New research points to increasing pollution in the upper atmosphere due to reentering satellites, rocket bodies and other incoming spaceflight flotsam.

That troublesome trend is leading researchers to come up with mitigation proposals, one of which would use fabrication concepts to reduce the size of space debris pieces that make it to Earth.

The Aerospace Corporation, a California-based nonprofit company, has established a Space Safety Institute (SSI). One of SSI’s five focus areas is launch and reentry safety, and “Design for Demise” is an item the institute is paying attention to.

Related: Kessler Syndrome and the space debris problem

“The goal for Design-for-Demise concepts is to use materials and design concepts in the construction of space hardware so that the hardware will demise in a controllable fashion during reentry,” said William Ailor of The Aerospace Corporation. “Ideally, the hardware would be reduced to a cloud of very small particles that would not be harmful to people on the ground or to an aircraft.”

Ailor said that analysis of debris recovered after reentries show that certain low-melting-point materials such as aluminum will, unless shielded by other materials, totally demise if exposed to reentry heating. So, use of these materials for external and core structures will help assure that interior components will be released quickly and exposed to a high heating environment.

“Components made of higher melting point materials such as stainless steel and titanium will survive intense heating and have been recovered on the ground,” Ailor added. “Designs that expose high-melting-point materials to high temperatures directly for long periods will help.”

That said, Ailor explained that the best solution to minimize hazards is to purposefully de-orbit space hardware into “safe” regions where there are no people and aircraft at the time of reentry.

Space hardware fallout

On the other hand, there’s the feel-good observation that 75% of the Earth is covered by ocean waters. Consequently, most surviving space clutter merely tumbles harmlessly into watery graves. But there are incidents of space hardware fallout making it to terra firma.

A recent report in Nature Astronomy called “Unnecessary risks created by uncontrolled rocket reentries (opens in new tab)” analyzed three decades of data to produce a “casualty expectation” — the risk to human life from the uncontrolled reentry of rocket bodies into Earth’s atmosphere.

Michael Byers of the University of British Columbia and his colleagues explain that, under current practices, there is a roughly 10% chance that one or more casualties will occur over the next decade from falling rocket debris. Furthermore, without multilateral agreements for mandated controlled rocket body reentries, launcher nations will export these risks pointlessly, creating danger for people on the surface.

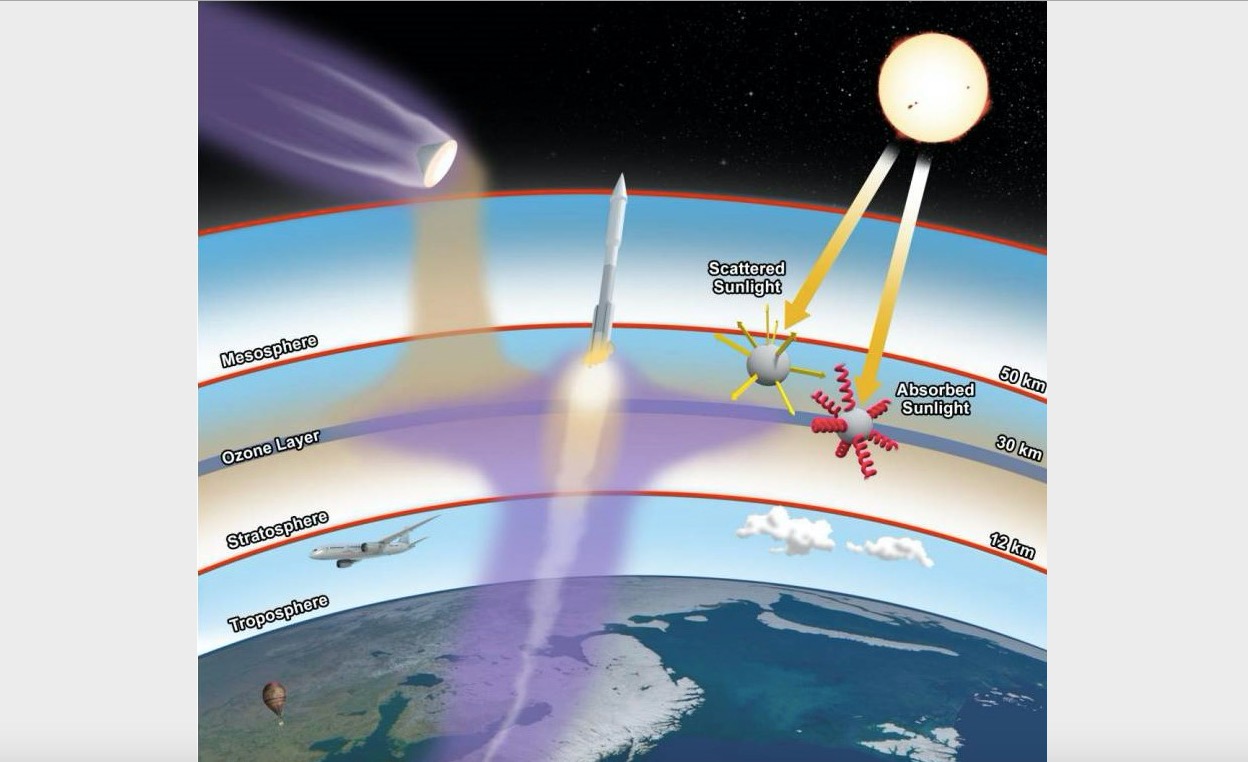

In another recent study (opens in new tab), published in the journal Earth’s Future, researchers from University College London (UCL), the University of Cambridge and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology assessed the impact of rocket launches and space debris on stratospheric ozone and global climate.

Eloise Marais, a study co-author, is an associate professor of physical geography at UCL. She told Space.com that, even if a reentering rocket were to completely burn up, it would produce the air pollutant nitric oxide (NOx) from the high temperatures.

“NOx contributes to depletion of ozone in the stratosphere, where ozone protects us from harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun. There are also likely other pollutants formed from combustion of the rocket material, such as alumina (Al2O3) that also depletes ozone and at a faster rate than NOx,” Marais said. “In essence, we need more sustainable solutions for dealing with space debris.”

Related: The biggest spacecraft to fall uncontrolled from space

Chinese version of Russian roulette

Several wearisome cases in point involve China’s Long March 5B rocket, which most recently launched the Wentian lab module to the Tiangong space station, which is still under construction.

After Long March 5B launches, the rocket’s core stage reaches orbit and then plays a Chinese version of Russian roulette, zooming around Earth for a week or so before finally falling uncontrolled to Earth.

That’s a departure from pretty much every other orbital rocket, whose first stages ditch into the ocean or over unpopulated land before reaching orbit — or, in the case of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets, land vertically for future reuse.

“It seems that the Chinese have entered ‘defense mode,’ basically repeatedly saying that the reentry performed by the Long March 5B core stage ‘was common practice in the space industry’ with little casualty risks,” said aerospace engineer Jean Deville, a close observer of China’s space program who co-produces the website Dongfang Hour.

“We don’t know why a safer de-orbiting method wasn’t considered during the design phase,” Deville told Space.com. “Was the risk considered truly acceptable? Or was there a technical or a development timeline limitation at the time?”

Deville notes that Zhao Lijian, China’s foreign ministry spokesperson, has stated that the Long March 5B “adopted a specific technical design, making most components burn up during reentry.”

“While we’re lacking specifics,” Deville said, “could this be hinting at some effort during the design process to make sure that most of the materials used would burn up during reentry?”

Whatever the case, Deville said there are several more Long March 5B launches coming up. In October, for example, China plans to launch the Mengtian lab module to meet up with Tiangong, wrapping up the station’s assembly phase. Also, in early 2024, another Long March 5B will hurl into space the large Xuntian space telescope, Deville said.

That booster class could possibly launch a couple more times at the end of the decade, Deville said, as several high-ranking space program leaders have suggested a possible expansion of Tiangong.

“Lots of open questions, for which I don’t have answers,” Deville concluded.

Leonard David is author of the book “Moon Rush: The New Space Race,” published by National Geographic in May 2019. A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).