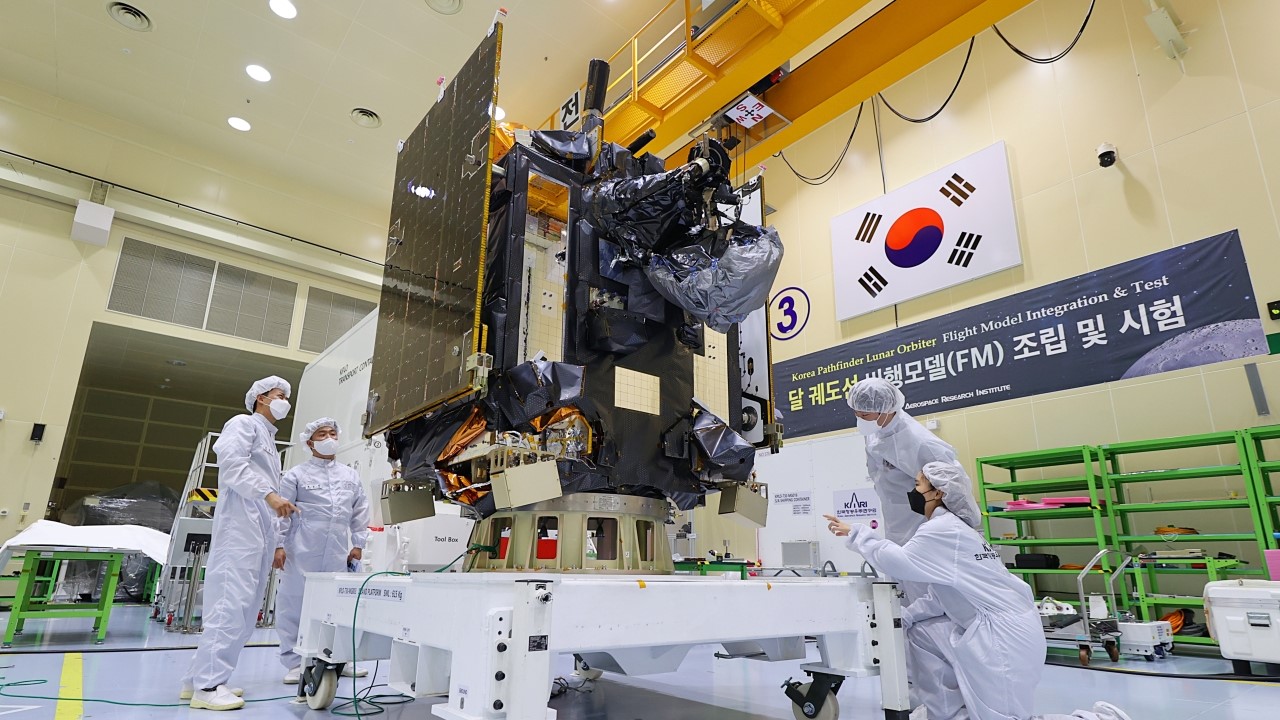

South Korea’s first mission to the moon, the Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter (KPLO), is set to blast off Thursday on a mission to explore magnetic anomalies, search for future landing sites and sniff out rare elements on the moon.

The spacecraft, which is also known as ‘Danuri‘ — a portmanteau of Korean words meaning ‘moon’ and ‘enjoy’ — is currently scheduled to launch on Aug. 4 at 7:08 p.m. EDT (2308 GMT) atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. Upon arrival at the moon, Danuri will enter lunar polar orbit and cruise above the surface at an altitude of 60 miles (100 kilometers).

Not only is Danuri a trailblazer for Korean space exploration, with further missions set to follow, but Danuri will also use six different instruments to conduct important science during its year in operation around the moon. Among other topics, it will focus on the moon’s puzzling magnetism, search for water ice in permanently shadowed craters and test a new experiment designed to improve communication dropouts.

Related: Every mission to the moon

Among Danuri’s instruments is a magnetic-field detector called KMAG, which will measure the strength of magnetic fields in the lunar crust. Scientists hope to learn more about the origin of these fields, and perhaps to discover further clues as to the circumstances surrounding the moon’s formation 4.5 billion years ago.

Scientists know that Earth’s magnetic field is produced by the dynamo effect, wherein layers of electrically-conducting molten iron in the spinning core generate an electric field that induces a resulting magnetic field. But today, the moon’s core is solid.

“We expect that there was such an environment within the central region of the moon at the time of its formation,” Eunhyeuk Kim, who is project scientist for Danuri at KARI, the Korea Aerospace Research Institute, told Space.com in an email interview. “However, the motion of liquid metal ceased at some point.”

In most areas of the moon, all that now remains is some residual trace of magnetism, but there are certain patches where very strong magnetism is present, compared to the rest of the moon. These locations are called lunar magnetic anomalies, and scientists aren’t sure how they formed.

Some of the magnetic anomalies occur at bright ‘lunar swirls,’ which are unusual surface features with, for want of a better word, a ‘squiggly’ shape. Scientists think the swirls might somehow be related to the magnetism, perhaps because the magnetic anomalies mark ancient impacts of metal-rich asteroids that left their magnetic material buried beneath the lunar surface.

“We believe that the KMAG instrument on board Danuri will collect valuable data for the scientific study of these magnetic anomalies,” Kim said.

In addition to KMAG, Danuri will carry a gamma-ray spectrometer called KGRS that will probe for atoms and molecules such as aluminum, silicon, uranium, water and helium-3. The last of these is created by the solar wind, a constant stream of charged particles flowing off the sun, interacting with the lunar surface; scientists think it could be used in nuclear fusion experiments.

The spacecraft is also armed with a polarized camera (PolCam) that will study the bulk properties of the lunar surface material, and a NASA instrument called ShadowCam that is led by Mark Robinson, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University.

ShadowCam will peer into permanently shadowed craters at the lunar poles in search of large quantities of ice that radar observations suggest is present. In order to see into the dark shadows and spot hidden ice, ShadowCam has been designed to be 200 times more sensitive than any previous camera to have gone to the moon.

A fifth payload is a technology demonstrator, the Disruption Tolerant Network Experiment Payload (DTNPL). There’s not always a smooth connection when downloading data from a spacecraft, and often disruptions occur, like experiencing an Internet drop-out while downloading files on your home computer.

“If disruption is expected quite often, then you need a way around it, such as not re-starting downloads from the spacecraft from the beginning, but from the point at which the disruption happened,” Kim said. DTNPL will test a system that is able to do just that. The technology has already been implemented successfully at the International Space Station, 250 miles (400 km) from Earth’s surface. Now Danuri will seek to verify for the first time that the technology also can work successfully at much greater distances beyond Earth orbit.

Danuri is described as a pathfinder because it is paving the way for South Korea to expand its space exploration program. And the inclusion of Danuri’s final science instrument, called the Lunar Terrain Imager (LUTI), hints at the nation’s ambitions of a landed mission.

“LUTI will take images of potential landing sites, specifically for a lunar landing mission targeted for the early 2030s,” Kim said. KARI has canvased the opinions of members of the Korean lunar-science community to generate a list of dozens of potential landing sites to image.

So far, only the U.S., the Soviet Union and China have successfully landed on the moon, so for South Korea to follow in their footsteps would be a very big step. “We expect that it is necessary to build up new space technologies, in addition to accumulated technologies from the orbiter mission, for a safe lunar landing mission,” Kim said.

And South Korea’s ambitions are not limited to a jaunt or two to the moon. “Our overall plan is to head to the asteroids and Mars after that,” Kim said. The nation is even developing plans for ambitious sample-return missions, and although Danuri is launching with SpaceX, the nation has also developed its own rocket.

After its launch, Danuri will spend four and a half months traveling to lunar polar orbit and will begin its one-year mission proper in January 2023, starting with a month-long commissioning phase.

Follow Keith Cooper on Twitter @21stCenturySETI. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.