Go outside tonight and look at Jupiter shining brightly in the south. Now look just to its right side and go 235 trillion miles (378 trillion kilometers) into the cosmos. Here between the head of Pisces and the side of Aquarius is a nondescript star called TRAPPIST-1, an ultra-cool red dwarf discovered in 1999.

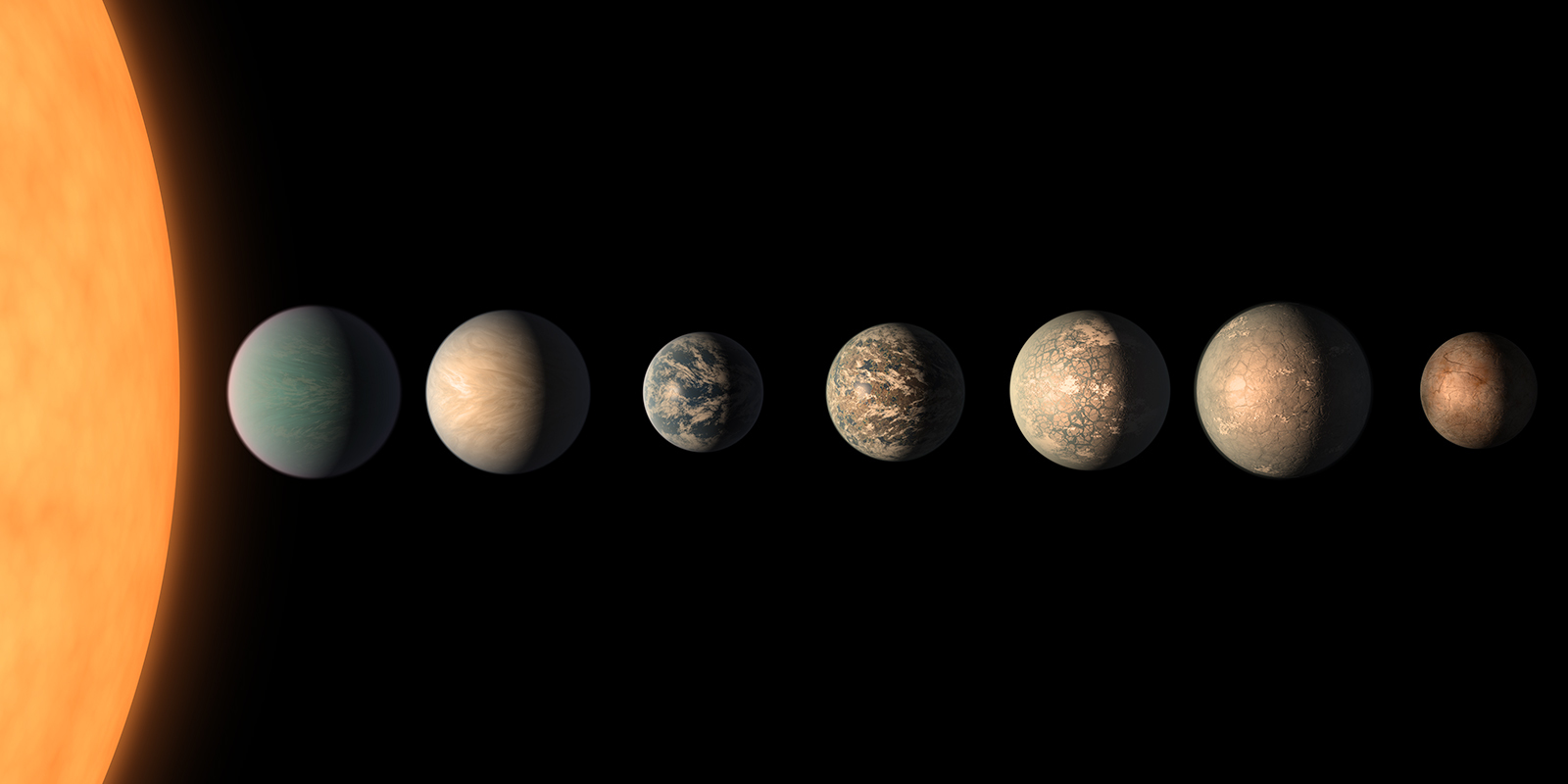

TRAPPIST-1 was mostly forgotten until 2017, when NASA announced that it hosted the most Earth-sized planets found in the habitable zone of a single star to date. Exoplanet-hunters have been obsessed with TRAPPIST-1 ever since. At last count, the neighborhood held seven planets, nearly matching the eight found in our own solar system. But is TRAPPIST-1 a mirror or a mirage? Could it contain Earth-like planets — and possibly life — or does its passing resemblance to the solar system hide alien planets with inhospitable conditions?

Cue the James Webb Space Telescope (Webb or JWST), which exoplanet astronomers are hoping will reveal the true nature of this unique planetary system. Using its ability to characterize an exoplanet’s atmosphere, recently proven at WASP-96b, JWST is looking at each of the seven planets in its first year of operations, and we’re on the cusp of the first results.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope’s best images of all time (gallery)

Revealing TRAPPIST-1

A mere 39 light-years from Earth — a close neighbor in cosmic terms — the TRAPPIST-1 star is not sun-like. The star is about a 10th of the sun’s mass and about as wide as Jupiter. However, it’s what orbits it that gets exoplanet-hunters excited. Three planets were discovered in 2016 by a Belgian telescope at La Silla Observatory in Chile called TRAPPIST — the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope.

That discovery was more than confirmed by NASA’s now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope in 2017. “The Spitzer Space Telescope played a gigantic role in uncovering the TRAPPIST-1 system and JWST is the follow-up,” Nikole K. Lewis, an exoplanet scientist at Cornell University, told Space.com.

Spitzer spent 1,000 hours staring at TRAPPIST-1 and was able to tell us that there were seven planets in the system. Spitzer also measured both the mass and radius of each world, which allowed basic calculations of the planets’ densities, all of which are similar to Earth’s. Astronomers have been on tenterhooks ever since.

Examining their atmospheres

“We know the TRAPPIST-1 planets are made of stuff just like Earth,” Lewis said. “So they might have Earth-like atmospheres.”

Lewis co-led a team that in 2018 used the Hubble Space Telescope to scan the planets’ atmospheres. “We didn’t see any signal of atmospheres, but we know that they don’t have big fluffy hydrogen and helium-rich atmospheres that you might expect,” Lewis said. Such atmospheres are associated with gas giant planets like Saturn and Jupiter.

But Hubble had reached its limits. Cue JWST. “The TRAPPIST system has long been on the JWST plan, and because we’ve known about it for six years we were able to really make sure that we were observing it to the best of JWST’s abilities,” Lewis said.

TRAPPIST-1: a solar system 2.0?

And astronomers have spent that time learning as much as possible about the seven TRAPPIST-1 worlds. In 2018, a study suggested its planets were rocky and that some could be wetter than Earth. In 2021 another study argued that they were likely rocky, although less dense than the planets in our solar system.

The TRAPPIST-1 system likely isn’t much like the solar system. Although four of the seven planets occupy the star’s habitable zone — close enough to be warm enough to host liquid water — all orbit their star closer than Mercury does the sun.

Given that the star is much dimmer than our sun, that may not affect temperatures too much, but it drastically affects the conditions on the planets. For example, the closest planet, TRAPPIST-1b, orbits its star in 1.9 Earth days. That’s a very short year. On TRAPPIST-1h, the farthest, a year takes just shy of 19 days. What’s more, all of the planets are likely tidally locked, much like the moon is to Earth, so only one side ever gets daylight.

Despite these differences, TRAPPIST-1 remains the top exoplanet target for JWST because of its diversity of rocky planets. And although it’s one of the most-studied planetary systems, scientists still think TRAPPIST-1 has a lot more secrets to reveal.

TRAPPIST-1 in transit

TRAPPIST-1 the only star system we know with seven potentially Earth-like planets, but it’s far from being the closest planetary system. That honor goes to Proxima Centauri, at 4.24 light-years away from Earth.

So why the fascination with TRAPPIST-1, which is 10 times farther? “Proxima does not transit and it’s transiting exoplanets that we need,” Lisa Kaltenegger, an astronomer at Cornell University, told Space.com. Our line of sight to the TRAPPIST-1 system is perfect, and our telescopes can see its seven planets crossing the disk of the star.

“The closest transiting planets give us the most looping signal, which is why TRAPPIST-1 is one of our favorite systems,” Kaltenegger said. Astronomers can watch the TRAPPIST-1 planets go round and round.

JWST’s first look

Can JWST find out what’s in the atmospheres of these seven rocky exoplanets? Webb’s NIRSpec instrument makes it the only telescope capable of identifying the signatures of molecules such as methane, carbon dioxide and oxygen — possible signs of life on the surface and clues to the makeup of a planet’s atmosphere. After promising work decoding the gases present in the atmosphere of WASP-39b, last week astronomers finally got a glimpse of JWST’s first look at the TRAPPIST-1 system.

It’s not yet been peer-reviewed or published, but at a conference at JWST’s HQ — the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore — on Dec. 13, scientists discussed the telescope’s initial data from its observations of TRAPPIST-1g, the second-farthest planet from the star.

Björn Benneke, an astronomer at the University of Montreal in Canada, showed that TRAPPIST-1g doesn’t have a hydrogen-rich atmosphere. Olivia Lim, a Ph.D. student at the University of Montreal, also presented a poster with similar results for TRAPPIST-1b (part of a reconnaissance program of all TRAPPIST-1 planets) as did Alexander Rathcke, an astronomer at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, for observations of TRAPPIST-1c.

So, no headline-grabbing discoveries about any TRAPPIST-1 planets in JWST’s first observations.

What’s next for JWST?

But don’t be disheartened by the lack of revelations in these early results. They’re about reconnaissance — understanding how to best use JWST’s precision and its various instruments.

“Those first observations are going to get us to the same level we got to with Hubble, more or less, but we’ll know how to use the instruments we want to use,” Lewis said. “It will take multiple observations with JWST to build up the signals that we need, and with JWST’s longevity we can just keep revisiting and learning more.”

Lewis will study TRAPPIST-1e. “It’s the one in the middle of the habitable zone that’s closest to the size of Earth,” she said.

Remember, this research is just about the planets’ atmospheres. “We don’t get to start asking about aliens probably for a few cycles!” Lewis said.

But exoplanet science is not done in isolation. Lewis is working with the University of Montreal because their observations of TRAPPIST-1d and TRAPPIST-1f — two of the other planets in the habitable zone — will together make for a fascinating comparative sample.

“Having Venus, Earth and Mars in our own solar system has really informed us a lot about why Earth is habitable, about global warming and what could happen if Earth was slightly smaller,” Lewis said.

TRAPPIST-1’s fundamental future

One of the TRAPPIST-1 planets will go down in history as hosting the first detected atmosphere of an Earth-size planet beyond our solar system. The next few months, years and decades will see the TRAPPIST-1 system gradually revealed in exquisite detail. But as well as finding out the true nature of its seven Earth-size planets, expect to see the neighborhood used to conduct some fundamental exoplanet science.

“We will be able to examine the true influence of the star on a relatively Earth-like, rocky planet,” Kaltenegger said, “and we’ll be able to see if our concept of the habitable zone actually works in practice.”

All of this opportunity comes from the incredible characteristics of a remarkably close star system. “TRAPPIST-1’s planets are all roughly the same size, but they’re different distances from their stars so we can explore them and think about the processes that shape them,” Lewis said. “It’s like nature gave us this perfect laboratory experiment.”

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.