Growing up in the Bronx during the 1960s and ’70s, one of my mentors in astronomy was Dr. Kenneth L. Franklin, Chairman and chief scientist at New York’s Hayden Planetarium, who wrote about celestial events for the World Almanac and The New York Times.

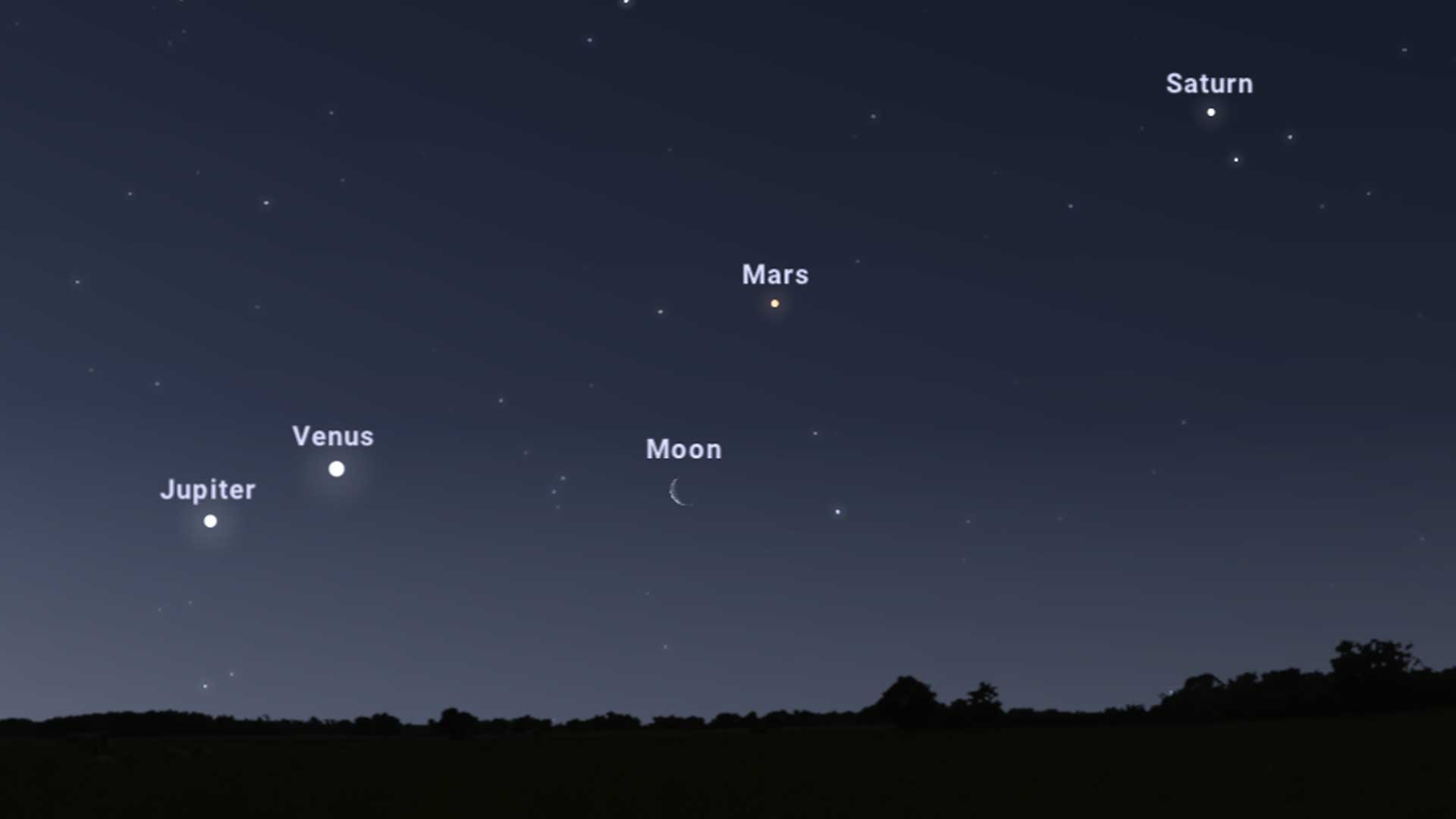

Periodically Ken would make reference to our “dynamic and ever-changing sky.” Such an eloquent description would certainly fit the day-to-day changes among the planets in our early morning sky this month. Morning planets are front and center in April, with four out of the five brightest solar system planets, lined up across the east-southeast sky.

If you need some gear to see April’s predawn planets, check out guides for the best telescopes and best binoculars to find the right instrument for you for the next skywatching event. If you’re hoping to snap photos of the planets, here are our guides for the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

The first week of April

The month starts off with three bright planets clustered low in our east-southeast sky just before sunrise. Venus, Saturn and Mars are within six degrees of separation, but each morning thereafter the configuration noticeably changes. Mars and Saturn approach each other more closely than the apparent diameter of the moon on April 5.

Then, beginning on April 8, Jupiter, still buried deep in the dawn as the month begins, makes its presence felt, albeit far below and to the left of the other three planets. By the morning of April 19, all four planets will be stretched out in a diagonal line spanning just over 30 degrees; from lower left to upper right: Jupiter, Venus, Mars and Saturn.

The moon joins in too

The main event comes during the final week of April with the approach of magnitude -2 Jupiter to magnitude -4 Venus, seven times brighter. Meanwhile, the crescent moon looms, passing below Saturn on April 25, Mars on April 26 and finally Jupiter and Venus on April 27. Make sure you have a wide-open view of the east-southeast horizon that morning with no obstructions and set your alarm clock for 5:15 a.m.

In a single glance, you’ll see the three brightest objects in the night sky: a 12% illuminated crescent moon, Jupiter 4 degrees to its upper left and Venus hovering 5 degrees directly above the lunar sliver. Venus and Jupiter are separated by 3.2 degrees that morning, 2 degrees on April 28, and 1.3 degrees on the April 29.

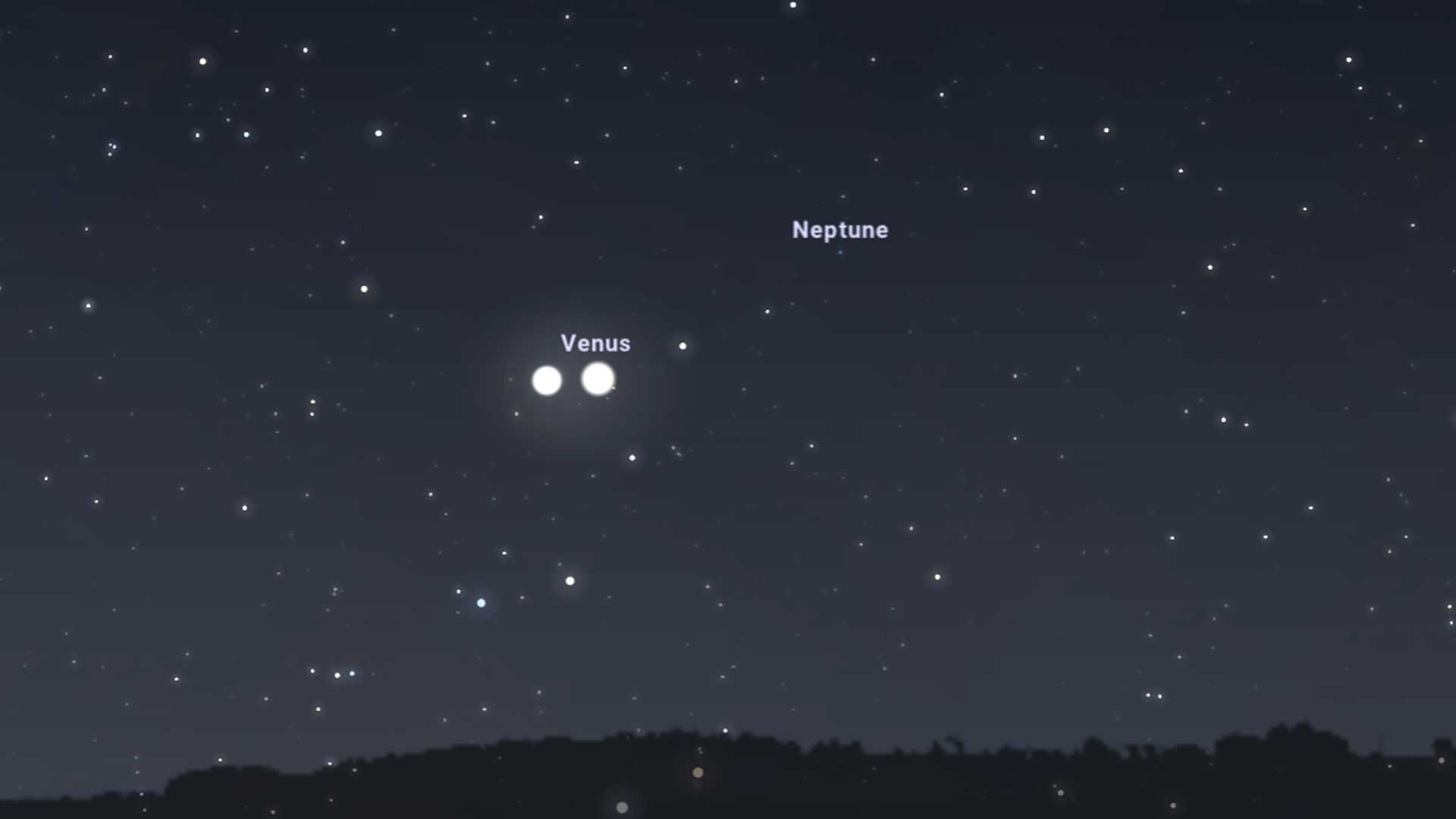

On April 30, Venus and Jupiter stand side-by-side, separated by 0.45 degrees for North America and visible together in a telescope’s low-to-medium power view. Jupiter will appear round, three of its four Galilean satellites will be visible and Venus will look slightly more than half-lit.

The Far East sees them near their moments of conjunction and appulse (closest approach) when Venus passes just 0.25 degrees north of Jupiter. This is the closest Venus-Jupiter conjunction since August 2016, when they were deeper in the glow of the sun. A similarly striking pairing of these two planets will occur in the evening sky on March 1, 2023.

Breaking up is hard to do

The denouement following April 30 is swift. On May 1, the two planets are still strikingly close, separated by 0.6 degrees and this will increase by almost a degree per day, so that by May 8, Jupiter shines 7.1 degrees to Venus’ upper right.

In the months to come, these two brightest planets will go in very different ways. Venus will continue to hug the edge of dawn low in the east until August, then will slowly sink into the sunrise. By that time Jupiter will be on the other side of the sky, dominating the evening views.

Planet peregrinations

All of the naked-eye planets, and the moon as well, closely follow an imaginary line in the sky called the ecliptic. The ecliptic is also the apparent path that the sun appears to take through the sky as a result of the Earth’s revolution around it.

Technically, the ecliptic represents the extension or projection of the plane of the Earth’s orbit out towards the sky. But since the moon and planets move in orbits, whose planes do not differ greatly from that of the Earth’s orbit, these bodies, when visible in our sky, always stay relatively close to the ecliptic line.

Twelve of the constellations through which the ecliptic passes form the zodiac; their names which can be readily identified on standard star charts are familiar to millions of horoscope users who would be hard-pressed to find them in the actual sky.

Ancient man probably took note of the fact that the planets — themselves resembling bright stars — had the freedom to wander in the heavens, while the other ‘fixed’ stars remained rooted in their positions. This ability to move seemed to have an almost magical, God-like quality. And evidence that the planets came to be associated with the gods, lies in their very names, which represent ancient deities.

The skywatchers of thousands of years ago must have deduced that if the movements of the planets had any significance at all, it must be to inform those who could read celestial signs of what the fates held in store. Indeed, even to this day, there are those who firmly believe that the changing positions of the sun, moon and planets can have a decided effect on the destinies of individuals and nations on Earth.

The only problem with this theory is that the planets in the night sky are always shifting in and out of celestial liaisons. Astronomical amnesia allows us to forget the last time we saw them assembling for such a performance.

And we also usually fail to recall that none of the influential magical thinking attributed to the previous event ever materialized.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.