Just like the rest of us, NASA astronauts pay taxes.

Astronauts are supposed to file taxes no matter where they are working, even on the International Space Station (ISS). In 1970, in fact, one astronaut on a moon mission got in a pickle when he discovered he forgot to file his taxes before leaving Earth, which we’ll talk more about below.

Here we have very general guidance on how astronauts pay taxes and what happened to that astronaut in 1970, who was on a mission called Apollo 13. Remember that we are not tax experts here, so if you happen to be an astronaut (or potential astronaut) curious about how to pay taxes, please consult an accountant or similar tax professional familiar with your country.

Related: NASA gets $27.2 billion in White House’s 2024 budget request

Do NASA astronauts pay taxes?

Yes, NASA astronauts pay state and federal taxes as citizens of the United States in order to provide revenue for government spending. Depending on their situations, astronauts may also pay tax on property they own, investments or other revenue instruments, too.

“Federal government spending pays for everything from Social Security and Medicare to military equipment, highway maintenance, building construction, research, and education,” the U.S. Department of Treasury explains (opens in new tab).

U.S. civilian astronauts at NASA are paid on the federal government’s general schedule, between grades GS11 and GS14 depending on their experience, according to NASA (opens in new tab).

The general schedule (opens in new tab) for 2023 suggests a NASA astronaut’s base pay can range between $59,319 and $129,878. The pay scale, and taxes paid, will vary depending on where the astronaut is based and if they are working overseas (where they may receive per diems), among many other factors.

U.S. military astronauts assigned to NASA’s Johnson Space Center “will remain in an active duty status for pay, benefits, leave, and other similar military matters” and will therefore be paid according to their service, according to NASA (opens in new tab).

Related: Pioneering women in space: A gallery of astronaut firsts

How do NASA astronauts pay taxes from space?

NASA astronauts typically file taxes before they go to space, agency spokesperson Jay Bolden told Space.com in 2014. That is especially crucial given ISS missions typically last for at least six months at a time, and may be extended with short notice as missions or operations change.

Filing from space is not easy, or advisable. “While there are internet capabilities aboard the ISS, and it is ‘technically feasible’ it’s not especially practical,” Bolden told Space.com. “An action like that would require substantial forethought to preprogram laptop computer with tax software or have CD uploaded with tax software info.”

Even though the ISS has slightly faster internet today, the connections are prioritized for science experiments or manufacturing and presumably can be a little tricky, given space is a remote environment. There also may be security concerns in uploading secure information from the space station.

Astronauts may be able to file for extensions from space if their stay is unexpected or lengthened, for example (which happened during Apollo 13 in 1970, which you can read about below.) Astronaut Leroy Chiao asked his sister, an accountant, to file an extension on his behalf to the IRS in 2005, according to CNN (opens in new tab). He landed nine days after tax day and one of his first duties at home was to catch up on taxes.

“You do have to anticipate everything,” Chiao said of the family or civic responsibilities astronauts may face in space while being gone for months, including voting, birthdays, anniversaries or holiday celebrations.

Related: Holidays in space: an astronaut photo album

(opens in new tab)

How do international astronauts pay taxes?

Since NASA astronauts are bound by U.S. tax law, we can presume that international astronauts would also follow the laws of their own countries. Major ISS partners, for example, include Russia, the European Space Agency, Japan and Canada. Citizens of each country pay taxes to their respective national tax agency.

A select few astronauts have been dual citizens of the United States and Canada. Assuming the home agency is NASA and the astronaut is paid in the United States, they may file taxes to the IRS. But with Canadian citizenship involved, Canadian tax obligations are likely and there may be payments to the Canada Revenue Agency; do check carefully with a tax professional in these cases.

In the European Union, “the amount of tax each citizen pays is decided by their national government”, according to the union’s website (opens in new tab), and Japan and Russia have their own tax systems as well.

Related: The International Space Station: Inside and out (infographic)

(opens in new tab)

How do tourists and private astronauts pay tax from space?

Yes, space tourists and private, non-agency astronauts are also subject to taxes. A Canadian case study shows the importance of making sure you stay up to date with the tax authority in your home country.

In 2009, Canadian businessperson Guy Laliberté took a 12-day jaunt to the ISS to in part, film a documentary for the One Drop Foundation clear-water charity. Laliberté, who is founder of circus troupe Cirque du Soleil, paid the $41 million Canadian (roughly $41 million USD in 2009) trip through a Cirque corporation called Family Holdco. Laliberté then attempted to claim a shareholder benefit of $4 million Canadian in his tax return.

“Upon appeal, the Tax Court of Canada mainly disagreed with Laliberté’s contentions that the trip should be considered a promotional activity for Cirque du Soleil and One Drop Foundation, and should not be considered an activity giving rise to a shareholder benefit,” Canadian Lawyer Magazine stated (opens in new tab). Laliberté was said to owe back taxes due to this situation.

In the United States in 2021, U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Oregon) attempted to introduce legislation called the Securing Protections Against Carbon Emissions (SPACE) Tax Act to impose new excise taxes on space tourism trips, but that legislation did not get approved.

Related: Do space tourists really understand the risk they’re taking?

(opens in new tab)

The Apollo 13 tax issue

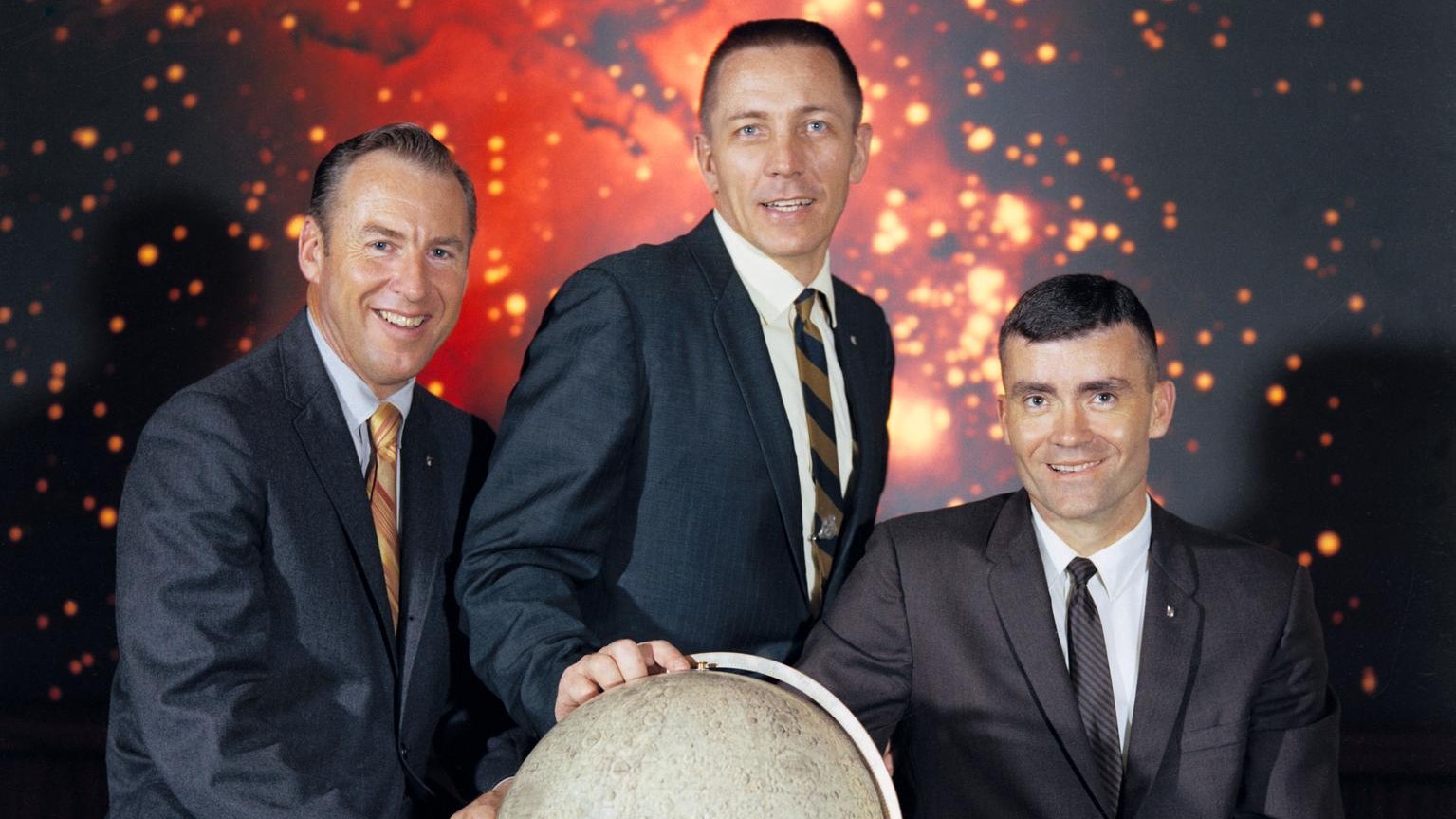

Apollo 13 astronaut Jack Swigert was assigned to the famous mission on April 8, 1970 just three days before the moon mission was launched on April 11. He was supposed to be on the backup crew, but the prime crew was unwittingly exposed to German measles. The prime crew member Swigert replaced — command module pilot Ken Mattingly — had no known immunity and was deemed a flight risk for the mission.

Swigert got occupied with last-minute preparations and found himself in space with no taxes filed, and no way to easily file them before the deadline. U.S. tax day was April 15, the same day his two crewmates (commander Jim Lovell and lunar module pilot Fred Haise) were supposed to be touching down on the moon. Splashdown on Earth wouldn’t be until April 21, according to the original NASA flight plan (opens in new tab). (That flight plan was aborted due to an in-flight emergency April 13, forcing a safe return to Earth on April 17.)

On April 12, some banter between the spacecraft and Mission Control talked about Swigert’s tax dilemma, which he also disclosed to Lovell (opens in new tab) shortly before the call, according to the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Magazine.

Related: 50 years ago, Apollo 13’s Jack Swigert flew to the moon, but forgot something big. Taxes.

(opens in new tab)

“Uh-oh, have you guys completed your income tax?” came the call from Mission Control, according to a transcript of communications (opens in new tab).

Without missing a beat, Swigert radioed, “How do I apply for an extension?” As ground controllers laughed, he added, “It ain’t too funny; things kind of happened real fast down there, and I do need an extension.”

Swigert, still hearing laughter from Mission Control, said he was serious and feared consequences from the IRS after he emerged from the standard quarantine NASA imposed on moon crews: “I may be spending time in another quarantine besides the one that they [NASA] are planning for me.”

Capcom Joe Kerwin assured Swigert they would “see what we can do,” but Lovell continued to rib his colleague: “Is it true that Jack’s income tax return was going to be used to buy the ascent fuel for the LM [lunar module]?”

“Well, considering that he’s a bachelor and hasn’t got that [marriage] deduction to take, yes,” Kerwin joked. Swigert pleaded once again that this was serious, and Kerwin promised he would have astronaut Tom Stafford investigate the matter.

Five hours later, Kerwin had relief to report: “Jack, the preliminary indications are that you can get a 60-day extension on filing your income tax if you’re out of the country.” (A 2014 update from CNN, however, says astronauts may not be eligible (opens in new tab) for that provision any more.)

Related: Apollo 13 timeline: The hectic days of NASA’s ‘successful failure’ to the moon

(opens in new tab)

The tax incident was immortalized in the 1995 Apollo 13 movie based upon the events of the real-life mission. In the film, the crew is participating in a fictionalized in-space television broadcast minutes before the explosion that derailed the mission. (The broadcast happened, which you can see here (opens in new tab), but with no tax discussions.)

The Hollywood version of Swigert (played by Kevin Bacon) asks if anyone from the IRS is watching the Apollo 13 crew on television: “I forgot to file my 1040 return, and I meant to do it today,” he says.

“That’s no joke! They’ll jump on him!” quips a mission controller in the movie, watching Swigert’s face on television.

Much later in the film, Mission Control radios personal assurance to Swigert on behalf of the office of President Richard Nixon: “He’s going to grant you an extension on your income taxes since you are most decidedly out of the country.”

References

Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. (n.d.) Apollo 13 Transcripts. https://history.nasa.gov/alsj/a13/a13trans.html (opens in new tab)

Klesius, Mike. “240,000-mile Filing Extension.” Smithsonian Air and Space Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/240000-mile-filing-extension-135438931/ (opens in new tab)

NASA. (2011). Astronaut Selection and Training. https://www.nasa.gov/centers/johnson/pdf/606877main_FS-2011-11-057-JSC-astro_trng.pdf (opens in new tab)

NASA History. (1970, April 2.) Press Kit: Project Apollo 13. https://history.nasa.gov/afj/ap13fj/pdf/a13-press-kit.pdf (opens in new tab)

The Space Archive, via NASA. (2020, March 6). Apollo 13 TV Transmission LM Tour. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6T3M9WTTiY (opens in new tab)

U.S. Office of Personnel Management. (2023). Salary Table 2023-GS. https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/pay-leave/salaries-wages/salary-tables/pdf/2023/GS.pdf (opens in new tab)

U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2023.) How Much Has the U.S. Government Spent This Year? https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/federal-spending/ (opens in new tab)

Yan, Sophia. (2015, Feb. 13). “Nobody Escapes U.S. Taxes — Even Astronauts.” CNN Money. https://money.cnn.com/2014/12/07/pf/astronaut-taxes-irs/index.html (opens in new tab)

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of “Why Am I Taller (opens in new tab)?” (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or Facebook (opens in new tab).