Rocks found right here on Earth could help solve the mystery of what happened to Mars’ atmosphere.

Thanks to our hard-working Mars rovers, we know that there once was liquid water on our neighboring planet, which means the planet once had an atmosphere that kept it much warmer. But we know precious little about how that atmosphere formed — and how it disappeared. Now, thanks to some rocks from Duluth, Minnesota, scientists have a new theory.

It turns out that rocks from Duluth have a similar iron-rich mineral composition to rocks on Mars. Through testing, researchers then discovered that the process of serpentinization in these iron-rich rocks — that is, when rocks from Earth’s mantle come into contact with water and create hydrogen — is five times more robust than other types of rocks. When rocks release hydrogen through serpentinization, that hydrogen enters the atmosphere, where it combines with other gases to create a greenhouse effect — something that’s necessary to keep a planet habitably warm.

Related: New Mars photo reveals scars from Red Planet’s ancient past

“It also produces unique minerals and reduced organic compounds that could then fuel ecosystems and combine with other ingredients to form the building blocks of life,” Dr. Benjamin Tutolo, an associate professor in geoscience at the University of Calgary who served as lead author on a paper about the findings, said in a statement (opens in new tab).

Most of the geological processes on Mars have an analog that takes place here on Earth. However, the type of serpentinization that would have taken place on ancient Mars according to this theory is not commonplace on Earth. “So, understanding those rocks they’ve discovered at the base of Jezero Crater is going to require viewing through the lens of our new results from the Duluth Complex in Minnesota, of all places,” Tutolo said.

Though we haven’t yet brought Mars rocks to Earth which would allow scientists to confirm this theory, NASA’s Curiosity rover has given researchers a leg up. “The coolest thing about Curiosity Rover is that it has the ability to analyze minerals with its in situ laboratory. It has shown some evidence of serpentinization already there,” said Tutolo.

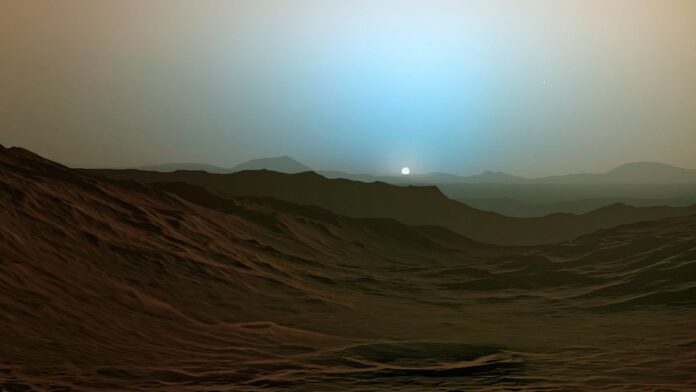

Next up for the researchers is figuring out why the Martian atmosphere evaporated, leaving the planet as cold and dry as it is today. The team is also excited to continue to study Mars geology for its potential implications on the formation of the solar system.

“The value of studying Mars is that it doesn’t have plate tectonics, all the rocks that are there have been there for 3.5 billion years at least. We have snippets of Earth that exist from that time, but the entirety of Mars exists from that time,” said Tutolo.” So, we can study things like, if the sun was cooler back then how did that affect the planetary surface? Why did biological evolution take so long to take off? Why did it take organisms so long to populate the continents? and so on.”

A paper on the team’s research was published on Feb. 3 in the journal Science Advances (opens in new tab).

Follow Stefanie Waldek on Twitter @StefanieWaldek (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).