A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket upper stage is poised to slam into the moon one month from today (Feb. 4).

In February 2015, the Falcon 9 launched the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR), a joint mission between the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and NASA.

The rocket carried DSCOVR toward the Earth-sun Lagrange Point 1 (L1), a gravitationally stable spot about 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth. After getting there, the upper stage ended up pointing away from our home planet.

“This rendered a deorbit burn to dispose of it in our planet’s atmosphere impractical, while the upper stage also lacked sufficient velocity to escape the Earth-moon system. Instead it was left in a chaotic sun-orbiting orbit near the two bodies,” European Space Agency (ESA) officials wrote in a statement Wednesday (Feb. 2).

The upper stage’s time in space is now almost up: It will hit the moon on March 4, observers have calculated.

Related: The evolution of SpaceX’s rockets in pictures

Regulatory regime

Human-made objects have been intentionally steered into the moon before, starting as early as the 1950s. The practice was common during the Apollo program, with rocket upper stages even used to induce “moonquakes” for surface seismometers to pick up.

But the coming SpaceX moon crash is quite different, marking “the first time that a human-made debris item unintentionally reaches our natural satellite,” ESA officials wrote. (“Debris item” does not include spacecraft that have crashed while trying to land on the moon, such as Israel’s Beresheet probe in 2019.)

“The upcoming Falcon 9 lunar impact illustrates well the need for a comprehensive regulatory regime in space, not only for the economically crucial orbits around Earth but also applying to the moon,” Holger Krag, head of ESA’s Space Safety Program, said in the same statement.

“For international spacefarers, no clear guidelines exist at the moment to regulate the disposal at end of life for spacecraft or spent upper stages sent to Lagrange points,” ESA officials wrote in the statement. “Potentially crashing into the moon or returning and burning up in Earth’s atmosphere have so far been the most straightforward default options.”

Credible forecasts

The Falcon 9 upper stage will strike the moon on March 4 at 7:25 a.m. EST (12:25 GMT) on the lunar far side near the equator, according to observers’ calculations. That’s just an estimate, albeit a precise one; followup observations should sharpen the accuracy of forecasts.

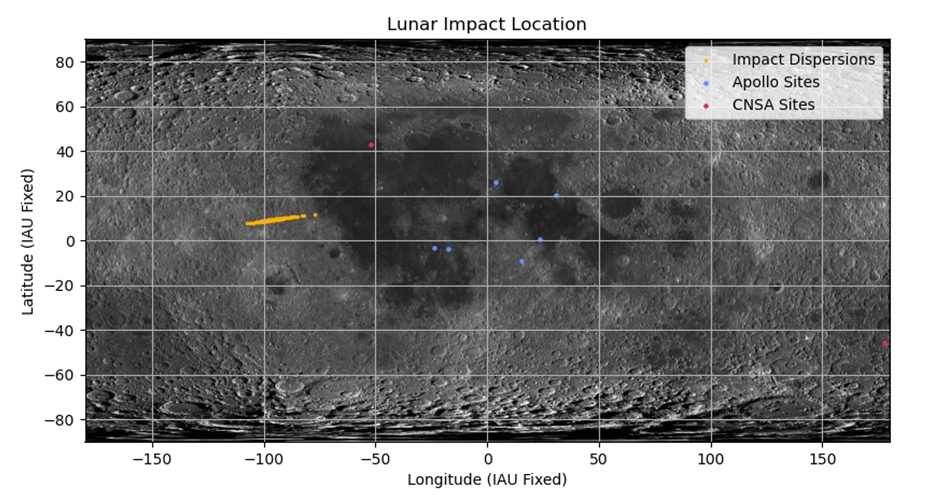

One such calculation comes from astrodynamics engineer Michael Thompson, of Advanced Space in Westminster, Colorado. He’s generated a plot and a visual to show where the upper stage may crash.

Thompson built upon the work by Bill Gray of Project Pluto, who collects and analyzes observations of near-Earth objects. It was Gray who discovered the crash course of the SpaceX upper stage.

Project Pluto posts a subset of raw observations made by users around the world. Using these observations, Thompson performed his own orbit determination process in addition to the processes run by Gray.

Advanced Space generated predictions currently showing an impact west of the Sea of Tranquility, very similar to the prediction generated by Gray.

Impact will be near the lunar limb as viewed from Earth, according to these calculations. Most of the distribution lies slightly on the moon’s far side. Based on current data, the impact is not expected to be near any NASA Apollo or Chinese lunar exploration sites.

Related: The greatest moon crashes of all time

Still uncertain

The impact may or may not be visible from Earth, Thompson noted.

The predicted impact zone is far away from the current location of China’s Chang’e 4 lander-rover duo; it’s much closer to the lunar limb than fully over on the far side.

Even given the large uncertainties in the attitude of the rocket body and the resulting uncertainties in the solar radiation pressure effects on it, an impact much closer to Chang’e 4 is unlikely, Thompson added.

The uncertainty will come down a good bit more once additional observations are made this month.

Assessing observations

“NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) will not be in a position to observe the impact as it happens,” a NASA statement sent to Inside Outer Space explained.

“However, the mission team is assessing if observations can be made to any changes to the lunar environment associated with the impact and later identify the crater formed by the impact. This unique event presents an exciting research opportunity,” the NASA statement added.

“Following the impact, the [LRO] mission can use its cameras to identify the impact site, comparing older images to images taken after the impact. The search for the impact crater will be challenging and might take weeks to months.”

Leonard David is author of “Moon Rush: The New Space Race” (National Geographic, 2019). A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.