A new analysis of distant galaxies imaged by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) shows that they share characteristics with a rare class of galaxies called “green peas” found in our cosmic backyard.

One of these galaxies, which existed when the universe was just 5% of its current age, may be one of the most “chemically primitive” galaxies astronomers have ever seen.

“With detailed chemical fingerprints of these early galaxies, we see that they include what might be the most primitive galaxy identified so far,” research leader James Rhoads, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, said in a statement. “At the same time, we can connect these galaxies from the dawn of the universe to similar ones nearby, which we can study in much greater detail.”

Related: James Webb Space Telescope’s best images of all time (gallery)

Read more: Early James Webb Space Telescope findings take center stage at key astronomy conference

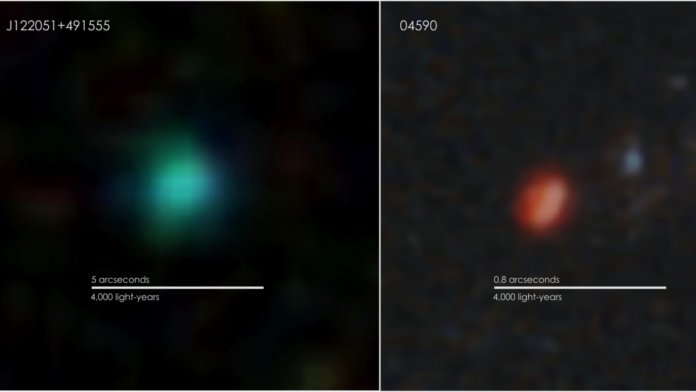

“Green pea” galaxies were discovered in observations from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey in 2009. Green peas are so named because they stand out as small, round, unresolved dots with a distinctly green shade. They appear green because a large fraction of light from these rare galaxies originates from bright, glowing gas clouds that emit light at specific wavelengths, rather than the broad spectrum of light and continuous colors emitted by stars in other galaxies.

These green pea galaxies are rare, accounting for just 0.1% of nearby galaxies. They are also compact (in cosmic terms), with diameters of just 5,000 light-years — just 5% the width of our galaxy, the Milky Way. But what green pea galaxies lack in size, they seem to make up for in rates of star birth.

“Peas may be small, but their star-formation activity is unusually intense for their size, so they produce bright ultraviolet light,” Keunho Kim, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cincinnati and a member of the analysis team, said in the statement. “Thanks to ultraviolet images of green peas from Hubble and ground-based research on early star-forming galaxies, it’s clear that they both share this property.”

Green peas in the early universe

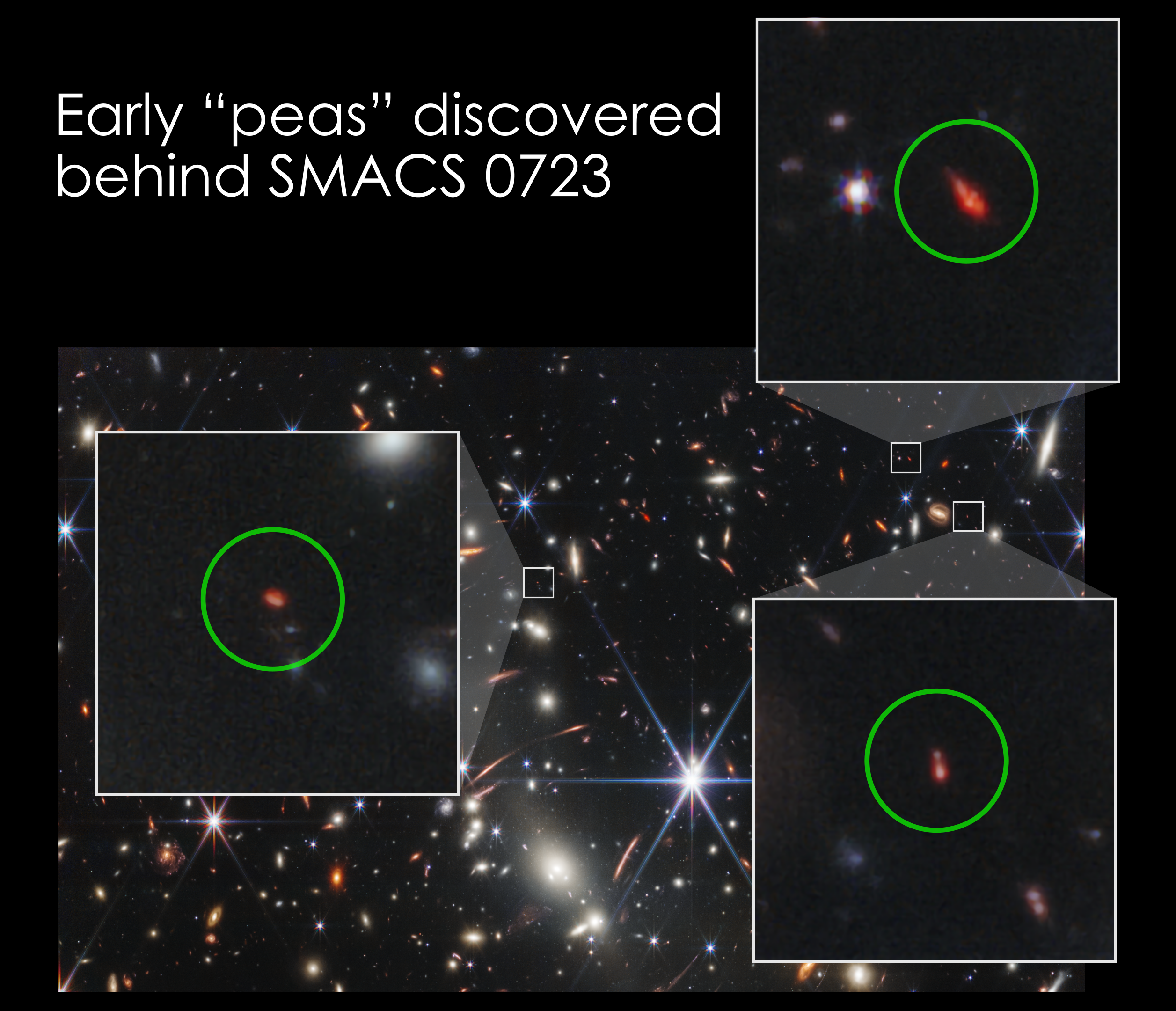

In July 2022, the JWST team revealed the deepest and sharpest infrared image of the distant universe ever taken, which captured the galaxies in and behind a galactic cluster known as SMACS 0723.

As a result of a phenomenon called gravitational lensing, SMACS 0723 is magnifying and distorting the appearance of the galaxies behind it. The image revealed a trio of infrared objects that resemble the distant relatives of local green pea galaxies.

The gravitational lensing effect of SMACS 0723 magnified the most distant of these galaxies by a factor of 10, giving the space telescope a massive natural observing boost.

Using its Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) instrument, the JWST also obtained the spectra of the galaxies in the image, which revealed the telltale signs of oxygen, hydrogen and neon emissions, further strengthening the resemblance to green pea galaxies.

These spectrographic data allowed the team to measure the amount of oxygen in these distant and early galaxies for the first time, revealing that two of these galaxies have around 20% the oxygen as the Milky Way contains.

As stars die, they enrich the universe with heavy elements that they forged during their lifetimes, meaning early galaxies like these should be relatively deficient in elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, which astronomers refer to as “metals,” compared with older galaxies like our own.

“We’re seeing these objects as they existed up to 13.1 billion years ago, when the universe was about 5% its current age,” Sangeeta Malhotra, a researcher at NASA Goddard and a member of the research team, said in the statement. “And we see that they are young galaxies in every sense — full of young stars and glowing gas that contains few chemical products recycled from earlier stars.”

The third of these early lensed galaxies is more unusual, however. “One of them contains just 2% the oxygen of a galaxy like our own and might be the most chemically primitive galaxy yet identified,” Malhotra said.

The team’s research was published Jan. 3 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and was presented at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle on Jan. 9.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.