NASA is considering sending “hyper-specialized” scientists to the International Space Station to work alongside career astronauts.

The idea is by no means new, as NASA used to fly payload specialists assigned to specific space shuttle experiments in the early 1980s, notably including three-time spaceflyer Charlie Walker on behalf of his employer, McDonnell Douglas. Payload specialist requirements were changed, however, when the Challenger launch disaster of 1986 killed seven crew members and shifted NASA safety protocols.

NASA is now revisiting those protocols. The agency plans to seek funding in fiscal year 2023, which begins in October, for a new program that would send scientists to the International Space Station alongside astronauts, according to a SpaceNews report (opens in new tab) citing a July 13 presentation to a National Academies committee strategizing future biological and physical sciences research in space.

“We seek to bring scientists back into space,” Craig Kundrot, director of NASA’s biological and physical sciences division, said during the committee meeting.

Related: International Space Station, a photo tour

The committee met to plan a decadal survey that outlines community priorities that would direct future research. Simultaneously, NASA is working to commercialize space station research — including steps to carefully bring more non-career astronauts into the complex.

The space landscape has changed considerably since 1986 and NASA is already opening the International Space Station to non-career astronauts. Axiom Space successfully flew three individuals with no direct space experience in 2022 on its debut mission, Ax-1, commanded by former NASA astronaut Michael López-Alegría.

NASA is also taking steps to open up commercialization of the space station more generally, including funding early-stage private space stations in 2021 and accepting forthcoming commercial ISS modules from Axiom. A commercial airlock was added to the space station in 2020, too, to expand years of U.S. National Laboratory commercial research managed by the non-profit Nanoracks.

Kundrot alluded to this growing commercial participation in his National Academies presentation. “We are envisioning a different version of that now that we have, in this evolving, emerging commercial world, the private astronaut mission capability,” he said. “We seek to use that to fly hyper-specialized scientists to do research in LEO [low Earth orbit] that is really very hard for even the most closely trained astronaut in that field to do.”

Assuming that funding for the initiative will be approved in NASA’s budget, the agency will proceed with two requests for information (RFIs) to companies. The first will ask what research the companies would like to perform in low Earth orbit, while the second will discuss how scientists specifically would be able to contribute.

NASA’s private astronaut mission (PAM) protocols currently allow for two such missions a year for up to 30 days each. Axiom Space has been approved for three further PAMs through at least Ax-4. Ax-2 will launch between fall 2022 and spring 2023, while Ax-3 and Ax-4 have yet to be approved or scheduled. They will launch no earlier than 2023 once approved.

After PAM spaceflyers arrive in orbit, a portion of their research would gradually be handed off to NASA astronauts before the private mission concludes, according to Kundrot. One possibility, he said in the presentation, would be a “buddy system” in which an astronaut works alongside the PAM participant at the ISS, to learn how to do the science in microgravity once the scientist departs.

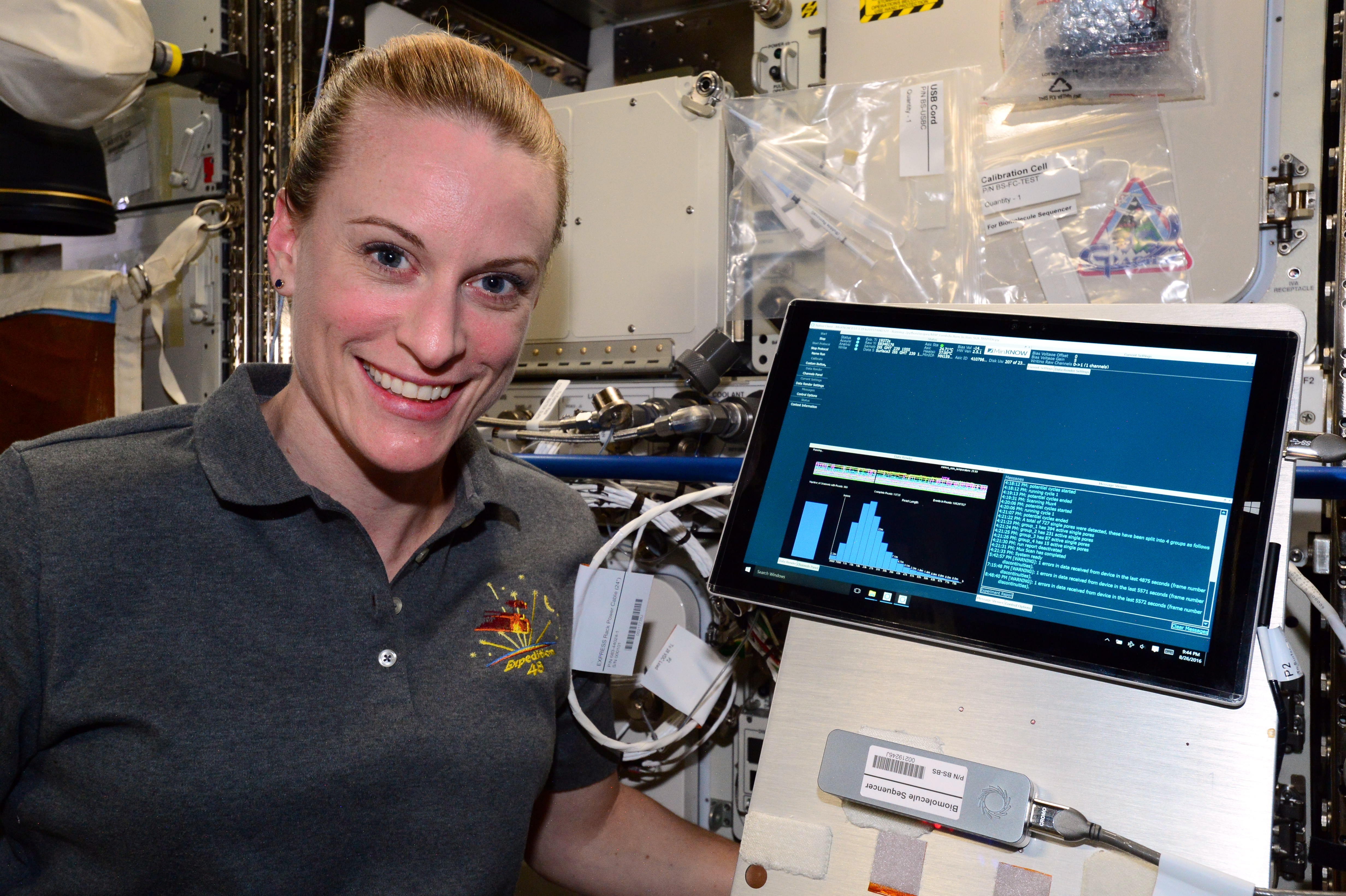

To be sure, NASA astronauts have already done complex research in space, including sequencing and repairing DNA. That said, Kumbrot said the “cutting edge” of research necessarily has “very few people” who are familiar enough with the systems and techniques required for some experiments.

As NASA continues to work towards conducting more science aboard the ISS, Kumbrot predicted some disciplines could experience 10-fold to 100-fold increases in research speed. He said that is because scientists on the ground would not need to wait months for shipments of materials to Earth, which is sometimes required to conclude experiments successfully.

If the funding and proposed schedule hold, Kundrot said the agency plans to request less than $10 million in fiscal year 2023 and grow that to $25 million by 2028. Missions would start in 2026. The Commercially Enabled Rapid Space Science (CERISS) initiative, however, has not been mentioned to date in NASA budget materials (opens in new tab).

The 2023 money would be allocated from a requested budget increase for biological and physical sciences at NASA, SpaceNews reports. NASA is requesting $100.4 million for this research in 2023, a 22% increase over its $82.5 million fiscal year 2022 allocation.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or Facebook (opens in new tab).