The icy Saturn moon Mimas may be a “stealth” ocean world, according to new research.

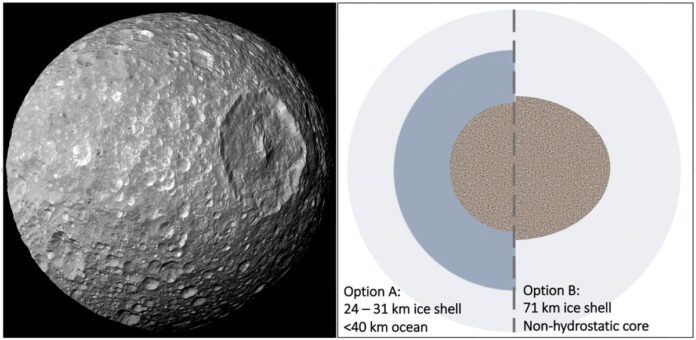

Mimas, the smallest and innermost of Saturn‘s major moons, is believed to generate the right amount of heat to support a subsurface ocean of liquid water. And recent simulations of the moon’s Herschel impact basin — the most striking feature on its heavily cratered surface — along with the lack of tectonics on Mimas, support the existence of a geologically young internal ocean surrounded by a thinning ice shell, according to a statement (opens in new tab) from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in San Antonio, Texas.

“In the waning days of NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn, the spacecraft identified a curious libration, or oscillation, in Mimas’ rotation, which often points to a geologically active body able to support an internal ocean,” Alyssa Rhoden, co-author of the new study and a scientist at SwRI, said in the statement.

Related: 10 extraordinary ocean worlds in our solar system (photos)

However, despite this wobble, the heavily cratered surface of Mimas led scientists to initially consider the moon a frozen block of ice. That’s because most ocean worlds — such as the geyser-spouting Enceladus, one of Saturn’s other moons — tend to be fractured and show other signs of geologic activity. Mimas, however, lacks any telltale tectonic traits.

“Mimas seemed like an unlikely candidate, with its icy, heavily cratered surface marked by one giant impact crater that makes the small moon look much like the Death Star from ‘Star Wars,'” Rhoden said in the statement. “If Mimas has an ocean, it represents a new class of small, ‘stealth’ ocean worlds with surfaces that do not betray the ocean’s existence.”

When modeling the formation of the Hershel impact basin, scientists found that Mimas’ ice shell had to be at least 34 miles (55 kilometers) thick at the time of the impact. Meanwhile, observations of Mimas and models of its internal heating suggest that its current ice shell is less than 19 miles (30 km) thick, according to the statement.

These measurements suggest that an internal ocean has been warming and expanding since the basin formed. What’s more, the researchers were only able to recreate the shape of the basin when factoring an interior ocean into their models.

“We found that Herschel could not have formed in an ice shell at the present-day thickness without obliterating the ice shell at the impact site,” Adeene Denton, lead author of the study and a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Arizona, said in the statement. “If Mimas has an ocean today, the ice shell has been thinning since the formation of Herschel, which could also explain the lack of fractures on Mimas. If Mimas is an emerging ocean world, that places important constraints on the formation, evolution and habitability of all of the mid-sized moons of Saturn.”

These new models challenge scientists’ current understanding of thermal-orbital evolution, Rhoden said in the statement.

“Evaluating Mimas’ status as an ocean moon would benchmark models of its formation and evolution,” Rhoden said. “This would help us better understand Saturn’s rings and mid-sized moons as well as the prevalence of potentially habitable ocean moons, particularly at Uranus. Mimas is a compelling target for continued investigation.”

Their findings were published on Dec. 26, 2022 (opens in new tab), in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).