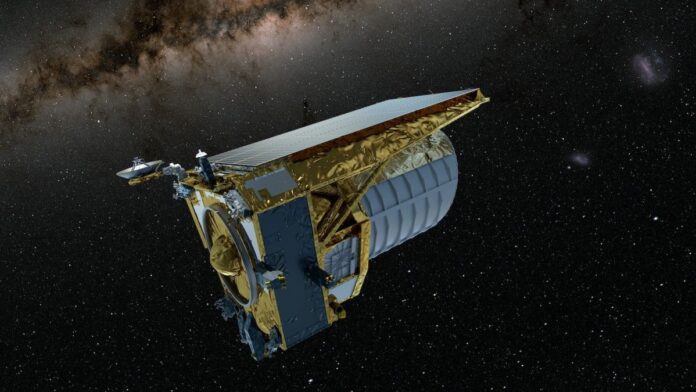

A European probe is just one week away from launching on its mission to help unveil the dark universe.

Euclid, a dark matter and dark energy hunter, is scheduled to launch atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Florida’s Cape Canaveral Space Force Station on July 1 at 11:11 a.m. EDT (1511 GMT). The liftoff will be carried live here at Space.com, and you can watch it for free.

Euclid aims to map the extent and influence of the dark universe to a sharper degree than ever before, with numerous implications: how the universe grew in its early days, how galaxies come together and why the expansion of the universe is accelerating.

Related: If dark matter is ‘invisible,’ how do we know it exists?

“Dark energy and dark matter reveal themselves by the fairly subtle changes they make to the appearance of objects in the visible universe; otherwise we don’t know about them,” René Laureijs, Euclid project scientist, said in a livestreamed European Space Agency briefing today (June 23).

Laureijs pointed to phenomena like gravitational lensing, which brings distant objects into view through the gravitational effects of a large foreground object (like a galaxy). Euclid will be able to see these effects more sharply than any observatory before it, given that it will operate in deep space: It’s headed for the Earth-sun Lagrange Point 2 (L2), a gravitationally stable spot about 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from our planet.

“They must show somewhere, and it’s very subtle,” Laureijs said of the effects, which will be easier to map and model with Euclid’s sharp vision. Two instruments that specialize in infrared (heat) and visual wavelengths will work together to image large swaths of the sky, to infer where dark matter may be lurking by charting its effects on visible objects.

Related: The Euclid spacecraft will transform how we view the ‘dark universe’

“The field of view of the telescope is half a square degree of sky at a time; that’s really big if you compare it to the Hubble Space Telescope, and huge if you compare it to the James Webb Space Telescope,” Will Percival, primary science coordinator for the Euclid space mission at Canada’s University of Waterloo, told Space.com in an individual interview.

“We will look at a patch and tape an observation. Because we’re doing these really precise and weak ‘lensing’ observations, we don’t want to drift scan. We (therefore) want to move the telescope to another patch and take that patch,” Percival continued. “Then we stitch together this survey through different exposure numbers, different data patterns, all butting up to each other like bricks in a wall until we’ve observed the whole sky.”

Euclid’s commissioning period will last roughly eight months, including a one-month transit to L2, the same orbit as JWST.

Operating in stable gravitational conditions that minimize fuel usage, Euclid will carefully test out its instruments and systems before being certified for full operations somewhere around April 2024, assuming the launch occurs on time and commissioning goes well.

The first Euclid images will be released a few months after launch and sometime during the commissioning period, Percival said.

What Euclid will observe exactly is under tight guard, but Percival said the “performance verification phase” of commissioning will include images of “well-known nearby objects” to see how Euclid performs against the ground-based observatories that usually do dark energy surveys. Such images, he noted, also aim to get the public engaged in the mission.

Euclid is to scheduled to operate for at least six years. “We are observing 15,000 square degrees at a resolution that has never been done before, to a depth that has never been done before,” Percival said.

It’s hard to predict just what discoveries could be made from the vast amounts of data Euclid will send home, he added. “The discovery space for finding new classes of objects by mining that data is huge.”

Elizabeth Howell will travel to Florida to cover Euclid’s launch under co-sponsorship by Canadian Geographic magazine and Canada’s University of Waterloo. Space.com has independent control of its news coverage.