-years away in the constellation Draco.

Like a sea monster in ancient myth submerged and waiting to snatch unfortunate sailors to their doom, this celestial beast can be seen by the ripples around it. This leviathan is so titanic, however, that the ripples aren’t traveling the surface of an ocean or lake but rather are distortions in the fabric of space-time itself.

This particular galaxy cluster, known as eMACS J1823.1+7822, is one of five selected for observation by Hubble astronomers to determine the strength of this “warping” effect, which was first predicted by Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

Related: The best Hubble Space Telescope images of all time!

The 1915 theory, which is occasionally called Einstein’s geometric theory of gravity, predicts that, as bowling balls placed on a trampoline create a depression, objects with mass cause the very fabric of space-time to warp. This curvature gives rise to the force of gravity. And the greater the mass of a cosmic object, the more extreme the warping of space it causes.

Light travels across the universe in straight lines, but when it encounters a warp caused by a truly massive object, its path is curved. When the warping object is between Earth and a background object, it can curve light in such a way that the apparent position of the background object is shifted.

But when the intermediate or “lensing object” is truly massive — like a monstrous cluster of galaxies, for example — light from the background source takes a different amount of time to reach Earth depending on how close it passes to the natural cosmic lens.

This effect, called gravitational lensing, can make single objects appear at multiple points in the sky, often in stunning arrangements called Einstein rings and Einstein crosses. It can also cause background objects to appear amplified in the sky, a powerful effect that astronomers use to observe distant and early faint galaxies.

The distortion caused by massive clusters like eMACS J1823.1+7822 can also help astronomers study mysterious dark matter, which accounts for around 85% of the mass in the universe but is invisible because it does not interact with electromagnetic radiation. Because dark matter does interact gravitationally, however, the lensing of light by a galaxy or galactic cluster can help researchers map the distribution of dark matter.

In the new Hubble image, eMACS J1823.1+7822, made up of a collection of elliptical galaxies, acts as a gravitational lens. The cluster warps the shape of the galaxies around it, giving them a slightly elongated shape, turning some into arcs and others into bright streaks.

This particular image was created using Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys and its Wide Field Camera 3 instrument, both of which have the ability to view galaxies and stars in specific wavelengths of light. Observing objects at different wavelengths in this way allows for a more complete picture of the structure, researchers say.

In turn, such observations can reveal the composition and behavior of an object that would be hidden in visible light alone. When combined with the use of clusters like eMACS J1823.1+7822, gravitational lensing allows this to be done for some of the universe’s earliest galaxies. So powerful observatories like Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope can probe conditions found shortly after the Big Bang and the very birth of the universe.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).