Eugene Parker, the pioneering astrophysicist whose name graces NASA’s Parker Solar Probe mission, died Tuesday (March 15) at age 94.

Parker’s work focused on understanding the sun. In a key contribution to the field, he proposed that the sun produces a phenomenon called solar wind, a steady stream of charged particles that flows off the sun and across the solar system. The mission named for him seeks to understand the origins of the solar wind within the sun. Both NASA and the University of Chicago, where Parker had worked for decades, announced his death.

“We were saddened to learn the news that one of the great scientific minds and leaders of our time has passed,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in an agency statement.

“Dr. Eugene Parker’s contributions to science and to understanding how our universe works touches so much of what we do here at NASA,” he added. “Dr. Parker’s legacy will live on, through the many active and future NASA missions that build upon his work.”

Related: What’s inside the sun? A star tour from the inside out

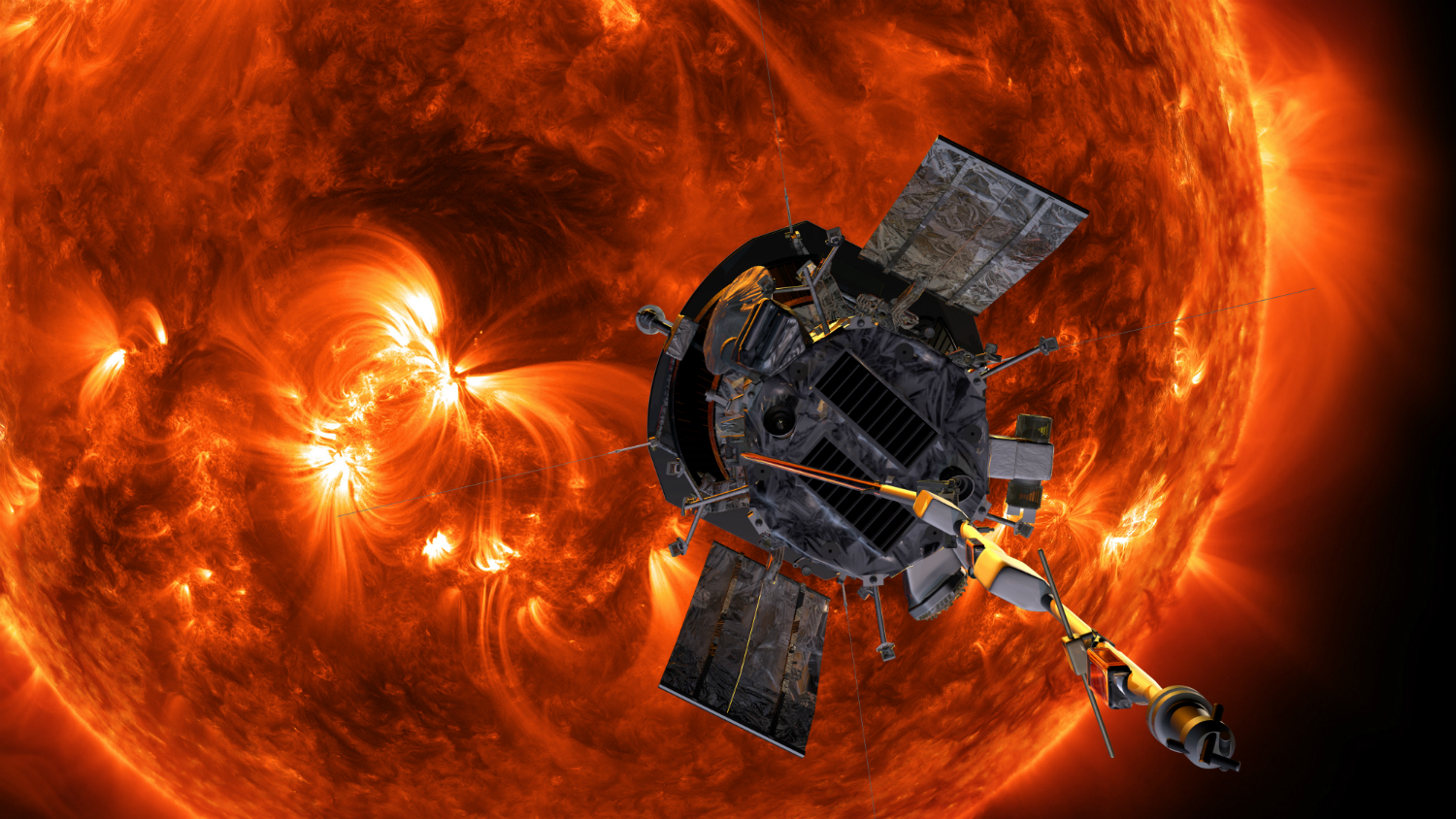

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe launched in August 2018 to study the sun’s outer atmosphere, called the corona, by diving within 4 million miles (6.5 million kilometers) of the visible surface of the sun. The spacecraft uses four instrument suites to study the superheated corona in an attempt to understand where the solar wind originates. The mission is expected to continue observations until 2025.

The mission, originally dubbed Solar Probe+, was named for Parker in 2017, making him the first living scientist to see a spacecraft named in his honor. Parker himself attended the launch, his first ever.

“Anyone who knew Dr. Parker, knew that he was a visionary,” Nicola Fox, director of NASA’s heliophysics division, said in the agency statement. “I was honored to stand with him at the launch of Parker Solar Probe and have loved getting to share with him all the exciting science results, seeing his face light up with every new image and data plot I showed him. I will sincerely miss his excitement and love for Parker Solar Probe. Even though Dr. Parker is no longer with us, his discoveries and legacy will live forever.”

Parker was born in 1927 in Houghton, Michigan, and completed an undergraduate degree in physics from Michigan State University in 1948 and a Ph.D. at the California Institute of Technology in 1951. He first worked as an instructor and assistant professor at the University of Utah.

In 1955, Parker joined the University of Chicago, where he contributed to astrophysics for another 67 years, according to the university’s statement. Two years after his appointment, he realized the superheated corona of the sun should, in theory, create charged particles leaving the sun’s surface at high speed.

Other scientists didn’t believe him, Parker recalled in 2018. “The first reviewer on the paper said, ‘Well I would suggest that Parker go to the library and read up on the subject before he tries to write a paper about it, because this is utter nonsense.'”

Support at last came from a colleague of Parker’s at the university, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar — who himself, decades later became the namesake of NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

While the future Nobel Prize winner wasn’t a fan of the particle idea, Chandrasekhar accepted Parker’s paper because he could not find problems with Parker’s mathematics, the University of Chicago said.

It only took a few more years before Parker’s proof came through. In 1962, NASA’s Mariner 2 spacecraft (the agency’s first interplanetary mission) discovered the solar wind during its voyage to Venus.

In the following decades, Parker expanded his research to examine cosmic rays, galactic magnetic fields, and other topics in astrophysics. As a result of his broad interests, a range of scientific concepts are named for him.

“His name is littered across astrophysics: the Parker instability, which describes magnetic fields in galaxies; the Parker equation, which describes particles moving through plasmas; the Sweet-Parker model of magnetic fields in plasmas; and the Parker limit on the flux of magnetic monopoles,” the university wrote of Parker.

Parker was also chair twice over for both the university’s astronomy and astrophysics department, as well as the astronomy section of the National Academy of Sciences. He retired in 1995, but remained active in the field of astrophysics until shortly before his death.

“Gene represented to me the ideal physicist — brilliant and accomplished, personable, articulate, but also humble,” Robert Rosner, an astrophysicist at the University of Chicago and a longtime colleague of Parker’s, said in the university statement.

“I will never forget the pleasure he took in exploring a science problem, and his terrific physical insights which were then buttressed by his analytical skills,” Rosner added. “And one can never forget the encouragement he gave to everyone he interacted with — his own students and postdocs, and his colleagues. His passing indeed marks a great loss for us all.”

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.