Inside All About Space issue 131, on sale now, discover everything you need to know about the universe from the Big Bang to its ultimate fate.

For this cover feature, All About Space meets the people behind the experiments searching for answers to how our universe began. From recreating the Big Band at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) with the particle-smashing Large Hadron Collider to observing the aftermath with the Space Science Institute in Maryland.

The latest issue seeks to answer questions such as would we notice if the universe stopped expanding? or how do we know that the universe is a cosmic latte color?

Related: Is there anything beyond the universe?

Elsewhere in this issue, you can find an in-depth planet profile on Jupiter. The gas giant has a lot to tell us and Juno is on the case.

The latest issue also features an interview with Christopher J. Ferguson, a retired US Navy Captain and NASA astronaut who now works at Boeing where he has helped build a new generation of space vehicles with their CST-100 capsule under contract from NASA.

We also have an in-depth stargazer section filled with useful information on what to look out for in the sky, including naked eye and binocular targets and a guide to getting the best views of the solar system.

Take a peek below at All About Space issue 131’s biggest features

The universe explained

(opens in new tab)

The universe almost seems to have come out of nowhere. A concoction of high temperatures and a thick gloop of exotic particles that would go into an overdrive of expansion through several phases of varying conditions to create the universe as we see it today some 13.8 billion years later: the Big Bang, creator of time and space — or at least that’s what our current understanding of how our universe sprang into existence leads us to believe.

But what we have come to learn about the cosmos’ somewhat mysterious past wasn’t always as tacked down, going back to the days of Georges Lemaître, who would later be dubbed the father of the Big Bang theory. What the Belgian priest, astronomer and professor of physics did suspect back in 1927, based on his solutions to Albert Einstein’s equations, was that the universe must have sparked into life from a single point at the beginning of time before driving headlong into an expansion.

Read the full feature in the latest All About Space (opens in new tab).

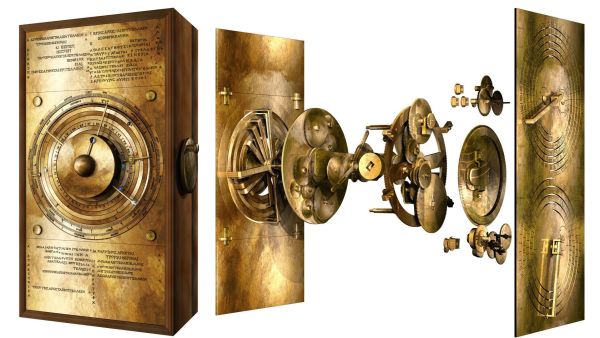

Unlocking the secrets of the Antikythera Mechanism

(opens in new tab)

In 1900, sponge diver Elias Stadiatis was in the waters off the coast of the Greek island of Antikythera when he made a startling discovery. What lay before him appeared to be rotting corpses and horses scattered over the seafloor amid the remains of a Greek shipwreck. After a team of divers were sent to take a look later that year, it didn’t take long to work out what Stadiatis had seen: a treasure trove of bronze and marble statues, some of which dated back to the 4th century BCE. But the divers didn’t know they had also recovered something even more remarkable.

An object roughly the size of a large book was discovered in the depths of the wreck in 1901. The following year, archaeologist Spyridon Stais happened to be looking at the book-sized lump and it began to crumble. As it did so, he could see a corroded piece of bronze embedded with precision gear wheels but most of the technology was obscured by corrosion.

Read the full feature in the latest All About Space (opens in new tab).

How are auroras formed on other planets?

(opens in new tab)

The shimmering northern lights, or aurora borealis, are a natural light show that occurs in a loop around the poles. The southern version is known as aurora australis. Auroras occur when charged particles emanating from the Sun – the solar wind – crash into the upper atmosphere. A mixture of electrons, protons and helium nuclei, they lose energy as they collide with atmospheric gas molecules. These gas molecules become ionized – some of their electrons are pulled away – and the gases form a glowing plasma.

The gas mix governs the colors we see. Red is generated by low concentrations of oxygen at high altitudes. This changes to green as oxygen density increases, with blue generated by nitrogen. Pink, yellow and orange have all been observed, presumably due to the layering of different amounts of red, green and blue.

Read the full feature in the latest All About Space (opens in new tab).