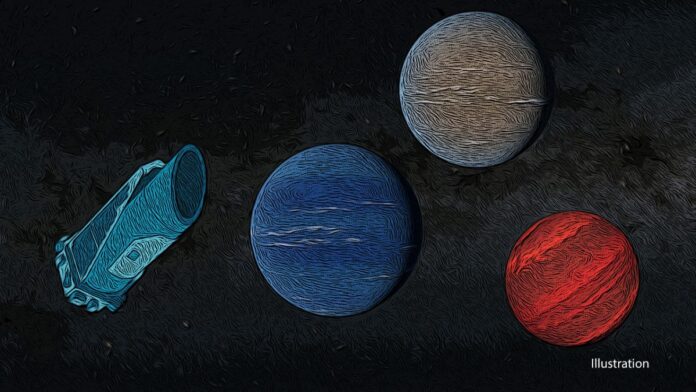

NASA’s prolific Kepler space telescope, which shut its powerful eye nearly five years ago, continued finding exoplanets even while taking its final breaths.

A team of astrophysicists and citizen astronomers combing through the last chunk of data that Kepler sent home say they found two new worlds and a “candidate” planet closely orbiting three faint stars about 400 light-years from Earth.

So far, these are the only exoplanets that have been discovered in the telescope’s final dataset, making them the very last worlds that Kepler glimpsed just before it ran out of fuel and was shut down in late 2018.

“These are fairly average planets in the grand scheme of Kepler observations,” Elyse Incha, a senior at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a lead author of the new study, said in a NASA statement. “But they’re exciting because Kepler observed them during its last few days of operations. It showcases just how good Kepler was at planet hunting, even at the end of its life.”

Related: The 10 most Earth-like exoplanets

The Kepler telescope launched in March 2009 to stare at 150,000 selected stars in the constellation Cygnus, on a primary mission expected to last 3.5 years. The spacecraft documented dips in starlight that hinted at orbiting planets — a technique known as the “transit method.”

Kepler’s first four years in space went smoothly. But two of its four reaction wheels — devices crucial to point the observatory at its targets — failed in 2013, and it was no longer able to focus on stars precisely.

A year later, scientists implemented a work-around solution that used the telescope’s two good reaction wheels and its onboard thrusters to maintain a slightly unstable but workable balance. Kepler fought on for four more years and gazed at different slices of the sky once every 80 days, on a new mission known as K2 during which it discovered hundreds more exoplanets.

By late August 2018, Kepler’s observation power had deteriorated so much that the month-long K2 Campaign 19 — Kepler’s final observation cycle — yielded only a week of high-quality data, the team wrote in the new study.

In that limited dataset, which included information about 33,000 additional stars, the team spotted one transit each for three exoplanets around three dim stars. Two of those planets orbit cool, red dwarf stars and are what astronomers call mini-Neptunes: K2-416 b, which is 2.6 times wider than Earth and orbits its star once every 13 Earth days; and K2-417 b, which is three times wider than Earth and circles its star every 6.5 days.

Both worlds are smaller than Neptune. They’re enveloped by hot, tenuous atmospheres and are likely uninhabitable, researchers say. The third candidate, which circles a sun-like star named EPIC 245978988, has not been confirmed yet.

To verify what they were seeing were really planets and not false positives because of, say, two closely orbiting stars, the team also pored over lower-quality data that Kepler had collected just over a week before being decommissioned.

“We tried to see what last information we could squeeze out of it,” study co-author Andrew Vanderburg, a physics professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, said in a different statement. “And we’re really pushing up against the last few days, the last few minutes, of observations Kepler collected.”

Related: RIP, Kepler: NASA’s revolutionary planet-hunting telescope runs out of fuel

In those final moments, the telescope’s thrusters were firing erratically, leading to sharp jumps in the collected “light curves,” researchers said. To validate the presence of K2-416 b and K2-417 b, the team looked for the planets’ second transit around their respective stars. They found that the stars’ light curves had dipped at the same depth and duration as they had during the first detected transit, confirming the candidates to be genuine exoplanets.

For both transit detections, a team of citizen astronomers visually inspected the light curves of all 33,000 stars rather than relying on automated techniques commonly used in the search for exoplanets, according to the study.

“People doing visual surveys — looking over the data by eye — can spot novel patterns in the light curves and find single objects that are hard for automated searches to detect. And even we can’t catch them all,” co-author Tom Jacobs, a team member of the Visual Survey Group, said in the NASA statement. “I have visually surveyed the complete K2 observations three times, and there are still discoveries waiting to be found.”

For further confirmation, the team scoured image archives from the past 70 years to rule out the possibility of any background stars leading to false positives. They found no such possible complications for K2-416 b and K2-417 b, further confirming their planet status. But the third, unconfirmed exoplanet may have a “faint-red companion” orbiting very close to the star that is currently difficult to resolve.

Researchers also used NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which was launched in 2018 with a similar goal as Kepler’s, to validate K2-417 b’s identity. TESS, which has mapped over 93% of the sky so far, recently celebrated five years in space.

“In many ways, Kepler passed the planet-hunting torch to TESS,” Knicole Colón, a TESS project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland who also worked on the Kepler mission but wasn’t involved in the new study, said in the NASA statement. “Kepler’s dataset continues to be a treasure trove for astronomers, and TESS helps give us new insights into its discoveries.”

Kepler was incredibly prolific throughout its long life. Its tally of confirmed exoplanets stands at more than 2,660, nearly half of all alien-planet discoveries to date.

This research was described in a paper published Tuesday (May 30) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Sharmila Kuthunur on Twitter @skuthunur. Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.