The Hunga Tonga volcanic eruption that shook the South Pacific Ocean in January will not affect Earth’s climate despite sending clouds of ash dozens of miles high into the atmosphere, a new study confirmed.

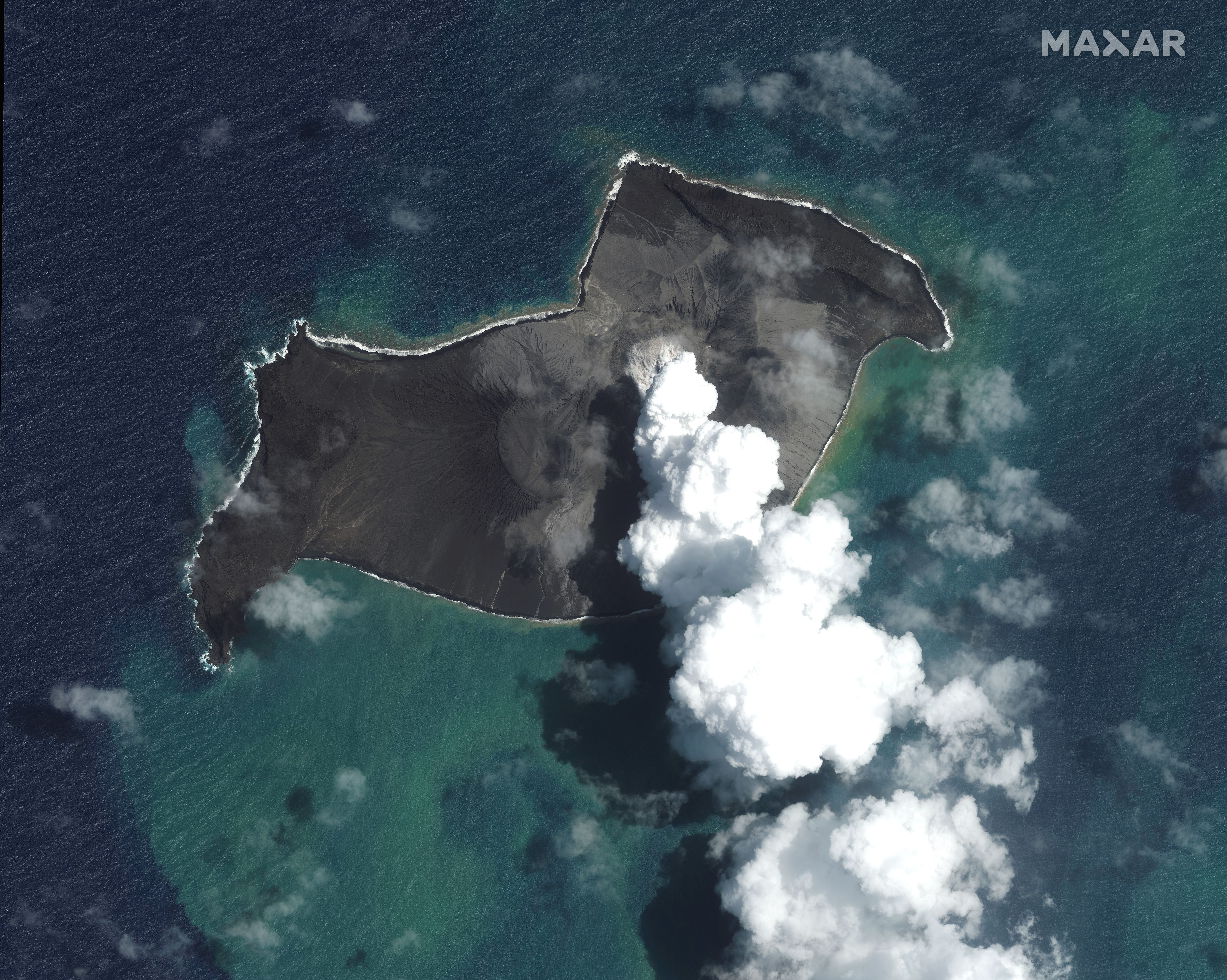

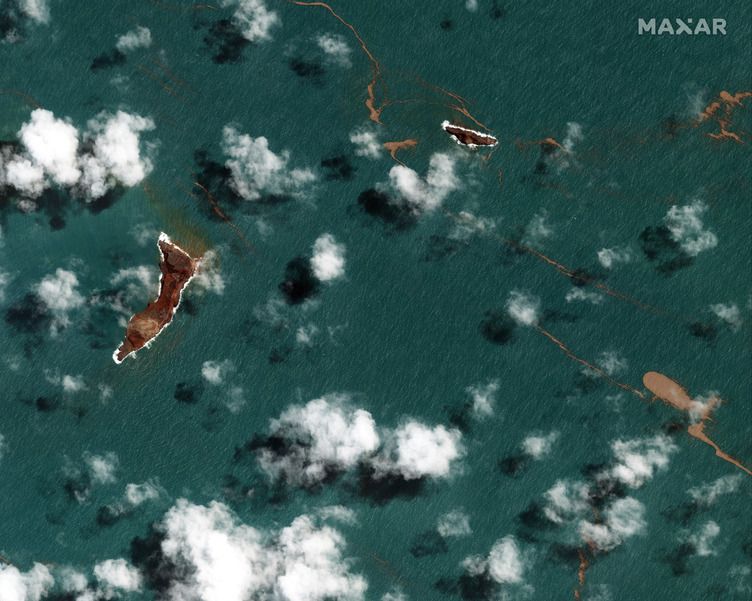

Powerful volcanic eruptions, such as the one that ripped apart the uninhabited Polynesian island of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai on Jan. 15, sometimes cause short-term cooling of the planet. But this won’t be the case of the recent mega-eruption, in spite of the fact that it spewed volcanic ash into record altitudes of more than 25 miles (40 kilometers).

The new study confirms previous estimates, stating that the cooling effect of Hunga Tonga could range from just 0.014 degrees Fahrenheit (0.004 degrees Celsius) in the northern hemisphere and up to 0.018 degrees F (0.01 degrees C) in the southern hemisphere, which is even less than some of the previous estimates expected.

Related: How satellites have revolutionized the study of volcanoes

How much a volcanic eruption cools down climate depends on the amount of sulfur dioxide in the volcanic it cloud generates. Sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere forms aerosol particles, which deflect sunlight, thus decreasing the amount of energy that enters the Earth’s system. For example, the 1991 explosive eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philipines produced a cooling of about 1.1 degree F (0.6 degree C) that lasted for nearly two years.

But the ash spewed into the air by Mount Pinatubo contained about 50 times as much sulfur dioxide as the cloud produced by Hunga Tonga.

The new analysis looked in detail at the spatial distribution of the volcanic aerosols in the atmosphere and the effects of the location of the volcano on the concentrations.

“Southern hemisphere volcanic eruption emissions are largely confined to circulating in the same hemisphere and the tropics,” Tianjun Zhou, a researcher at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said in a statement. “With less of an impact on the northern hemisphere. This in turn leads to a weaker global cooling than those of northern hemispheric and tropical volcanoes.”

The researchers cautioned, however, that this is an interim assessment based on new modeling that took into account the latitude at which the sulfate aerosols were released. A further challenge to making this model was the patchy historical data, as few southern volcanic eruptions of similar magnitude are in the historical record.

In the model, the researchers used 70 selected volcanic eruptions over the past millennium and tracked the global mean surface temperature response for the period of one year after the eruptions. They also double-checked their analysis with six well-recorded, large tropical eruptions (like 1991’s Mount Pinatubo) to see if their predictions matched reality, and found the model worked in those cases.

The study was published in the journal Advances in Atmospheric Sciences on Wednesday (March 1).

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.