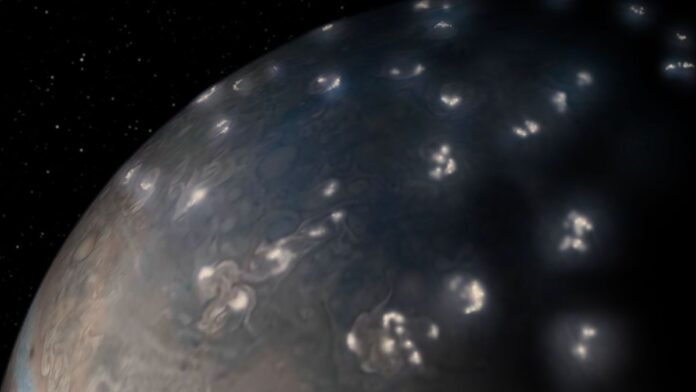

Lightning crackles to life and evolves on Jupiter the same way as it does on Earth, a new study finds.

Jovian lightning, which occurs as frequently as the phenomenon does on Earth, was first spotted by NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft over 40 years ago. Back then, the well-traveled probe picked up faint radio signals spanning several seconds — nicknamed whistlers — that are expected from lightning strikes. At the time, these bolts of electricity certified Jupiter to be the only other planet besides Earth known to flaunt lightning strikes. Their evolution on the gaseous world, however, has puzzled scientists for decades.

Now, a team studying five years worth of data from NASA’s Juno spacecraft, which has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016, has found that Jovian lightning takes place in the same “step-wise” way as it does on Earth. The new observations show that despite the two planets being polar opposites in their sizes and structures — our rocky planet is much smaller than Jupiter and has a solid surface, which the gas giant lacks — both host the same kind of electrical storms.

Related: Jupiter, the solar system’s largest planet (photos)

On Earth, lightning originates inside turbulent clouds, whose upward winds lift water droplets and freeze them into ice, while downward winds push those frigid blobs back to the bottom of the clouds. Where the falling ice meets the rising water drops, electrons are stripped off from the former, resulting in a cloud whose base is negatively charged and whose top is positive, separated by insulating air. When these charges build up, the well-known lightning bolt zaps within a cloud or sometimes from a cloud’s base to the ground. Previous research had found that the same process unfolds in the Jovian atmosphere.

Though lightning strikes on Earth look like long, smooth bolts from afar, researchers know that each spark of electricity is in fact made of distinct steps. Each step beams out isolated radio emissions, whose detection is often the only way to understand what’s going on inside thunderclouds.

“It was not clear if such stepping process also occurs in Jovian clouds,” Ivana Kolmašová, a senior research scientist at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics of the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague and a lead author of the new study, told Space.com.

That’s because previous spacecraft that studied lightning on Jupiter — NASA’s Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, Galileo and Cassini — did not have instruments sensitive enough to capture the radio signals in granular detail. The Waves instrument onboard Juno, however, collected 10 times more radio emissions than its predecessors. It did so by picking up lightning signals separated by as close as one millisecond, which revealed step-like behavior in which air in Jovian clouds is being charged up and forming lightning — the same way it does on Earth.

“The most challenging and also the most time-consuming part of the work was the search for lightning signals in the records of the Waves instrument,” Kolmašová said.

On Jupiter, one such step of lightning could span anywhere between several hundred to a few thousand meters long, although it is hard to confirm with existing Juno data, Kolmašová and her team wrote in the new study.

While the new findings shed more light on the early lightning processes on Jupiter, much remains to be revealed. For example, while Earth and Jupiter lightning strikes in similar ways, where these phenomena occur is wildly different on both worlds. On the gas giant, a large chunk of the thunderstorms have been found in midlatitudes and higher, and in polar regions. They are absent at the huge planet’s equator, which is opposite to thunderstorms back home, where regions close to the equator report the most lightning strikes.

“We have nearly no lightning activity close to poles on the Earth,” Kolmašová told Space.com. “It means that conditions for a formation of Jovian and terrestrial thunderclouds are probably very different.”

The lightning on Jupiter is also distributed lopsidedly, with its northern hemisphere hosting more strikes than its southern half. The reason for this, however, is not yet clear.

“We also don’t know why we have not seen any lightning coming from the [Great] Red Spot up to now,” she added.

This research is described in a paper published Tuesday (May 23) in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @skuthunur. Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.