Sunspots are dark, planet-size regions of strong magnetic fields on the surface of the sun. They can spawn eruptive disturbances such as solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs).

These regions of the sun appear darker because they are cooler than their surroundings. The central dark region, the umbra, is about 6,300 degrees Fahrenheit (3,500 degrees Celsius), whereas the surrounding photosphere is about 10,000 F (5,500 C), according to the National Weather Service (NWS).

The frequency and intensity of sunspots visible on the surface indicate the level of solar activity during the 11-year solar cycle that is driven by the sun’s magnetic field. Sunspots are our window into the sun’s complicated magnetic interior, and they have fascinated solar observers for hundreds of years.

Related: The Carrington Event: History’s greatest solar storm

How do sunspots form?

Sunspots form when concentrations of magnetic field from deep within the sun well up to the surface, according to the European Solar Telescope (opens in new tab). They consist of a central darker region, known as the umbra, and a surrounding region, known as the penumbra.

(opens in new tab)

Though scientists don’t fully understand how sunspots form, researchers generally accept a theory first proposed by American astronomer Horace Babcock in 1961 (opens in new tab): that sunspots are forged by the sun’s magnetic field.

Imagine the sun’s magnetic field as loops of rubber bands, with one end attached to the north pole and the other to the south pole. As the sun rotates at different speeds, with the equator rotating faster than the poles, a “differential rotation” is created, according to Royal Museums Greenwich (opens in new tab).

How big is a sunspot?

Sunspots are, on average, about the same size as Earth, though they can vary from hundreds to tens of thousands of miles across, according to Cool Cosmos (opens in new tab).

As the sun rotates, these magnetic loop “rubber bands” get more wound up (both tighter and more complicated). Eventually, the magnetic fields “snap,” rise and break the surface. This disturbance in the sun’s magnetic field forms pores that can grow and join together to form larger pores, or proto-spots, that eventually become sunspots. A group of sunspots is known as an active region.

The magnetic field in active sunspot regions can be some 2,500 times stronger than Earth’s, according to the NWS. The strong magnetic field inhibits the influx of hot, new gas from the sun’s interior, causing sunspots to be cooler and appear darker than their surroundings, relatively speaking. According to the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (opens in new tab) (UCAR), if you could cut out a standard sunspot from the sun and place it in the night sky, it would appear as bright as a full moon.

Sunspots and the solar cycle

(opens in new tab)

Sunspots form over periods of days to weeks and can remain on the surface for months before eventually disappearing.

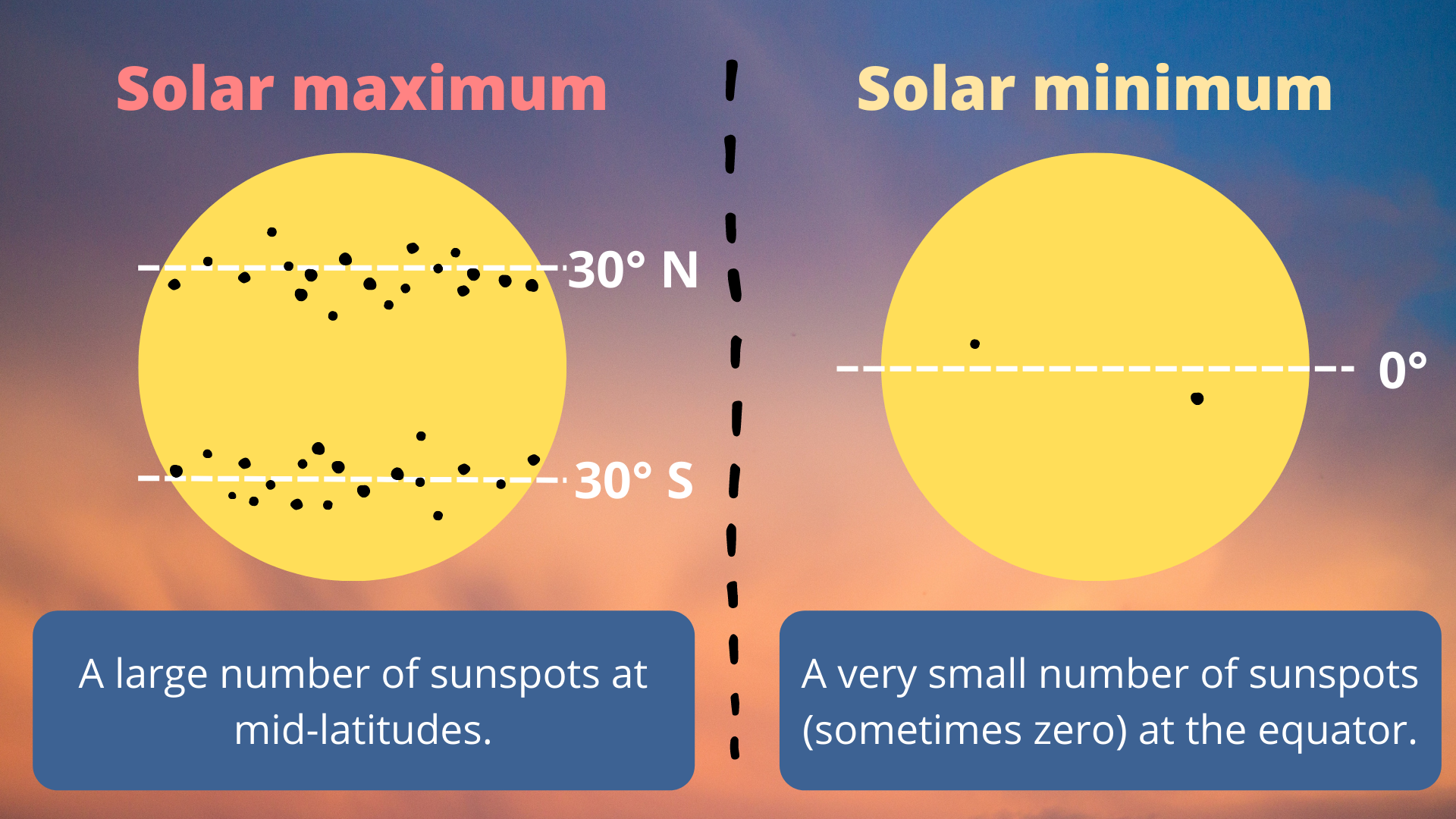

The total number of sunspots varies during the 11-year solar cycle, sometimes called the sunspot cycle, with the peak of sunspot activity coinciding with the solar maximum and a sunspot hiatus occurring with the solar minimum, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center (opens in new tab) (SWPC).

Sunspot positions also change throughout the solar cycle. During the solar maximum, many sunspots are found along mid-latitudes (approximately 30 degrees north and 30 degrees south). Then, sunspots gradually move toward the equator, where few are found during the solar minimum. Sometimes, no sunspots are visible during the solar minimum.

(opens in new tab)

Though the 11-year solar cycle is fairly consistent, between 1645 and 1715, very few sunspots were observed. Between 1672 and 1699, fewer than 50 sunspots were recorded, according to Physics World (opens in new tab). For comparison, during a “normal” solar minimum there are usually 12 to more than 100 sunspots per year.

This period of severely reduced solar activity came to be known as the “Maunder minimum,” after British astronomer Edward Walter Maunder, who — along with his wife, Annie — discovered the lack of activity from the records in 1890, according to The Times (opens in new tab).

Sunspots today

The sun is experiencing solar cycle 25, in which solar activity is currently on the rise, resulting in a greater emergence of sunspots. To see what sunspots look like today, check out this observing page (opens in new tab) from the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO).

Who discovered sunspots?

There is some debate about who discovered sunspots. According to the Chandra X-ray Center (opens in new tab), the earliest records of solar activity are from Chinese astronomers around 800 B.C. Chinese and Korean astronomers frequently observed sunspots, according to the Chandra X-ray Center. However, there are no known early illustrations of such observations.

The earliest known drawings of solar activity appeared many years later, in 1128, in John of Worcester’s chronicle. “In the third year of Lothar, emperor of the Romans, in the twenty-eighth year of King Henry of the English … on Saturday, 8 December, there appeared from the morning right up to the evening two black spheres against the sun,” Worcester wrote.

(opens in new tab)

Just five days after Worcester described a large sunspot group, Korean astronomers reported that they’d observed a red vapor that “soared and filled the sky.” This description suggests the presence of the aurora borealis, or northern lights, at relatively low latitudes.

In 1610, aided by a telescope, English astronomer Thomas Harriot detailed his solar observations according to NASA (opens in new tab) with detailed notes and sketches. His drawings are the earliest known pictorial record (opens in new tab) of sunspots.

A year later, David and Johannes Fabricius (father and son) independently discovered sunspots. A couple of months after that, Johannes Fabricius became the first person in the West to publish anything on the subject of sunspots, in a pamphlet titled “On the Spots Observed in the Sun and their Apparent Rotation with the Sun.”

According to NASA, there were two other independent sunspot discoveries at the same time in 1611. Galileo Galilei and Jesuit Christoph Scheiner competed over who deserved the credit for discovering sunspots. Unbeknownst to the quarreling astronomers, sunspots had already been observed and recorded hundreds of years earlier, so their lifelong feud was futile.

Observing sunspots

(opens in new tab)

NEVER look directly at the sun with binoculars, a telescope or your unaided eye without using special protection. Astrophotographers and astronomers use special filters to safely observe the sun. Here’s our guide on how to observe the sun safely.

Sunspots have been observed for hundreds of years and continue to be the main focus for scientists who want to learn more about the solar cycle and assess the risk of space weather, such as solar flares and CMEs.

Our current picture of solar activity would not be as clear without the work of Japanese astronomer Hisako Koyama. Between 1947 and 1996, Koyama sketched sunspots from the roof of the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo, using a 20-centimeter (8 inches) refracting telescope. For over 40 years, Koyama made more than 10,000 sunspot observations (opens in new tab) that have shaped solar science and our understanding of space weather, according to a commentary about her work (opens in new tab) published in the journal Space Weather.

(opens in new tab)

Nowadays, scientists at NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center analyze sunspot regions daily to access their threats. They monitor and record changes in sunspot size, number and position to assess the likelihood of a solar flare and/or CME from an active region.

The World Data Center for the Sunspot Index and Long-term Solar Observations (opens in new tab) at the Royal Observatory of Belgium also tracks sunspots and records the highs and lows of the solar cycle to evaluate solar activity and improve space weather forecasting.

Scientists classify sunspot groups to assess which are more likely to incite a solar flare or CME. To do so, researchers at the Mount Wilson Observatory in California have come up with a set of classifications to assign to sunspot groups, according to SpaceWeatherLive (opens in new tab).

Each day, sunspots are counted and receive both a magnetic classification and a spot classification. Another classification system is based on the Zürich/McIntosh system and is designed to classify sunspots to inform scientists about how long the sunspot will last its complexity and size, SpaceWeatherLive says (opens in new tab).

Additional resources

If you’re interested in viewing sunspots for yourself, you can see how to make your own pinhole viewer so you can observe the sun responsibly. Learn more about sunspots and solar rotation with the National Schools’ Observatory (opens in new tab). Read more about the history of sunspots and the controversy surrounding their “discovery” with The Galileo Project from Rice University (opens in new tab).

Bibliography

Babcock, H. W. (1961). The topology of the sun’s magnetic field and the 22-year cycle. The Astrophysical Journal, 133, 572. https://doi.org/10.1086/147060 (opens in new tab)

Chandra X-ray Center. (n.d.). The Historical Sunspot Record. [PDF] https://chandra.harvard.edu/edu/formal/icecore/The_Historical_Sunspot_Record.pdf (opens in new tab)

Cooper, K. (2022, April 5). Astronomers see star enter a ‘Maunder minimum’ for the first time. Physics World. https://physicsworld.com/a/astronomers-see-star-enter-a-maunder-minimum-for-the-first-time/ (opens in new tab)

Fox, K. C. 2011, March 9). Celebrating 400 years of sunspot observations. NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sunearth/news/400yrs-spots.html#:~:text=Galileo%20and%20the%20German%20Jesuit,a%20telescope%20in%20December%201610 (opens in new tab)

González, N. (n.d.). How do sunspots form? European Solar Telescope. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://est-east.eu/?option=com_content&view=article&id=924&Itemid=622&lang=en (opens in new tab)

IPAC-Caltech. (n.d.). How big is a sunspot? Cool Cosmos. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://coolcosmos.ipac.caltech.edu/ask/12-How-big-is-a-sunspot-#:~:text=The%20average%20sunspot%20is%20about,many%20times%20larger%20that%20Earth (opens in new tab)

Knipp, D., Liu, H., & Hayakawa, H. (2017). Ms. Hisako Koyama: From amateur astronomer to long‐term solar observer. Space Weather, 15(10), 1215-1221. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017SW001704 (opens in new tab)

National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo. (n.d.). Observation of sunspots 1947-1996. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.kahaku.go.jp/research/db/science_engineering/sunspot/ (opens in new tab)

National Weather Service. (n.d.). The sun and sunspots. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.weather.gov/fsd/sunspots (opens in new tab)

Parsec vzw. (n.d.). The classification of sunspots after Malde. SpaceWeatherLive. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.spaceweatherlive.com/en/help/the-classification-of-sunspots-after-malde.html (opens in new tab) .

Parsec vzw. (n.d.). The magnetic classification of sunspots. SpaceWeatherLive. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.spaceweather.live/en/help/the-magnetic-classification-of-sunspots.html (opens in new tab)

Royal Museums Greenwich. (n.d.). Sunspots. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/sunspots (opens in new tab)

SILSO. (2021, July 16). World Data Center for the production, preservation and dissemination of the international sunspot number. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.sidc.be/silso/ (opens in new tab)Simons, P. (2018, December 20). Husband and wife team behind the Maunder minimum. The Times. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/husband-and-wife-team-behind-the-maunder-minimum-b2pts37bf (opens in new tab)

Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (n.d.). SOHO EIT 171 latest image. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://soho.nascom.nasa.gov/data/realtime/eit_171/512/ (opens in new tab)