Nearly 50 years after Apollo 17 astronauts collected rocks from the lunar surface, NASA is finally tapping their samples as it prepares for new missions to the moon.

NASA set aside the Apollo 17 moon rock samples to preserve the precious samples collected in 1972 by astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt (also a geologist) collected in the Taurus-Littrow Valley within Mare Serenitatis.

The agency knew that science advances in the coming decades would mean there would be techniques available to study the rocks that were not available to scientists of the 1970s. With NASA’s Artemis program hoping to send astronauts to the moon in 2025 (the date may be delayed to at least 2026), officials determined now would be a good time to examine a sample from Apollo 17, the last human mission on the moon to date.

“The agency knew science and technology would evolve and allow scientists to study the material in new ways to address new questions in the future,” Lori Glaze, NASA’s director of the planetary science division, said in an agency statement March 4.

Related: NASA’s Artemis 1 moon mission explained in photos

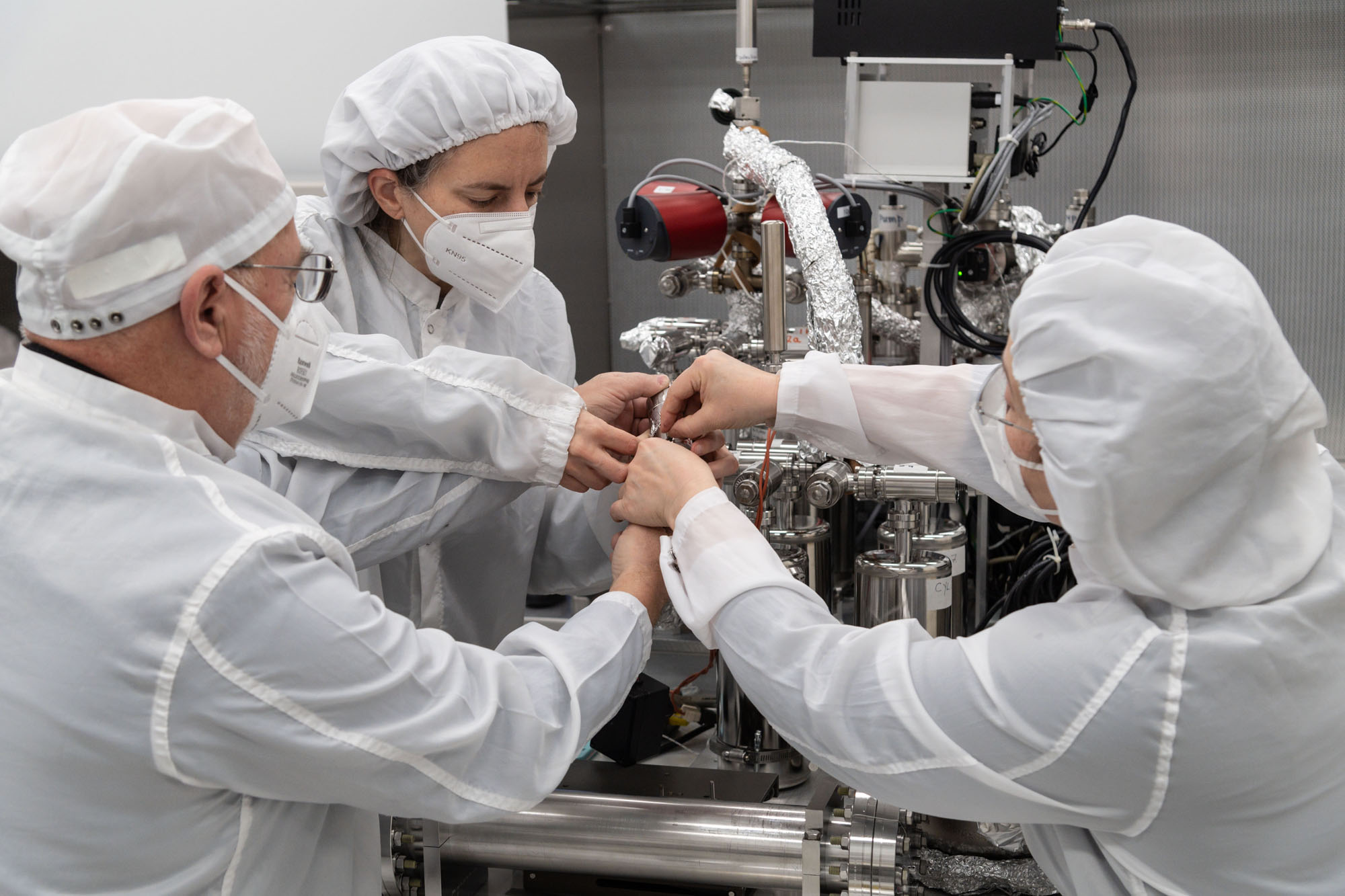

Scientists unsealed the sample, dubbed the Apollo Next Generation Sample Analysis Program (ANGSA) 73001, at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. The team is seeking to understand the lunar surface with modern-day science instruments to prepare for planned Artemis missions near the south pole of the moon.

Cernan and Schmitt collected the sample as part of a “drive tube.” They hammered a pair of connected, 14-inch (35-cm) tubes down, one atop the other, into the surface to pick up rocks and soils from a landslide.

One of the tubes (the bottom half) was sealed on the moon before bringing it back to Earth; there is only one other sample ever collected under these conditions, NASA said, making the collection process almost unique. The other tube (the top half) was returned in a normal and unsealed character.

This sealed tube, which is being opened now, was stored in an “outer vacuum tube” and then kept in an atmosphere-controlled environment at Johnson for half a century. (As for the other half of the segment, that was opened in 2019, showing “rocklets” or grains and smaller objects interesting for lunar geologists.)

The sealed part of the core happened to be on the lower segment, meaning that the temperature was quite cold when it was collected. In the 1970s, scientists didn’t know that volatiles (or substances, like water, that evaporate in room temperatures) were present on the surface in such low temperatures. Now that scientists know what to look for, they are going to hunt for these volatiles.

There won’t be much gas available, but modern mass spectrometry technology may be able to analyze what is there. The technique allows scientists to look at a mass of “unknown molecules” (or components of matter). The gas can also be portioned out for different researchers to examine in their respective facilities.

NASA’s Ryan Zeigler, Apollo sample curator, is overseeing the project, which was proposed a decade ago by the University of Mexico’s Chip Shearer. “A lot of people are getting excited,” Zeigler said about the work, which began Feb. 11 and will likely require months to extract the sample and its gas.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.