If humans ever put boots on Mars, they need to go where the ice is first.

One problem: Astronaut crews don’t have the luxury to ring down to the hotel front desk for that Mars hospitality.

Work is ongoing to tease out where and at what depth extractable ice exists on the Red Planet. Not only is ice a key ingredient for helping to sustain human stays on that far-flung world, but ice is nice for science, including the search for life on Mars.

Related: The search for water on Mars (photos)

Planetary evolution

“Ice is, of course, useful for human exploration as drinking water or as rocket fuel. It can be split into oxygen and hydrogen and used as propellant to get home,” said Isaac Smith, an assistant professor at York University in Toronto, Ontario and a research scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in the United States.

“Having easy access to ice on Mars would mean saving billions of dollars for human missions that could economize their trip and save multiple launches and a lot of mass,” Smith told Space.com.

Smith and other scientists also care about ice because there is much to learn about the present and past climate of Mars. Such information can come from analyses of where the ice is now, how deeply it is buried, if there are layers in the ice, and what other impurities are present. Learning about this will help to better understand planetary evolution, Smith said.

Clear evidence

“We already know that there is ice on Mars and that it is distributed around the planet. The polar caps are visible from Earth, and we see clear evidence for ice as glaciers or from meteor impacts that expose ice that is buried,” Smith pointed out.

Gauging the distribution of that ice, the thickness and the impurities, scientists can put together a much better history, with fewer holes, of the last several hundred million years of Martian history, Smith added.

“We’re missing a lot of information about the ice that is just beneath the surface and ready to be observed,” said Smith.

Related: Water on Mars: Exploration and evidence

Shallow ice

Human exploration is in part driven by energy needs, specifically solar energy. Landing at high latitudes would mean easy access to ice, but then there is a half a year of darkness, Smith said. (A year on Mars is roughly 687 Earth days.)

“If humans want a permanent station, or even one that can be managed by robots until humans arrive,” Smith said, “then they need sunlight every day, and as much as possible. Because of that, we want to know how close to the equator we can get and still have accessible ice.”

Ice that is buried more than 30 feet (9 meters) deep or covered by giant boulders may be inaccessible with the technology that astronauts can lug to Mars.

“So, we’re searching for shallow ice that is accessible with shovels or bulldozers at low latitudes,” Smith said. “Lastly, we want to use ice that is in a safe landing zone far from steep slopes or high elevations, hence the need for a global search.”

Cold shoulder for an ice mapper

But the quest to carry out that Mars-wide survey appears to be, shall we say, on thin ice.

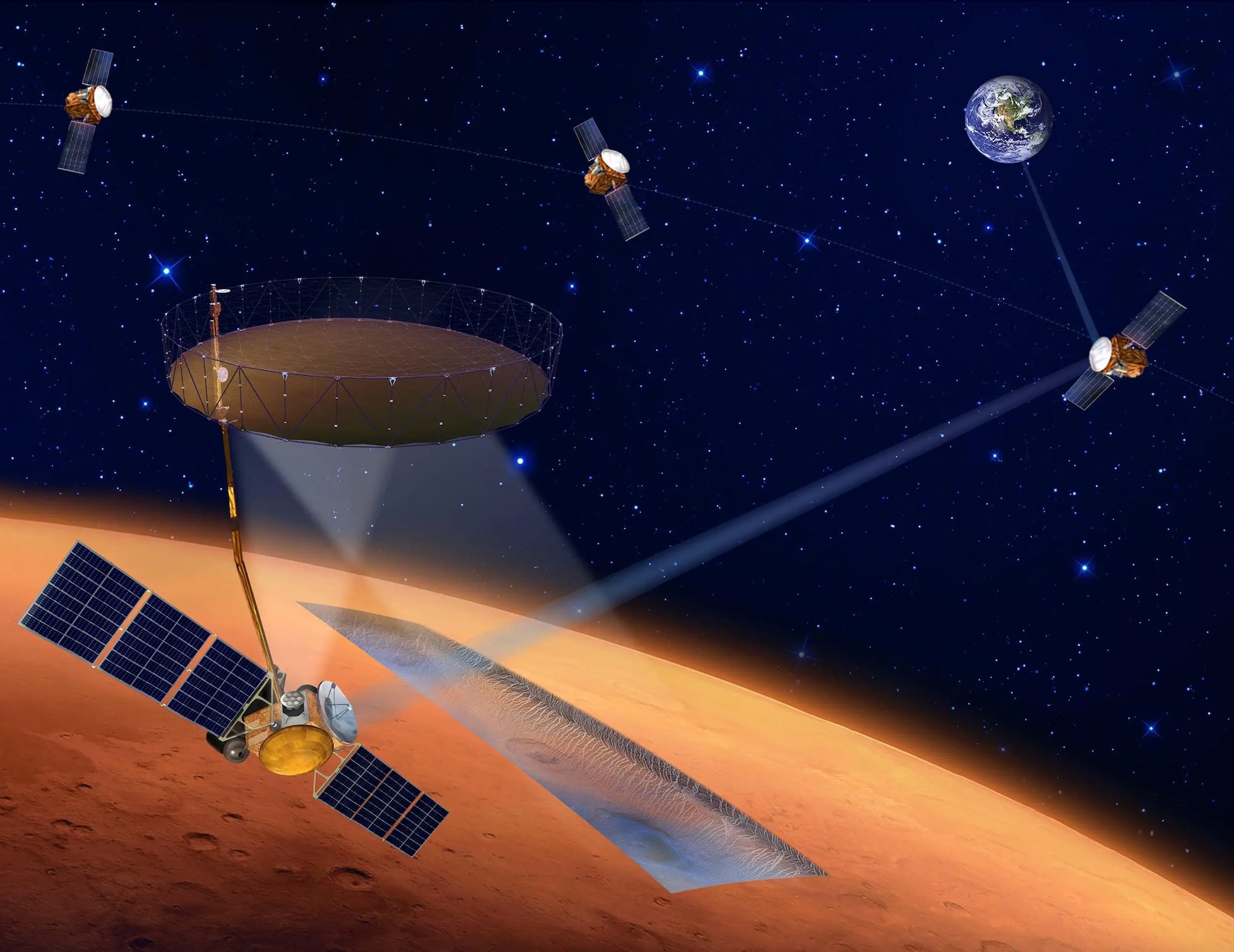

The International Mars Ice Mapper mission (I-MIM) was in the NASA budget for fiscal year 2022 but was removed the following year. That took the wind out of the sails of researchers eager to pinpoint icy resources on Mars.

Currently, I-MIM is in a holding pattern. But there is work going on behind the scenes to make a push to revive it, Smith said.

Representatives from the Canadian Space Agency and NASA continue to discuss I-MIM, with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency and Italy’s Agenzia Spaziale Italiana also involved.

Smith said he detects a hint of optimism that things might advance. “All of the agencies want this to work, but NASA’s participation seems critical for success, so it may hinge on what NASA can contribute,” he said.

Close to the equator

“You really want to understand where that ice is,” said Rick Davis, assistant director for science and exploration within NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. There’s also a need to characterize that ice, thereby enabling potential extraction of water, he said.

Attention is being turned to mapping water ice in the “reconnaissance zone” — mid- to low latitudes where human missions are operationally viable.

“Our error margins on determining where ice is are enormous. There’s no way you could guarantee a crew that they are actually drilling into ice, unless you go way far north on Mars,” Davis said.

“You want to be as close to the equator that have reliable ice deposits there,” he added. “It’s probably the one thing you really need to know before you attempt to send humans.”

Davis said that ice science is possibly the next frontier for Mars work, for ice cores give researchers a snapshot of history. The overlap for ice science — climate geology and astrobiology, as well as resource utilization on Mars — is very significant, he said.

“There’s a growing recognition that, when humans go, drilling into the ice is a very good use of astronauts. That drilling equipment benefits from a human in the loop, coring into ice and bringing those cores back to Earth,” Davis said.

Related: The big reveal: What’s ahead in returning samples from Mars?

Warm reception for a relict glacier

In March 2023, during the 54th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference held in The Woodlands, Texas, the discovery of a relict glacier near Mars’ equator was announced.

That finding is significant, as it implies that water ice was present in some surface locations near the equator even in recent times and might still be present at shallow depths today, said Pascal Lee, a planetary scientist with the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute and the Mars Institute.

Lee is the lead author of the study that focused on the relict glacier’s unearthing.

“It’s important to consider two things,” Lee told Space.com.”While we haven’t yet detected ice there, it could still be present, only buried at shallow depth because of how insulating and protective salt layers can be. At the Mars relict glacier site, we are looking at a surface crust of (sulfate) salts which could still be shielding glacier ice underneath.”

This scenario exists on Earth, Lee added, in the salt flats of the Altiplano, a high-elevation plateau. He cited a spot at Laguna Colorada in Bolivia where ancient ice islands are preserved under surface deposits of (carbonate) salts.

“The exceptional protective blanket that salt deposits can offer is usually not what’s considered in models of how water ice might survive on Mars. Models predict that water ice would be gone from shallow depths at low latitudes in generic types of soils,” said Lee. “But if you are dealing with overlying materials with exceptional insulating properties, like salt crusts, water ice could, in principle, survive over geological timescales even at Mars’ equator.”

Clean ice

Yet another point is that, if water ice is still present at the Mars relict glacier site, it may be relatively clean ice compared to ground ice detected elsewhere on Mars, Lee said, including at high latitudes, where ice is generally intimately mixed within the regolith.

“Glaciers form from precipitation of snow, so the water ice in a glacier is, by nature, relatively clean to start with,” Lee said. “Impurities get mixed in over time, and salts coating the glacier might seep in as well, but overall, you’d be dealing with massive water ice requiring little processing upon extraction, especially since the glacier is relatively young.”

Near-surface ground ice at higher latitudes on Mars, however, is generally going to be harder to extract and process into pure, clean water, he added.

As good as it gets

If water ice is confirmed to be present in the newfound relict glacier, it could be “as good as it gets” in terms of accessing, extracting and processing water on Mars, Lee said. “You’d be in a place that’s relatively warm year-round, has clean ice, buried under a thin soluble crust of sulfate salts.”

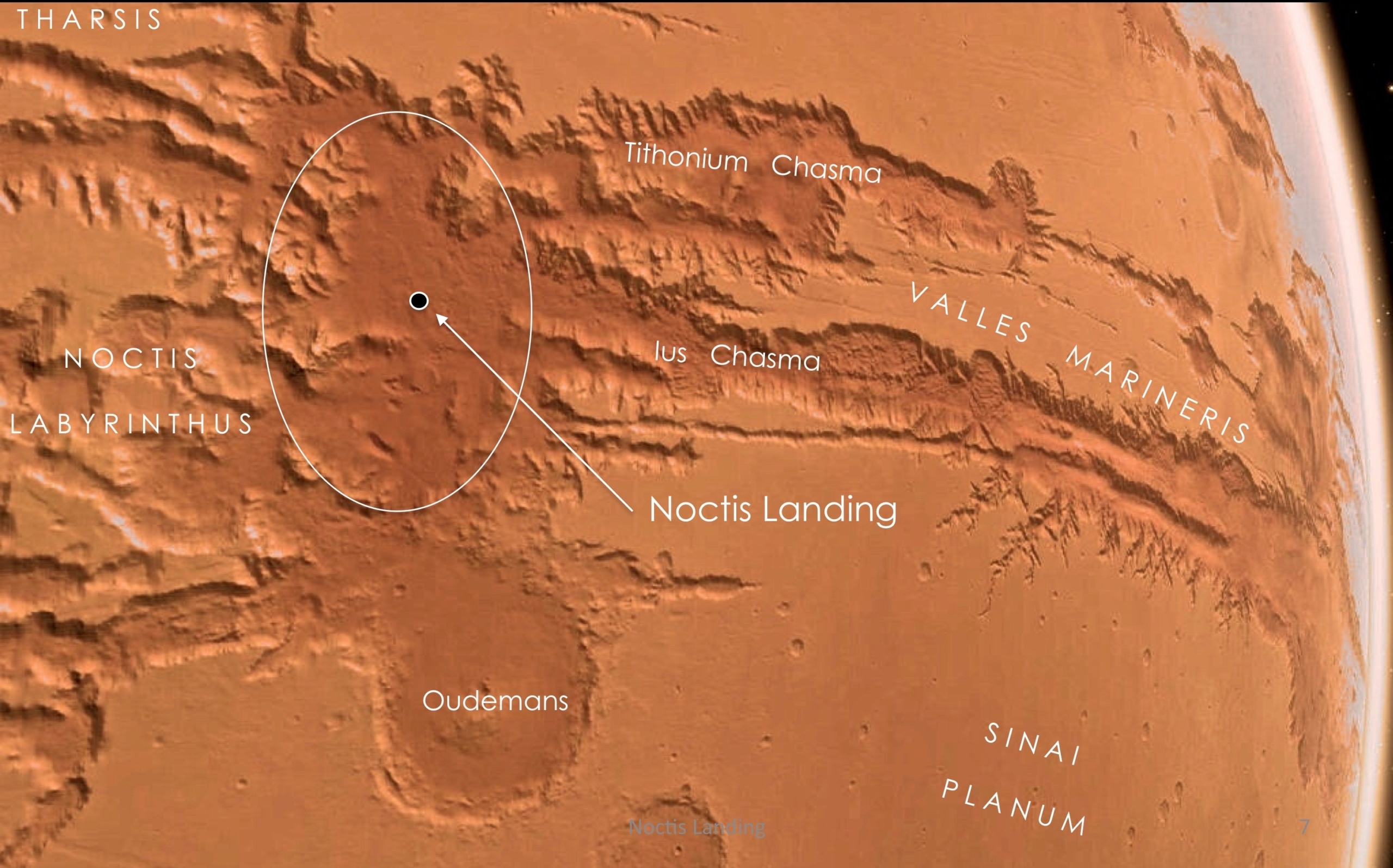

To top it off, the Mars relict glacier is near Noctis Landing, a site that Lee and colleagues have been proposing as a first-rate place for humans to land, establish a base and explore. That site offers the shortest possible surface excursions to the Martian volcanic plateau of Tharsis as well as Valles Marineris — the enormous canyon region on the Red Planet that exposes the longest record of Mars’ geology and evolution through time.

“Actually, while exploring the surroundings of Noctis Landing, we stumbled upon our Mars relict glacier,” Lee said. “So, you can imagine how excited that got us.”

Follow us @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab), or on Facebook (opens in new tab) and Instagram (opens in new tab).