Solar sailing can be a relatively slow-motion affair, but progress in the nascent field is quickly gaining steam.

The idea is not to use conventional “gas guzzling” propulsion but rather to employ ever-present and energetic solar photons to travel through space. Over time, this steady thrust from sunlight can accelerate a spacecraft to very high speeds.

Harnessing this technology, which is now being pursued by multiple nations, could allow probes to efficiently explore the outer solar system and even interstellar space, advocates say.

But the technology has been a work in progress for many years — and it hasn’t always been smooth sailing.

Related: What is a solar sail?

Troubled tech demo

NASA’s Artemis 1 moon mission, which launched in November 2022, sent the agency’s Orion capsule on an uncrewed shakeout cruise to lunar orbit and back. But Artemis 1 also lofted 10 tiny ridealong cubesats, one of which was a solar sailer — NASA’s Near-Earth Asteroid (NEA) Scout.

NEA Scout was developed under NASA’s Advanced Exploration Systems division. The cubesat was designed and developed by two NASA centers, the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

NEA Scout carries an ultra-thin sail that, when fully deployed via long booms, covers 925 square feet (86 square meters). That’s fairly small for a solar sail, but it should be big enough for the cubesat cruise through deep space, showing that the propulsion technology is ready for prime time — one of the mission’s chief goals.

“I emphasize that NEA Scout is a technology demonstration and also a science mission,” the mission’s principal investigator, Les Johnson of NASA Marshall, told Space.com.

NEA Scout aims to sail to a small asteroid named 2020 GE and study it up close. The cubesat deployed as planned shortly after Artemis 1’s Nov. 16 liftoff, but it soon ran into trouble: The mission team has so far been unable to communicate with NEA Scout.

“We are not yet in contact with the spacecraft, though we are using the Deep Space Network every day trying,” Johnson, who has been working on the mission for nearly a decade, told Space.com. “We still have hope and are still trying!”

Related: The 10 greatest images from NASA’s Artemis 1 moon mission

Mega-sail

Johnson has been spearheading solar sail work for 20 years, off and on, given the ebb and flow of development dollars.

The technology has “come a long way, and we’re working on the next one, Solar Cruiser,” said Johnson.

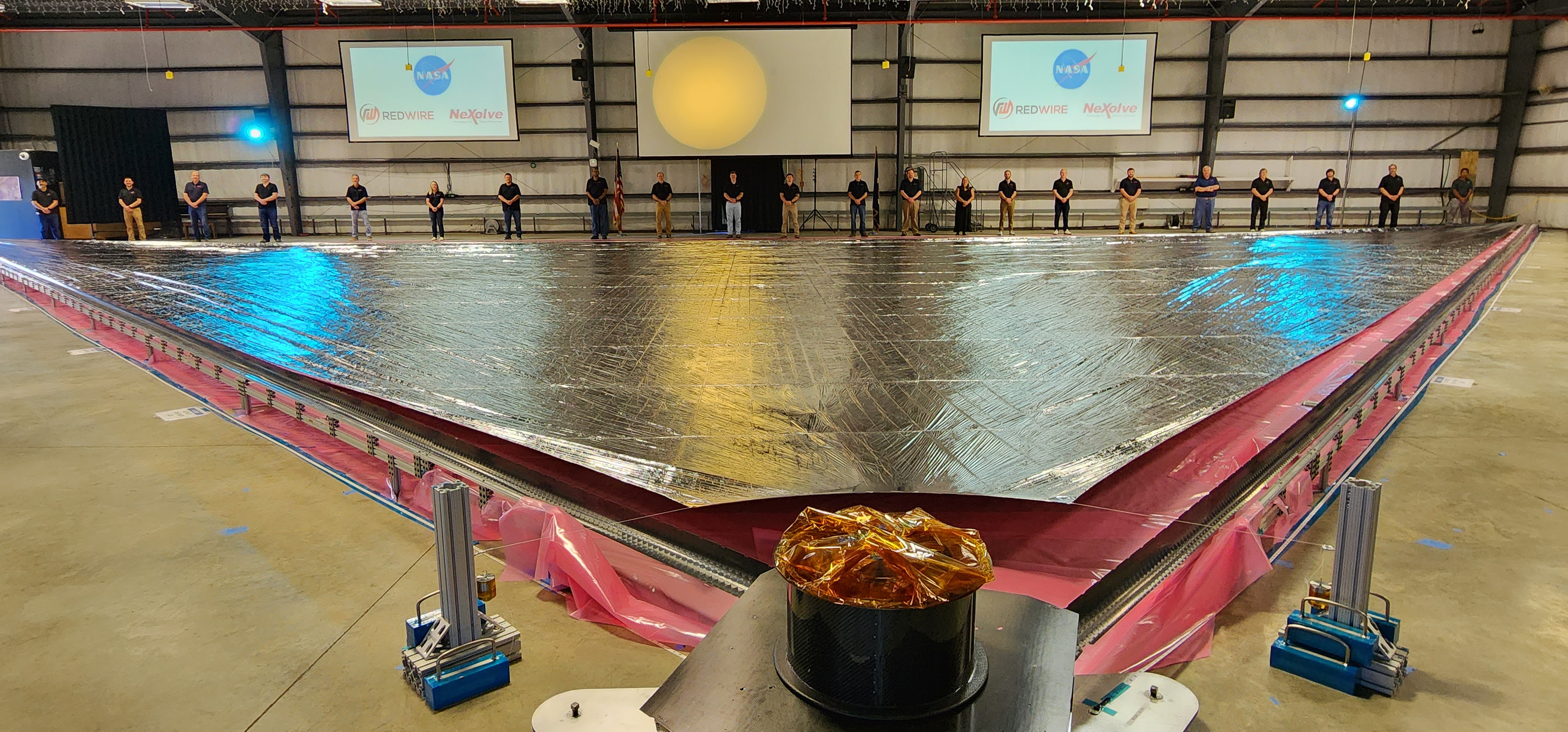

Solar Cruiser’s sail is a whopping 17,800 square feet (1,650 square meters) in size — large enough to cover more than six tennis courts. Solar Cruiser has completed a preliminary design review, and the project is eying a flight opportunity for later in this decade.

A recent unfurling of one quadrant (a test article) of Solar Cruiser’s huge sail took place at Marshall, spotlighting the evolution of the mega-sail design.

Solar Cruiser, which is sponsored by the Solar Terrestrial Probes Program in NASA’s Heliophysics Division, could lay the foundation for future sailing missions that improve space weather monitoring and prediction and help answer questions about the sun, its interaction with Earth and other elements of the heliosphere.

Big changes have occurred over Johnson’s two decades of solar sail work, due in large part, he said, to the smartphone revolution: Commercial micro-technology has spilled over into spacecraft, making them lighter weight. “The miniaturization of spacecraft suddenly makes solar sails more viable,” Johnson said.

Leslie McNutt, NASA’s deputy project manager for Solar Cruiser, voiced similar sentiments, saying that solar sailing has evolved in the past 20 years from idea to reality. NASA and industry partners are engineering innovative sail technologies to help push the limits of what small satellites can do in space and how far they can go, she told Space.com.

“One of the toughest challenges with solar sails is deploying them in space. You know how your tape measure retracts when you push the button? Imagine reversing that process in space to unspool a sail as tall and wide as a 10-story building from a container the size of a compact fridge,” McNutt said.

The Solar Cruiser project team has set out to demonstrate a larger solar sail than any flown before. “We’ve taken the concept past the drawing board and into development … after years of hard work,” said McNutt, “paving the way for larger and more complex solar sails to take flight.”

Lessons learned

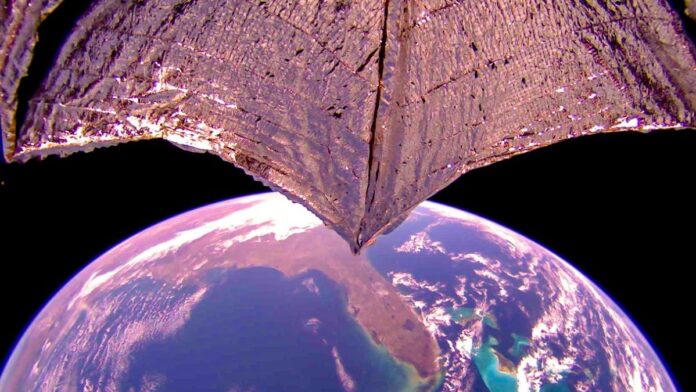

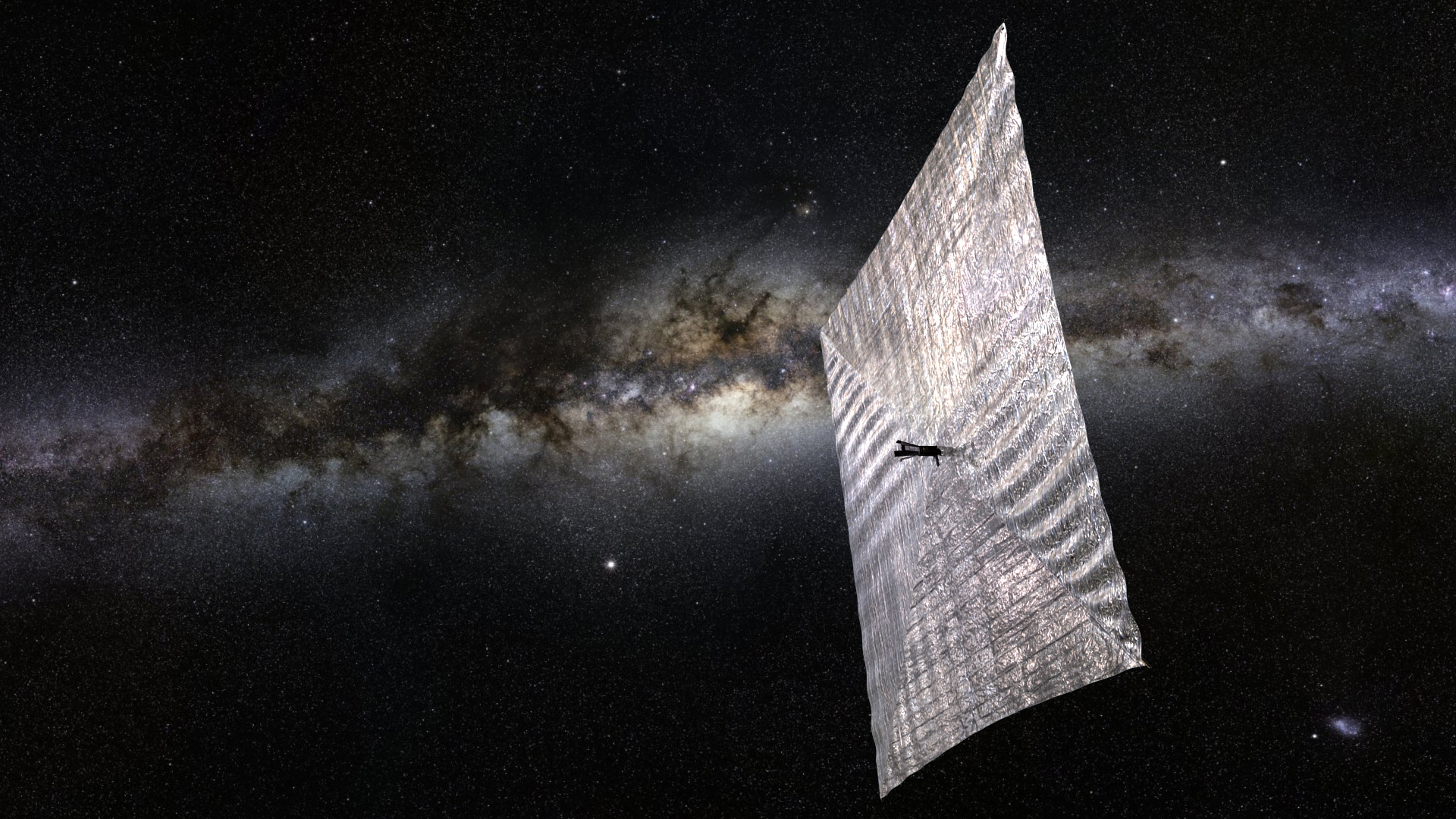

Also pioneering solar sailing is The Planetary Society, the public space exploration advocacy group. Back in 2015, the nonprofit’s LightSail 1 unfurled its sail in Earth orbit in a landmark test. LightSail 1 didn’t perform any actual sailing, but its successor did: LightSail 2 went up in 2019 and circled our planet for nearly 3.5 years, finally reentering Earth’s atmosphere this past November.

“Funded completely by more than 50,000 everyday space enthusiasts from around the world, the LightSail program demonstrated the first controlled solar sailing mission using a small cubesat-sized spacecraft. LightSail 2 raised the profile of solar sailing as a viable propulsion method for small spacecraft to explore the solar system,” said Bruce Betts, chief scientist for The Planetary Society.

During the LightSail program, Betts said that there were a number of detailed lessons learned about the challenges of operating a solar sail mission.

“The LightSail mission helped us explore the challenges of controlling spacecraft orientation, strategies for regular activities to optimize planned rotations of the spacecraft and, at least for LightSail 2, the importance of regularly recalibrating the gyroscopes used to determine rotation rates of the spacecraft,” Betts told Space.com.

The Planetary Society is sharing LightSail information with NASA and other solar sailing missions “that are now lining up to take on the next, more complex generations of solar sailing,” said Betts.

Extreme sailing

One mission headed for its day in the sun is NASA’s Advanced Composite Solar Sail System, or ACS3. It is a technology demonstration using a mix of materials for ACS3’s lightweight booms that roll out from a cubesat.

Then there’s the “extreme solar sailing” development work being conducted by Artur Davoyan of the University of California, Los Angeles and sponsored by NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program.

“We envisage a new generation of breakthrough science missions that were not possible before, from probing fundamental laws of nature at the outskirts of our solar system to peering into distant worlds,” Davoyan explained in a NIAC briefing about his work.

Fabrication and testing of novel ultra-lightweight sail “metamaterials” capable of withstanding the extreme output by the sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona, is one element of Davoyan’s research.

The NIAC-funded study has blueprinted two breakthrough mission concepts. One is the Fast Transit Interstellar Probe, which aims to send a spacecraft 500 astronomical units (AU) from Earth in just 10 years of spaceflight. (One AU is the Earth-sun distance, about 93 million miles or 150 million kilometers. For perspective, Neptune orbits about 30 AU from the sun on average.)

The other is Corona-Net, a potential precursor mission that would send a formation of extreme solar sails to scrutinize the inner heliosphere at high inclinations, far from the sun.

Fast transit

Another NIAC-funded effort proposes the use of “diffractive solar sailing.” This project, led by Amber Dubill of the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, would use diffracted rather than reflected sunlight to propel a craft. This change could lead to a smaller sail, less complex guidance, navigation and attitude-control schemes and reduced power needs, among other attributes.

Dubill envisions circumnavigating the sun with a constellation of diffractive solar sails to provide measurements of the solar corona and magnetic fields.

Les Johnson sees the idea of solar sailing and what it offers — a propulsion technology and science provider — as gaining wider acceptance in the scientific and engineering communities.

“Anything that is requiring constant low-thrust over years is where solar sails really shine,” he said. “Yes, pun intended.”

Leonard David is author of the book “Moon Rush: The New Space Race (opens in new tab),” published by National Geographic in May 2019. A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades.Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).