The full moon of July, also called the “Buck Moon” or “Thunder Moon,” will occur July 13, at 2:37 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time (opens in new tab) (1837 GMT on July 13); The moon will also reach perigee, the closest point in its orbit to Earth, at 5:06 a.m. that day, creating a “supermoon” — a full moon that appears slightly larger than normal.

It is the third of four supermoons in a row, according to NASA eclipse watcher Fred Espenak.

Observers in New York City will see the almost-full moon set at about 4:55 a.m. local time on July 13, according to timeanddate.com, and it will rise that evening at 9:00 p.m.

A full moon occurs when the moon is on the opposite side of the Earth from the sun. Earthbound observers see the moon reflect the sun’s light. Occasionally — anywhere from two to five times a year — the moon will pass into the Earth’s shadow, creating a lunar eclipse.

Related: What is today’s moon? Moon phases 2022

The moon’s orbit also isn’t a perfect circle, so every few months the full moon coincides with perigee. Being closer, the moon appears about 10% larger than normal to the eye, though unless you are very observant you won’t notice. Ordinarily, the moon is an average of 30 minutes of arc — a half a degree, or approximately the width of a fingernail at arm’s length. When at perigee that goes up to 33 minutes of arc. The moon will be 222,000 miles (357,280 kilometers) away, against an average of 238,900 miles (384.500 km).

The local time of a full moon depends on one’s time zone since a full moon is counted using the moon’s position relative to the Earth’s center rather than a given point on the surface. You’ll want to check out a skywatching app like SkySafari or software like Starry Night to check for location-specific times. Our picks for the best stargazing apps may help you with your planning.

The moon’s altitude in the sky, however, depends on one’s latitude, and that affects the rising and setting times. So, for example, the full moon rises in New York on July 13 at 9:00 p.m. local time and will reach an altitude of 23 degrees at 1:33 a.m. on July 14, when it crosses the meridian. In Miami it rises at 8:39 p.m., crosses the meridian at 1:59 a.m. and will be 38 degrees high, whereas in Quito, Ecuador, moonrise is at 6:36 p.m. local time, the meridian crossing is at 12:52 a.m. July 14, and the maximum altitude is 67 degrees.

The difference is not only that from different latitudes one has a different point of view, it’s also because the moon’s orbit and the sun follow a path called the ecliptic, which is the plane of the Earth’s orbit projected on the celestial sphere. If one could see that line painted on the sky, the angle it makes at sunset in the Northern Hemisphere summer months would be shallower than during the winter months (and the reverse would be true in the Southern Hemisphere). During Northern Hemisphere summers, the full moons will be lower in the sky towards the south, because the plane of the ecliptic is lower. In the Southern Hemisphere — the full moons in June, July and August, which is their winter — will be higher up, and towards the north.

The lunar orbit is also tilted by about 5 degrees to the ecliptic. That’s why we don’t get a lunar eclipse every full moon and a solar eclipse every new moon. Generally, any given place on Earth will see a lunar eclipse every two to three years.

When observing the full moon through binoculars or a telescope be prepared for a lot of glare — the moon is so bright that through larger telescopes one might even need filters to give the surface features some contras. There is no danger to one’s eyes, but details can be harder to see because there are few visible shadows in the central part of the lunar disk — if an astronaut were there the sun would be directly overhead. Observing the moon a few days prior to or a few days after the full phase when there are shadows makes spotting surface features easier.

Hoping to capture a good photo of the full moon? Our guide on how to photograph the moon has some helpful tips. If you’re looking for a camera, here’s our overview of the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography. As always, our guides for the best telescopes and best binoculars can help you prepare for the next great skywatching event.

Saturn conjunction and visible planets

(opens in new tab)

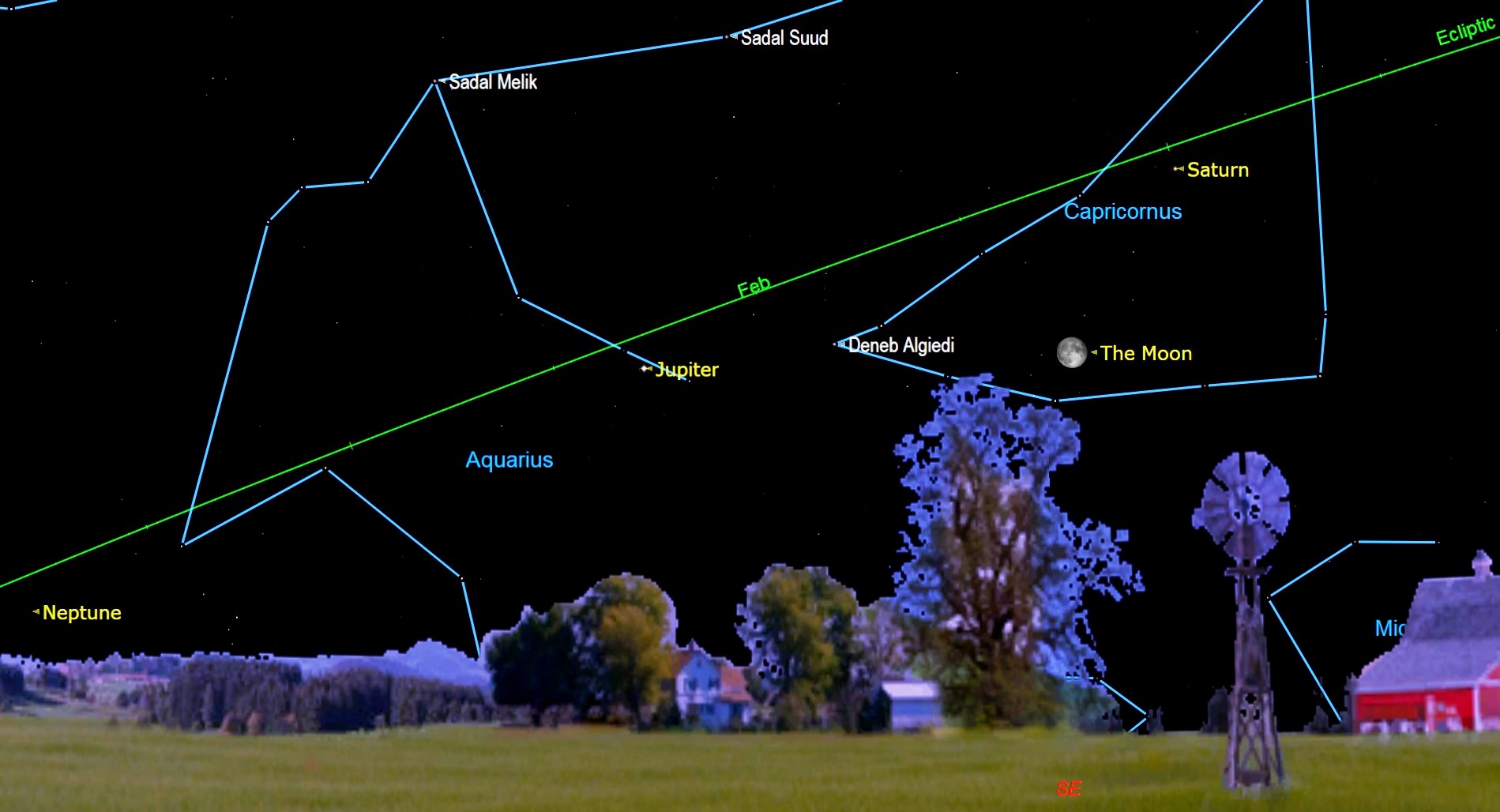

On July 15 at 4:16 p.m. Eastern Time the waning gibbous moon will be in conjunction with Saturn, according to In-The-Sky.org. and will pass about 4 degrees (eight lunar diameters) south of the planet, so for Northern Hemisphere observers, the planet will be to the left of the moon before midnight as they rise and to the right after local midnight. From New York City Saturn rises at 9:59 p.m. local time while the moon follows at 10:25 p.m. By that point the conjunction itself will have passed but the two will be close together still; both in the constellation Capricornus, the water goat. The stars of Capricornus itself will be largely overwhelmed by the moon, so Saturn will be easier to spot as a yellow-white, steady medium-bright “star.” At their highest, they will be 34 degrees above the horizon, at 3:09 a.m. local time.

The moment of conjunction will be visible if one is in Europe, Africa or western Asia; for example, in London, the conjunction will happen at 9:16 p.m. local time on July 15; in Cape Town, it will be at 10:16 p.m., and in New Delhi, it will be at 1:46 a.m. on July 16, and in Bangkok, the conjunction is at 3:16 a.m. local time.

How easy the moon and Saturn will be to spot depends largely on latitude. From London, the pair won’t get more than 23 degrees high (at 3:14 a.m. local time on July 16). In Cape Town, they will be 70 degrees above the northern horizon at 3:00 a.m. local time. Meanwhile, in New Delhi, the maximum altitude is 46 degrees at 2:31 a.m. local time.

On the night of the full moon itself, four of the five naked-eye planets will form a line across the sky for observers in mid-northern latitudes. (Mercury will be lost in the solar glare at sunrise). Saturn is the first to rise, at 10:04 p.m. local time in New York City, followed by Jupiter at 11:50 p.m. Mars rises at 1:03 a.m. July 14, and Venus rises at 3:39 a.m. By about 4:30 a.m. Venus is about 8 degrees above the northeastern horizon, and looking to the right (towards the south) one will see Mars, at about 38 degrees high. Jupiter will be about 46 degrees high nearly due southeast, and Saturn will be just west of south at about 31 degrees altitude.

For Southern Hemisphere sky watchers, the planets will all be higher, and the sun rises later as it is winter there. In Cape Town, for example, the sun sets on July 13 at 5:54 p.m. and does not come up until 7:49 a.m. local time on July 14. Saturn rises July 13 at 8:13 p.m. local time. Jupiter rises at 11:56 p.m., and Mars rises a 2:14 a.m. July 14. and Venus at 6:14 a.m. In this case by 7 a.m. Venus will be in the northeast, 10 degrees above the horizon. Mars will be to the left and some 44 degrees high, nearly due north, while Jupiter will be slightly west of north and 50 degrees up. Saturn will be towards the west, about 33 degrees high.

In July, Northern Hemisphere summer constellations will be in full view all night, but the moon’s brightness will wash out most fainter stars. The Summer Triangle — Deneb, Altair and Vega — will be approaching the zenith in the eastern sky towards midnight, and Antares, the brightest star in Scorpio, will also be reaching its highest point in the sky.

Looking roughly northwest at about 10:30 p.m. the sky will be fully dark, and one of the first stars to be visible in that area is Arcturus, the brightest star in Boötes, the herdsman. If one turns a bit to the right (north) one can spot the Big Dipper, which will have its “bowl” facing to the right. The two stars on the “bottom” side of the bowl will point to Polaris, the pole star. In the other direction, one can trace an arc along the handle and “arc to Arcturus” and then keep going to hit Spica, the brightest star in Virgo, low in the southwest.

Turning left (south) one will see Antares, the “heart” of Scorpio, the legendary creature that killed Orion the hunter (who appears in winter). Just above Scorpio, one will see a tall, roughly rectangular shape made by some fainter stars; this is Ophiuchus, the healer who brought Orion back from the dead after Scorpio killed him. Ophiuchus is more difficult to see from urban areas, as the stars are fainter than Antares. But if one turns to the left and upwards, one comes to Altair, the brightest star in Aquila the Eagle, and the southernmost of the three stars of the Summer Triangle. Looking north (upwards) from Altair one will come to Deneb and Vega — Vega will be closer to the Zenith.

How the Buck Moon got its name

(opens in new tab)

Native peoples in the Americas had various names for July’s full moon; the names reflect that in the Northern Hemisphere it is summer. “Traditionally, the full moon in July is called the Buck Moon because a buck’s antlers are in full growth mode at this time,” according to the Old Farmer’s Almanac (opens in new tab). “This full moon was also known as the Thunder Moon because thunderstorms are so frequent during this month.”

The name “Thunder Moon” was adapted from native peoples in what is now the eastern United States, where summer is thunderstorm season. However, the July full moon had other names. According to the Ontario Native Literacy Coalition, the Ojibwe call it the Raspberry Moon, while Cree called it the Feather Molting Moon, as some birds start to molt in the summer.

The Māori of New Zealand use a lunar calendar called the maramataka (opens in new tab) which measured months between successive new moons. The June-to-July lunar month (which this year spans the new moons from June 21 to July 20) is called Hōngongoi, or “man is now extremely cold and kindles fires before which he basks,” according to the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. This lunar month was, to the Māori, the second month of the year.

The Chinese lunar calendar marks July’s full moon as occurring in the sixth month, Héyuè, or Lotus Month, when the eponymous flowers bloom.

Muslims celebrate Eid-Al-Adha starting July 9, in a festival that lasts about four days, ending near the day of the full moon. Eid-Al-Adha honors Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son to God as outlined in both the Bible and the Qu’ran.

Editor’s Note: If you capture an amazing night sky photo and want to share it with Space.com for a story or gallery, please send images and comments to [email protected].

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook.