OTTAWA, Canada — I found a portal to the moon behind an ordinary office door.

The lunar rover “Max” awaits in a huge facility painted in black, ready to explore a simulated moon landscape that sits beside the cubicle-filled offices of local company Mission Control. Surrounding the rover prototype is 4,000 square feet (370 square meters) of sand, providing a gigantic playground of landscape rocks, garden boulders and numerous “craters.”

Illuminating the scene is a single lamp high on the wall, casting a single harsh shadow. I turn away from the light and see my figure projected far into the distance; for a moment, I am transported to the iconic images and video of the 1960s and 1970s taken by the Apollo astronauts.

“The appearance is important; lighting is extremely critical,” said Adam Deslauriers, Mission Control’s space and education manager. He allowed that the “sun” is a bit dimmer than in real life, as the alternative would be “spending gazillions of dollars and having hazardous lamps.” But key aspects of the facility design included having a single and bright light source to provide one shadow, just like moon explorers see.

Related: See the moon Like the Apollo astronauts with these epic panoramic photos

Mission Control builds artificial intelligence systems to operate across the solar system for Earth observation, satellite servicing and other applications.

Already its software is en route to the moon on the United Arab Emirates’ Rashid rover, which is expected to land in April aboard a lander built and operated by Tokyo-based company ispace. Cameras aboard Max were tested for the Rashid mission, Deslauriers said, and Mission Control trained the models for machine learning in Ottawa as well.

Mission Control asked a fellow Canadian company to supply super-reliable rovers, to allow the Ottawa engineers to focus on their software specialty. Clearpath Robotics’ chair-sized “Husky” rovers (opens in new tab) fit the bill, Deslauriers said; the rover nicknames “Max” and “Ruby” come from a popular Canadian animated children’s show (opens in new tab) based on a book series by Rosemary Wells.

Because the rovers are so durable and can be designed for different driving experiences, other benefits likely accrue. For example, novice drivers like me (and dozens of children) have been allowed to drive these rovers as part of Mission Control’s mandate to do outreach. “When we did this lab, it was a conscious effort to get bulletproof, reliable rovers, and Clearpath has been awesome,” Deslauriers added.

Mission Control’s lunar focus is not accidental. NASA has numerous contracts under its Commercial Lunar Payload Services program for companies to send small rovers, landers and other payloads to the moon. That’s because the agency wants to bring private infrastructure to support the multinational NASA-led Artemis missions, which could land astronauts near the lunar south pole as soon as 2025.

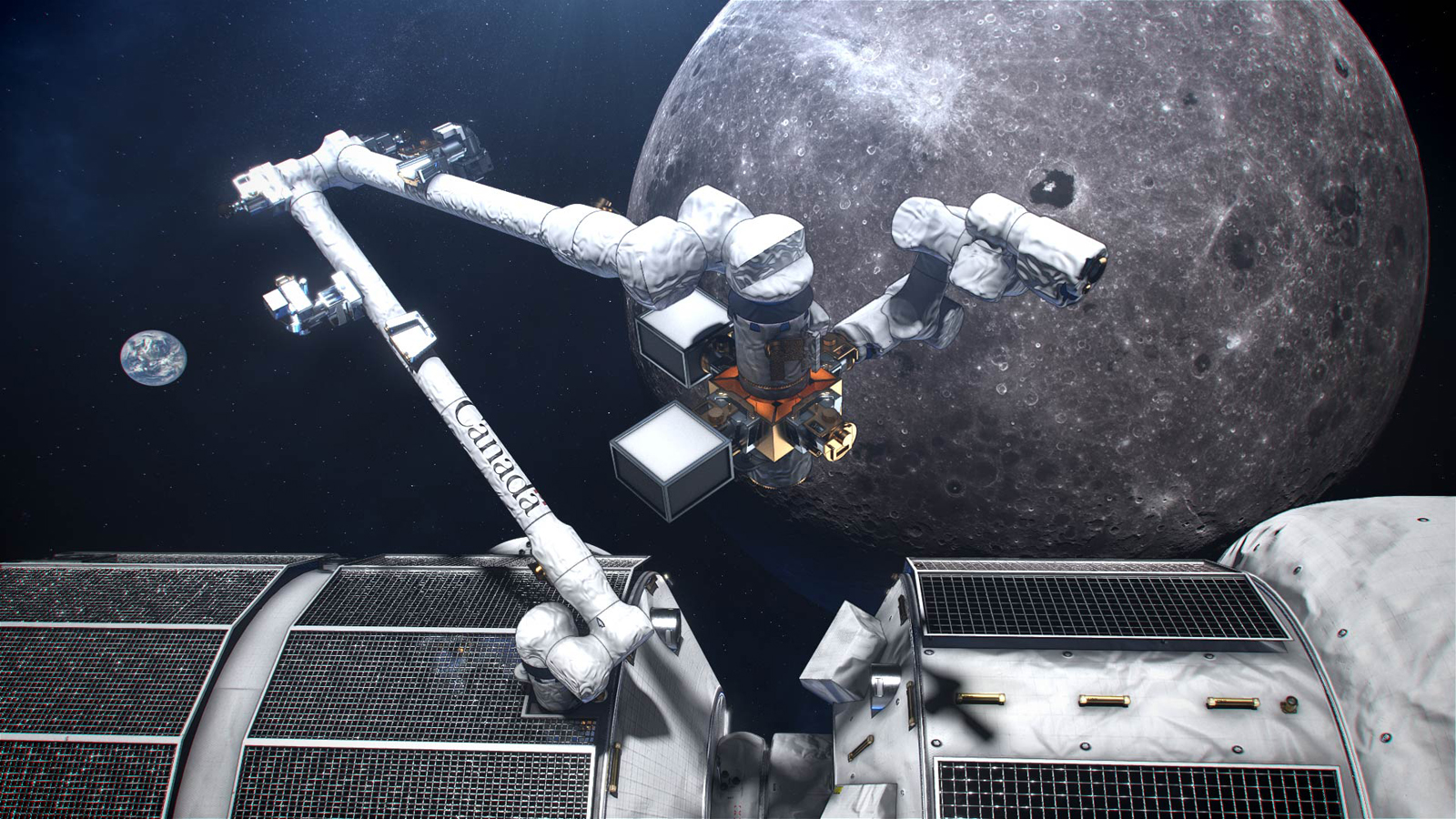

The Canadian Space Agency has its own projects, like the Lunar Exploration Accelerator Program (LEAP), to bring Canadian tech to the moon’s surface soon. This country is betting big on lunar exploration as well, working with the company MDA to develop a new robotic Canadarm3 to maintain NASA’s Gateway lunar space station.

This spring, Canada’s commitment will give the country a prestigious opportunity. One of Canada’s four active astronauts will take a seat aboard the moon-flyby Artemis 2 mission in 2024, alongside NASA colleagues and potentially, an astronaut from Japan as well.

(opens in new tab)

In a conference room, I eagerly take the wheel of Max. We turn on the “hazard” feature of the software, which brings a yellow and red sheen to obstacles otherwise difficult to see in the gray landscape. I carefully mouse over a semi-circle on the screen to get Max moving.

Moving the mouse forward, I creep the rover a few inches. A shift to the left or the right allows me to spin in slow “donuts.” Within moments, this space gamer finds herself gleefully exploring the landscape. With black-painted walls and sand under the wheels, the drive feels just like the real thing.

They made this course deliberately simple for me. There’s no two-second time delay for my movements, as there would be during the remote driving of an actual moon rover. Rocks are generously spaced out and thus easy to avoid. I quickly fall into zen, experiencing my own form of “slow TV” as Max drives in circles on my behalf (creating tracks that will need to be raked away later; I tell the rep assisting me to thank those employees after I leave.)

(opens in new tab)

Late that night, I think back to that moment when I stepped into Mission Control’s lunar portal for the first time. The scene filled me with a quietness I’ve only experienced a few times in my life: walking into the circle of Stonehenge, for example, or standing in the British Museum reading the signature of a birthday greeting (opens in new tab) likely penned by a Romano-British woman 2,000 years ago.

I’m not alone in this feeling during my simulated moonwalk, Deslauriers said. “It captures peoples imaginations. When we have visitors, it’s easier for them to remember us … ‘Mission Control, what one was that? Right, the one with the moon.’ Not just, ‘The guys with the computers and the desks.'”

I also will remember my lunar experience. I felt connections with the Apollo astronauts of the past, as well as those who will touch the moon in the future. We are all explorers of time, space and our communities. I can’t wait to see what wonders will be uncovered when we rake our gloved hands through lunar regolith once more.

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of “Why Am I Taller (opens in new tab)?” (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or Facebook (opens in new tab).