Staggering growth in Starlink collision-avoidance maneuvers in the past six months is sparking concerns over the long-term sustainability of satellite operations as thousands of new spacecraft are poised to launch into orbit in the coming years.

SpaceX‘s Starlink broadband satellites were forced to swerve more than 25,000 times between Dec. 1, 2022, and May 31, 2023 to avoid potentially dangerous approaches to other spacecraft and orbital debris, according to a report filed by SpaceX with the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) on June 30. That’s about double the number of avoidance maneuvers reported by SpaceX in the previous six-month period that ran from June to November 2022. Since the launch of the first Starlink spacecraft in 2019, the SpaceX satellites have been forced to move over 50,000 times to prevent collisions.

The steep increase in the number of maneuvers worries experts because it follows an exponential curve, leading to concerns that safety of operations in the orbital environment might soon get out of hand.

“Right now, the number of maneuvers is growing exponentially,” Hugh Lewis, a professor of astronautics at the University of Southampton in the U.K. and a leading expert on the impact of megaconstellations on orbital safety, told Space.com. “It’s been doubling every six months, and the problem with exponential trends is that they get to very large numbers very quickly.”

Related: How many satellites can we safely fit in Earth orbit?

1 million maneuvers by 2028

Data compiled by Lewis shows that, in the first half of 2021, Starlink satellites conducted 2,219 collision-avoidance maneuvers. The number grew to 3,333 in the following six-month period ending in December 2021 and then doubled to 6,873 between December 2021 and June 2022. In the second half of 2022, SpaceX had to alter the paths of its satellites 13,612 times to avoid potential collisions. In the latest report to the FCC, the company declared 25,299 collision-avoidance maneuvers over the past six months, with every satellite having been made to move an average of 12 times.

“Right now, every six months, the number of maneuvers that are being made doubles,” said Lewis. “It has gone up by a factor of 10 in just two years, and if you project that out, you’ll have 50,000 within the next six-month period, then 100,000 within the next, then 200,000, and so on.”

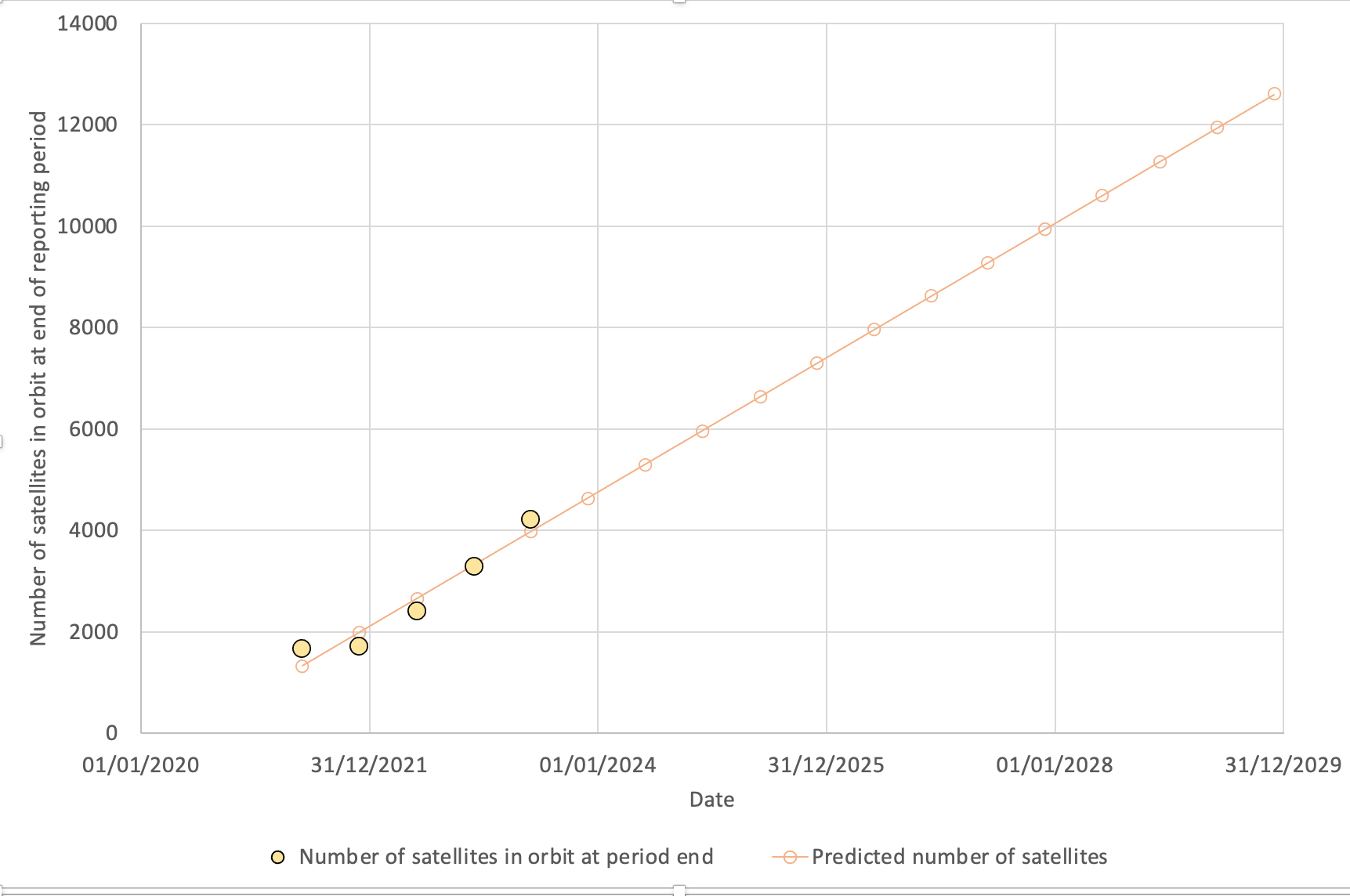

If the trend continues, by 2028, Starlink satellites will have to maneuver nearly a million times in a half-year to minimize the risk of orbital collisions. And Lewis doesn’t expect such growth to slow down any time soon. SpaceX has so far deployed about one-third of its planned first-generation constellation of 12,000 spacecraft and has been launching at a regular pace of over 800 satellites per year, a trend that is expected to continue for the foreseeable future.

The first-generation Starlink constellation is, however, just the beginning. The FCC has partially approved plans for the second-generation Starlink constellation, which could consist of up to 30,000 satellites. And other players all over the world, including Amazon with its Project Kuiper and China with Guowang, are scrambling to secure orbital slots with their respective regulators.

Like swerving on a highway every 10 meters

According to Joanne Wheeler, a satellite regulations expert at Alden Legal and chair of the U.K.-based Satellite Finance Network, more than 1.7 million satellites have been registered with the International Telecommunication Union, the United Nations’ agency overseeing the use of radio frequencies by satellites. Although not all of those plans are likely to come to fruition, the numbers in question are so high that experts such as Lewis question whether order in orbit can be maintained.

“If we’re expecting by the end of this decade to have 100,000 active satellites, then my suspicion is that the number of maneuvers collectively that all spacecraft operators will be making will be just enormous,” Lewis said. “You’re making maneuvers to mitigate the high-risk events, but it’s like driving down the highway and swerving every 10 meters to avoid a collision. It’s arguably not safe.”

Currently there are about 10,500 satellites orbiting our planet, 8,100 of which are operational, according to the European Space Agency. Things only started to get so congested fairly recently. For example in 2019, there were only about 2,300 active satellites circling the planet, according to Statista. The main driver of the growth is Starlink, by far the largest satellite constellation ever assembled.

New satellites are not the only cause behind the increasing need for orbital swerving. The amount of space debris — defunct spacecraft, old rocket stages and various fragments — also continues to grow, making it increasingly difficult for operators to keep their spacecraft safe.

SpaceX currently conducts an avoidance maneuver every time orbital models show a probability higher than 1 in 100,000 that one of the Starlink satellites will cross another object’s path. That threshold is 10 times lower than the standard upheld by NASA and other international agencies.

Lewis, however, questions whether SpaceX will be able to maintain such a high standard as the number of “conjunction alerts” continues to snowball. He adds that, despite the company’s efforts, the residual risk of a collision will continue to rise as well.

Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and another frequently heard voice of caution in the satellite megaconstellations debate, agrees with Lewis: “SpaceX are convinced that they can handle the increasing maneuver load,” McDowell told Space.com in an email. “I am not convinced that SpaceX have properly taken into account the non-statistical errors (the potential for independent and unpredictable screwups combining to give a bad result – a collision) – so I am concerned that we are operating at the edge of what is safe.”

Starlink relies on an autonomous collision avoidance system that instructs satellites to maneuver based on models of orbital trajectories of objects in space. These models provide alerts several days in advance and may not always get it right. Moreover, other factors, such as the changes in the density of Earth’s atmosphere at high altitudes caused by space weather, may affect the accuracy of these calculations.

“There is a concern about the conjunctions that are occurring where no maneuvers are being made,” said Lewis. “You could argue that the probability [of a collision in these cases] is very low, but given the very large number of them, they represent a quite substantial risk. It’s like buying a ticket in a lottery. If you buy just one, you are unlikely to win, but if you buy a million tickets, you stand a pretty good chance.”

Lewis expects that, unless regulators cap the number of satellites in orbit, collisions will soon become a regular part of the space business. Such collisions would lead to rapid growth in the amount of space debris fragments that are completely out of control, which would lead to more and more collisions. The end point of this process might be the Kessler Syndrome, a scenario predicted in the late 1970s by former NASA physicist Donald Kessler. Depicted in the 2013 Oscar-winning movie “Gravity,” the Kessler Syndrome is an unstoppable cascade of collisions that might render parts of the orbital environment completely unusable.