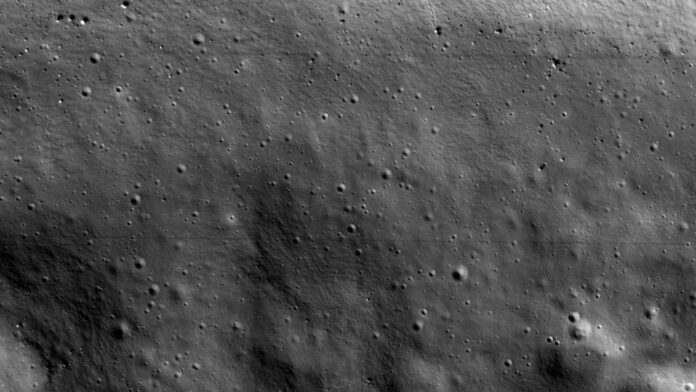

South Korea’s first moon mission has delivered a stunning first image from a camera designed to peer into permanently shadowed areas near the lunar poles.

The NASA-funded ShadowCam is designed to reveal regions where the sun never shines on the moon to assist future exploration efforts and has now demonstrated an unprecedented insight into Shackleton crater at the moon’s south pole.

ShadowCam is operating aboard Danuri, also known as the Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter (KPLO). It is one of six science payloads aboard Danuri, which launched back in August 2022 and arrived in lunar orbit in mid-December. The Korea Aerospace Research Institute (KARI) has already released Danuri’s first images from lunar orbit, and now ShadowCam is showing off its capabilities with an incredible test image of a permanently shadowed region in Shackleton crater.

Related: South Korea’s moon mission snaps stunning Earth pics after successful lunar arrival

The top fifth of the image shows the base of the steep wall of Shackleton crater, with the lower portions displaying the crater floor. At the top, the track of a roughly 16 feet (5 meters) diameter boulder that rolled down the wall of the crater can be seen.

“ShadowCam reveals the interior but none of the rim because the detector is so sensitive that it saturates whenever viewing terrain directly illuminated by sunlight,” Mark Robinson of Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration said in the statement.

ShadowCam builds on the cameras aboard NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter which has been operating since 2009, but provides unprecedented views into permanently shadowed regions, or PSRs.

The moon, unlike the Earth, only has a slight axial tilt, meaning some areas never receive direct sunlight. ShadowCam’s high sensitivity means it can detect light dimly reflected from nearby features and provide never before seen views into perpetually dark areas.

The camera will be used to image the moon’s permanently shadowed regions with a resolution of better than 6.6 feet (2 meters) per pixel and will provide mapping for use by future surface missions such as NASA’s VIPER to search for volatiles, elements or substances with low boiling points such as water, hydrogen or helium.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).