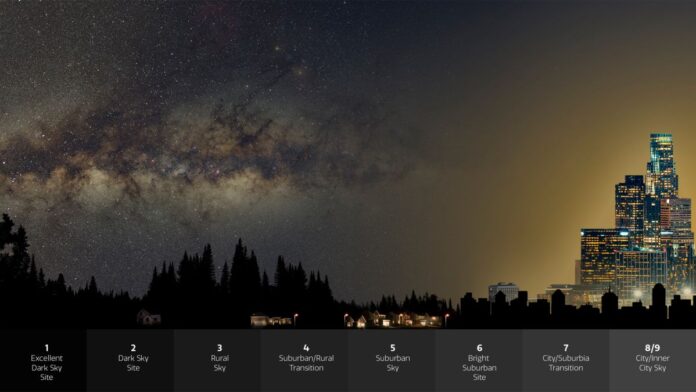

Light pollution is brightening up the night sky so fast that stars are virtually disappearing in front of sky-watchers’ eyes, a new study has revealed.

Where 18 years ago, a star gazer would see on average 250 specks of light illuminating the darkness overhead. Today, only 100 would be visible, according to the study that relied on information from thousands of citizen scientists all over the world.

The reason behind this unprecedented star loss is the increase in light pollution, the effect of artificial urban lightning that, according to the study, leads to an average 9.6% global annual rise in the brightness of the sky. This pace of sky-brightening is quite a bit faster than satellite measurements have indicated previously, the study’s authors said in a statement (opens in new tab).

The sky is brightening up at a different rate in different parts of the world. In Europe, the pace appears slightly slower at 6.5% per year, whereas in North America the night glow of the sky increases by 10.4% every year, the study found.

Related: Challenge for astronomy: Megaconstellations becoming the new light pollution

“The rate at which stars are becoming invisible to people in urban environments is dramatic,” Christopher Kyba, of the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences and lead author of the study, said in the statement.

The study was conducted by researchers from the GFZ German Research Center for Geosciences, the Ruhr-Universität Bochum and the US National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab. The analysis, dubbed the “Globe at Night” Citizen Science Project, included 50,000 naked eye night sky observations made by volunteers between 2011 and 2022 .

The lack of darkness at night is concerning for far more people than just professional astronomers and astronomy enthusiasts. According to Constance Walker, co-author of the study and head of the Globe at Night project of NSF’s NOIRLab, the unceasing exposure to light affects all humans as well as animals living in affected regions.

“Skyglow affects both diurnal [active during the day] and nocturnal animals and also destroys an important part of our cultural heritage,” Walker said in the statement.

The nighttime glow of the sky has not previously been measured globally, the researchers said, but estimates exist based on satellite measurements. Those measurements, however, have previously indicated that the increase in light pollution has plateaued and is even mildly decreasing in the most affected areas in Europe and North America. The new findings show that these earlier estimates were likely wrong.

“Satellites are most sensitive to light that is directed upwards towards the sky. But it is horizontally emitted light that accounts for most of the skyglow,” Kyba said. “So, if advertisements and facade lighting become more frequent, bigger or brighter, they could have a big impact on skyglow without making much of a difference on satellite imagery.”

On top of that, satellite sensors are less sensitive to LED lighting that has become more common in recent years, which glows in hues of blue, compared to the orange-glowing sodium vapor lamps that were dominant in the past.

“Our eyes are more sensitive to blue light at night, and blue light is more likely to be scattered in the atmosphere, so it contributes more to skyglow,” Kyba said. “But the only satellites that can image the whole Earth at night are not sensitive in the wavelength range of blue light.”

The researchers noted that one shortcoming of the study is that it didn’t have enough data from the developing world where changes may be happening at an even faster rate.

The study (opens in new tab) was published on Thursday (Jan. 19) in the journal Science.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.