This week brings us the return of the famous Leonid Meteor Shower, a meteor display that two decades ago brought great anticipation and excitement to sky watchers around the world.

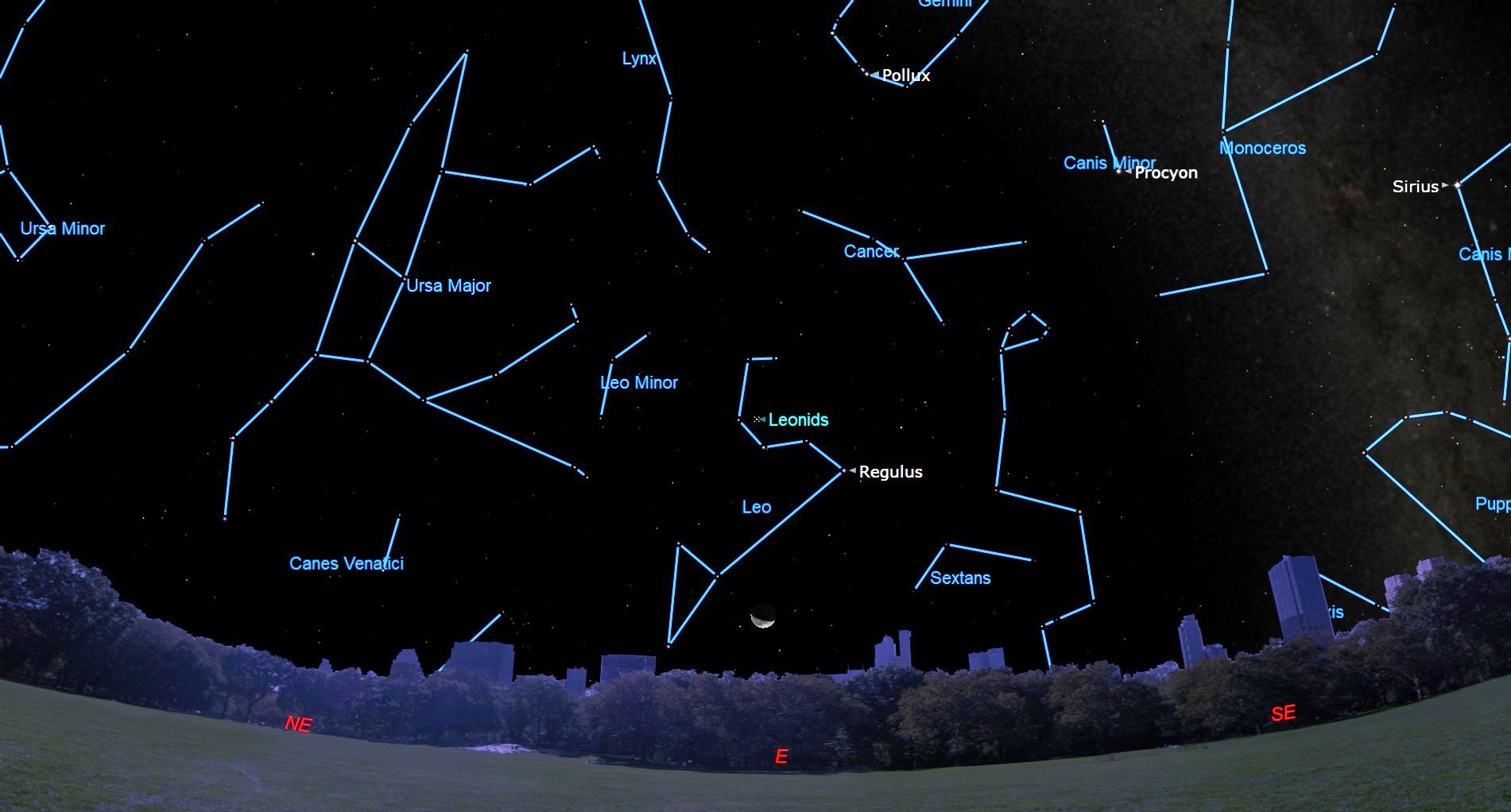

Solely from the standpoint of viewing circumstances, this will be a favorable year to look for these meteors, since the moon will be a waning crescent phase and should not provide too much of a hindrance to meteor watchers who will be looking for these ultrafast meteors, which dart from the Sickle of Leo (from where the meteors get their name).

Be sure to keep this in mind: at this time of year, meteor watching can be a long, cold business. Expect the ambient air temperature to be far below what your local radio or TV weathercaster predicts.

Related: Leonid meteor shower 2022: When, where & how to see it

Leonid meteors: Debris from the Tempel-Tuttle comet

The Leonid meteors are debris shed into space by the Tempel-Tuttle comet, which swings through the inner solar system at intervals of 33.25 years. With each visit the comet leaves behind a trail of dust in its wake. Lots of the comet’s old dusty trails litter the mid-November part of Earth’s orbit and the Earth glides through this debris zone every year. Occasionally we’ll pass directly through an unusually concentrated dust trail, or filament, which can spark a meteor storm resulting in thousands of meteors per hour. That’s what happened in 1999, 2001 and 2002. Since Tempel-Tuttle passed the Sun in 1998, it was in those years immediately following its passage that the Leonids put on their best show.

Since then, the comet — and its dense trails of dust — all receded far beyond Earth’s orbit and back into the outer regions of the solar system. Tempel-Tuttle arrived at the far end of its elliptical path out near the orbit of Uranus in 2014. As a result, Leonid activity has been rather sparse in recent years. The comet has since turned around and is now slowly approaching the inner solar system, though it’s still very far away. It’s expected to be closest to the sun again in 2031.

So, it would seem that odds are that this year there is little, if any chance of any unusual meteor activity. The dust from Tempel-Tuttle spangles the sky for a few nights every year in mid-November and this year, the traditional peak is expected on Nov. 18. But realistically — at best — we would not expect to see more than 5 or 10 Leonids during an hour’s watch.

Yet if two reputable meteor scientists are correct, this year will be atypical. These scientists have produced various models of the Leonid stream and all of them are indicating that the Earth will intersect a few “rivers of rubble” left behind by comet Tempel-Tuttle.

An uncertain forecast

In the 2022 “Observer’s Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada,” meteor experts Margaret Campbell-Brown and Peter Brown, indicate that this year’s peak activity should occur on at 7 p.m. EST (0000 GMT on Nov. 18) on the evening of Nov. 17. This is the moment when the Earth will be passing closest to the orbit of the long-departed comet, and when our planet seemingly is most likely to encounter some residual comet material. This time is highly favorable for those in central and western Europe and western Asia. But in contrast, for North American observers, Leo will still be below the horizon; they will have to wait until later after midnight to catch a view of the Leonids.

The main show is expected on the morning of Saturday (Nov. 19). Model calculations by Russian meteor expert Mikhail Maslov and his Japanese counterpart Mikiya Sato show an approach of a dust trail shed by Tempel-Tuttle in 1733, interacting with Earth on this date. Maslov gives 06:00 UT, Sato predicts 6:25 UT. This translates to 1:00 a.m. to 1:25 a.m. EST (0600 GMT to 0625 GMT), excellent timing for eastern North America, where the Sickle of Leo will be situated about one-third up in the eastern sky and the moon will lie just below the horizon. Earth will cross through the 1733 stream at a distance of 89,000 miles (143,000 km) from the center. Maslov adds that “Many of the meteors should be bright, an hourly rate of 250-300 seems possible despite the uncertainties.” Sato, however is much more conservative: “Hourly rates may reach 50+ because the model suggests that the dust tends to be less concentrated.”

Farther west, for those in the central time zone, the peak comes at 12:00 a.m. to 12:25 a.m. CST (1825 GMT), and the Sickle will be noticeably lower in the eastern sky. Across western North America, the only hope of sighting anything unusual might come from an “Earth grazer” — a meteor that skims horizontally through the upper atmosphere from a radiant near the horizon. Spectacular Earth-grazers are usually slow and bright, streaking far across the sky and still worth looking for. Otherwise, little or nothing of this enhanced activity will be visible because, unfortunately, Leo’s Sickle will either be sitting on the horizon or will have yet to rise.

There is one final possible Leonid surge on Nov. 21 at 15:00 UT, from debris shed by the comet in 1800. The timing favors Hawaii and eastern Asia.

How to watch the Leonids

Watching a meteor shower consists of lying back, looking up at the sky and waiting.

When you sit quite still, close to the rapidly cooling ground, you can become very chilled. You wait and you wait for meteors to appear. When they don’t appear right away, and if you’re cold and uncomfortable, you’re not going to be looking for meteors for very long! Therefore, make sure you’re warm and comfortable. A comfortable reclining lawn chair, heavy blankets, sleeping bags, pillows and cushions are essential equipment.

Warm tea, coffee or cocoa can take the edge off the chill, as well as providing a slight stimulus. It’s even better if you can observe with a companion (“shower” with a friend). That way, you can keep each other awake, as well as cover more sky.

Because the Leonids are moving along their orbit around the sun in a direction opposite to that of the Earth, they slam into our atmosphere nearly head-on, resulting in the fastest meteor velocities possible: 45 miles (72 km) per second. Such speeds tend to produce bright and colorful meteors with hues of white, blue, aquamarine and even green, which leave long-lasting streaks or trains in their wake.

So, for North American observers, the emphasis might be on quality, not quantity; for it would not be surprising if the numbers quoted above by Maslov and Sato fall far off the mark. But a few of those meteors, though visible for just a fraction of a second, might leave bright trails of ionized atoms in their wake that hang in the sky for many seconds — or possibly even minutes — as these tiny dust particles streak through our atmosphere at altitudes of 80 to 100 miles (130 to 160 km).

And seeing even just one such outstandingly bright meteor like that can make a cold early morning vigil worthwhile!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium (opens in new tab). He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine (opens in new tab), the Farmers’ Almanac (opens in new tab) and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).