It’s been one year since we saw the first official images taken by the groundbreaking James Webb Space Telescope.

Since then, the telescope has been hard at work collecting data on our universe. In just one year, researchers have published over 750 pieces of peer-reviewed scientific literature using or citing data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST or Webb), according to the Space Telescope Science Institute. From data on some of the universe’s first galaxies to a greater understanding of our own solar system, JWST has begun to deliver on its promise of observing our universe in more detail than ever before. And it’s just getting started, with decades of science predicted ahead of it.

“Kids that are in grade school today [could] be using this telescope,” Stefanie Milam, the JWST deputy project scientist for planetary science, told Space.com. “This is for the next generation.”

Here is what JWST’s been up to in its first year, and what might be next for the telescope.

Related: 12 amazing James Webb Space Telescope discoveries across the universe

Groundbreaking discoveries

So far, JWST has completed hundreds of research projects, including many related to capturing the most distant observable galaxies, which, because of how long light takes to travel to us, are also some of the very first galaxies in the universe.

JWST has managed to capture galaxies as distant as 13.4 million light-years away, just 320 million years after the Big Bang. Some of these galaxies have surprising qualities, said Milam, such as unexpectedly large size or higher rates of star formation than expected, according to Nature.

Another area JWST has made strides in is exoplanet research, including taking detailed measurements of the atmospheres of exoplanets, for instance those in the TRAPPIST-1 system, a group of seven exoplanets about 40 light-years away orbiting a small star.

The system is the largest known collection of Earth-sized exoplanets in a star’s “habitable zone,” the distance from a star where scientists think there might be conditions that could sustain life. In research published in March, researchers were able to use infrared radiation data from a secondary eclipse, or when a planet passed behind TRAPPIST-1, to learn that TRAPPIST 1-b, the innermost planet, does not have an atmosphere.

Closer to home, Webb has made some surprising discoveries in our asteroid belt. In a study Milam worked on published in May, researchers used JWST to identify the first known comet surrounded by water vapor in the asteroid belt. Previously, comets containing water ice had only been found in the faraway Oort Cloud and the Kuiper Belt.

“Water vapor in the asteroid belt is huge,” said Milam. “That means there’s some kind of mechanism preserving water ice in an asteroid-like body that close to our sun.”

Exceeding expectations from the start

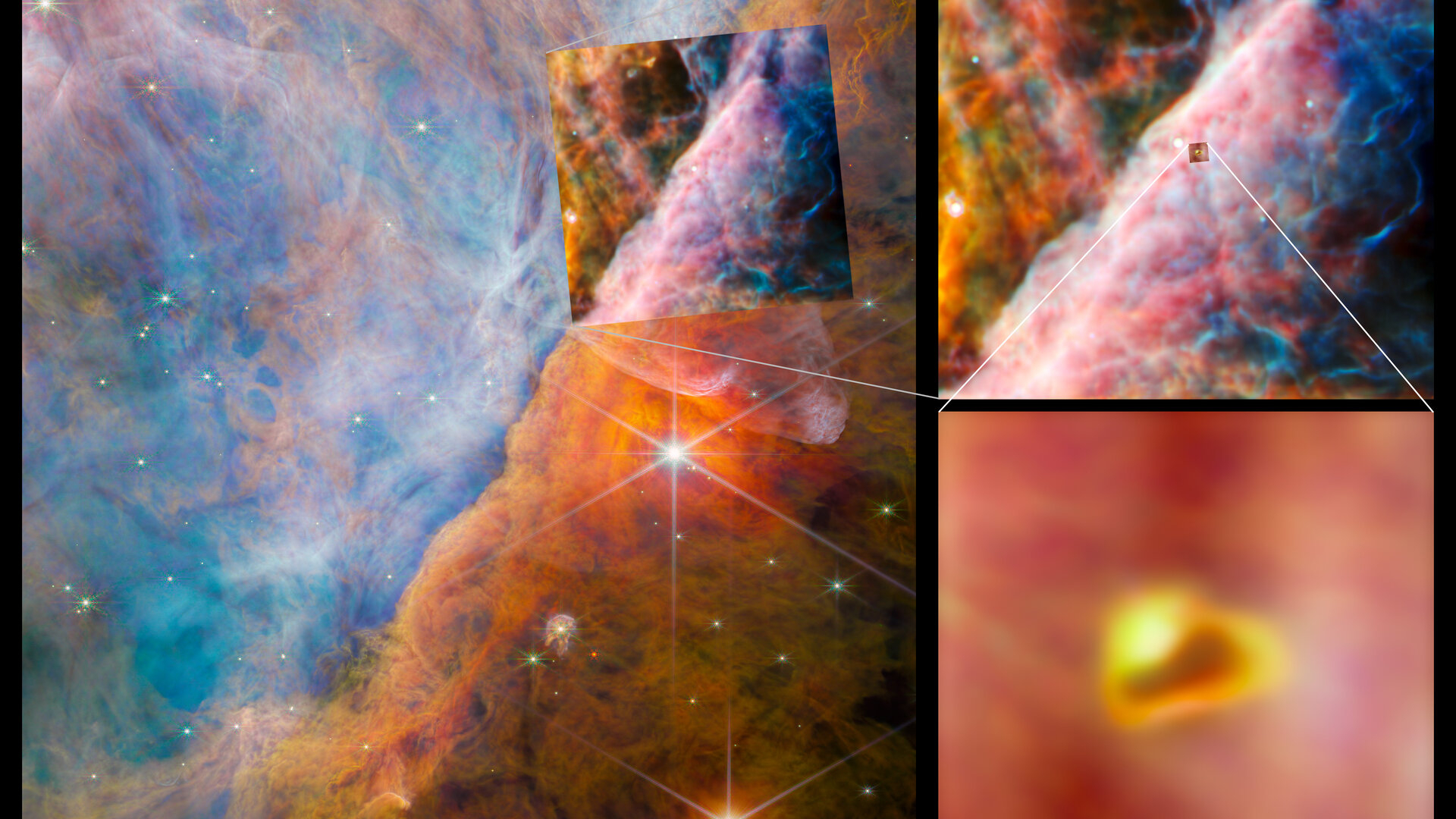

Every observation JWST makes also benefits from its mind-boggling optics. JWST was required to have a tiny diffraction limit of just two microns, said Milam. But the telescope ended up even more precise — its diffraction limit is currently 1.1 microns, meaning that it can resolve objects that, from the telescope, appear around the size of a small single bacterium.

“Everyone’s […] getting even better data than they had hoped for” because of these optics, said Milam.

On top of the amazing quality of observations, the telescope’s launch went so well that it conserved notably more fuel than scientists were predicting. Though NASA first expected JWST to last about 10 years or less, now it’s predicted to continue operating for 20 years, into the 2040s.

What’s next

In the next year, researchers will build on what they’ve learned this year using JWST, continuing to push the telescope’s capabilities and boundaries. For instance, Milam said, it’s possible the telescope might be able to discover an even more distant galaxy.

Of course, there have been some challenges when it comes to JWST. In May 2022, before its first images were even released, a larger-than-expected micrometeoroid hit JWST, causing a tiny but detectable amount of damage to the telescope. A micrometeoroid impact this large is uncommon, said Milam, and scientists are continuing to develop ways to make sure future impacts don’t damage the telescope.

Still, she said, things could hardly be going better, with JWST continuing to reveal more questions to answer about our universe.

“Every time we look at something, it opens up a whole new can of worms,” she said.